Let’s take a moment to think about the way we live today. If you own a smartphone, the likelihood is that you will find yourself engaged in many different conversations every day. With just a few taps on a screen, you can confirm a meeting, sign a petition, find out the ingredients for baba ganouj, then buy them online − all while sitting down to lunch with friends at a restaurant table you booked via your favourite app.

These innovations are so fully a part our busy, modern lives that it is almost impossible to imagine a world in which communication was not immediate, where instead of sending a WhatsApp message to a relative in a faraway country, you had to put pen to paper, send the letter on a long and uncertain journey, then wait months for a reply.

Now, let us imagine the city of Damascus, some time in the 18th century. Its bazaar is buzzing with the voices of people who have come to buy goods, both imported and local. The smell of traditional soap fills the air, competing with the more pronounced aromas of cinnamon and black pepper that are on offer in huge piles in the front of many shops. As you walk down the narrow alleys, it is impossible to resist touching a pile of brightly coloured silk that is on display.

Outside that shop is an affluent merchant, whose conversational skills are as sweet as his negotiating ones are ruthless. How else would he have become the owner of six shops in this bazaar and two in the adjacent one? That takes a highly developed set of what we now call people skills.

In the late 18th century, this trader would most likely have sent one of his sons to Europe, on the other end of a trade route, perhaps somewhere like Marseille. The young man would have landed in the port city after a long voyage aboard a ship from Alexandria to be greeted by his father’s trading partner, a Christian man who had once owned shops in the same bazaar before selling them and moving to France.

On quiet nights, after work, the young man would write letters to his father under the light of a Quinquet oil lamp. In them, he would give detailed accounts of his new life. What most struck him was how little his French clients bargained before making their purchases from him. He felt strange selling his wares without the lengthy and passionate exchanges that always went before payment at home. He would also describe the clothes and manners of the French people, letting his father know that he was appreciating their culture, but not forgetting his own.

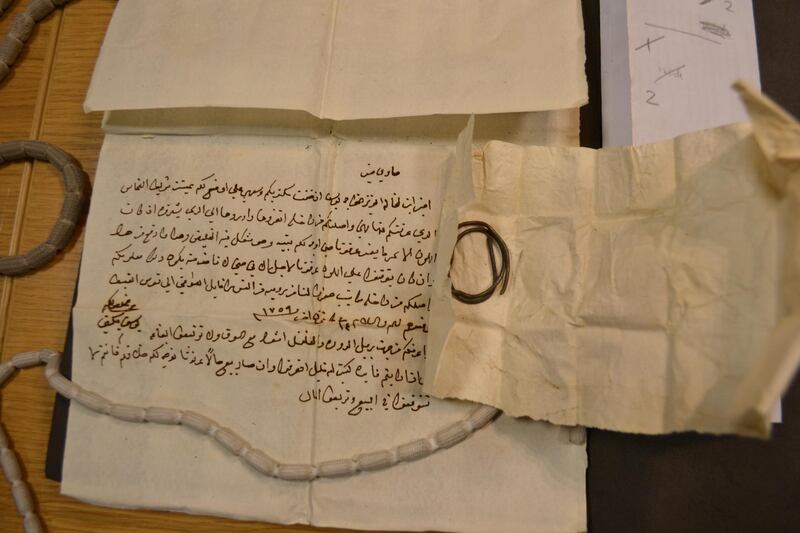

This young man’s missives are works of my imagination, but many similar ones are today being delicately opened and studied at the National Archives in London, where the Prize Papers − a collection of letters taken from ships captured by the British navy or privateer vessels − are stored. The papers cover the period between 1652 to 1815. At this time, it was common for ships to carry international correspondence along with their cargo. Most of the letters were seized still in their mailbags and many of them remain unopened.

The collection, which is now being digitised in a project by the National Archives and the University of Oldenburg in Germany, contains 160,000 private letters. They are written in 19 different languages and sent from countries all around the world – they include a personal letter from a Catholic priest in Lima, Peru, to his mother and fascinating insights to the everyday experiences of people living through the American revolutionary war and the Napoleonic conflicts.

But it is the Arabic letters that we are considering here. The number of messages to and from Arab merchants around the world contained in the Prize Papers is as yet unknown, but there are many. It may seem like a miracle that these fragile sheets of paper have survived so long, some even with their original wax seals intact. However, the fact that they were written in a language that most English naval personnel could not understand may have helped keep them in such pristine condition. Considered illegible, they were left in bundles and locked away for centuries.

This treasure trove of correspondence offers invaluable first-hand observations from Arab merchants on both sides of the Mediterranean as far back as three centuries ago. Their words − although many are arcane and hard to decipher, even for scholars of the Arabic language − show that it was primarily Christian and Jewish Syrian merchants who established outposts of their businesses in Europe. Cities such as Damascus and Aleppo were renowned for luxury items such as soap and embroidered textiles, but were also important staging posts for traders moving merchandise between Asia and Europe. Syria was a meeting point for East and the West, a place where goods were exchanged for cash or items of trade, then moved from caravan to ship; languages mixed, ideas were spread, cuisines and fashions blended.

Throughout the 19th century, while the sons of well-to-do merchants learned the languages and manners of countries such as Britain, France and Italy, European Christian missions founded schools in the biggest cities in the Levant − an area roughly encompassing today’s Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan. The presence of these institutions contributed greatly to the cultural fabric of the region, especially in trading cities such as Damascus, where European influence could be seen in the architecture and in the way people dressed.

This much we already know, but there is so much more to learn from these letters, sent but never received. They were written at a time of extraordinary events: the Anglo-Dutch wars, the industrial revolution and the gradual decline of the Ottoman empire. They reveal complex networks of international commerce but, most of all, they open a window to the intimate connections that existed between family members living oceans apart.

Next time we send a text to a loved one or business associate overseas, we should remember that we are following in the footsteps of people who wrote long letters that are only just being read. The attention now being paid to them offers the world a wealth of alternative narratives and a new and visceral connection with history.

Now, imagine a researcher carefully unfolding one of the Prize Papers today. You can almost hear the voice of a young man in Marseille: “My beloved father, these people have very strange manners. Today a lady bought 10 lengths of fine Damascus brocade without once asking me to reduce my price. She paid, ordered it to be wrapped and delivered to her home, then simply walked out, leaving her embroidered handkerchief on the counter.”

Tamara Alrifai is a Syrian columnist and human rights advocate living in Cairo