I started working at the British Museum in London nearly 30 years ago, just in time to help with the opening of the John Addis Gallery of Islamic Art. It was the first time the museum had opened a substantial gallery devoted to the art of the Islamic world. Prince Shah Karim Al Hussaini, Aga Khan IV, attended its inauguration. It was a grand, very exciting affair and I was lucky to be a part of it.

Located on the north side of the building, the gallery was beautiful but small and focused solely on Islamic art. We had more objects that we wanted to show and more stories to tell so in 2014, we started thinking about expanding the gallery. When the Albukhary Foundation in Malaysia generously agreed to support a move out of the John Addis Gallery of Islamic Art and fund a refurbishment of two rooms on the first floor of the museum, we couldn't believe our luck.

These rooms had once housed medieval European collections but had been closed for some time. When they were cleared, it became obvious there was a lot of work to do. The museum embarked on a massive renovation, working first with HOK architects, who shored up the structure of the building, and then with architects and exhibition designers Stanton Williams. The abandoned rooms were transformed into something absolutely magnificent; the original mouldings and the beautiful high ceilings were restored, providing an immaculate shell for what we had planned for the Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World, which opened to the public last month.

Back in 2014, it was left to me and the other five curators to figure out what objects from the British Museum's collection to display and then, working with the designers, exactly how to put them on show. That was not an easy task.

We conducted a lot of focus groups to find out what our audience wanted and, as I learned, it’s a science. The overriding message was that the old gallery concentrated too much on art. The focus groups were saying: “Tell us more about the people.”

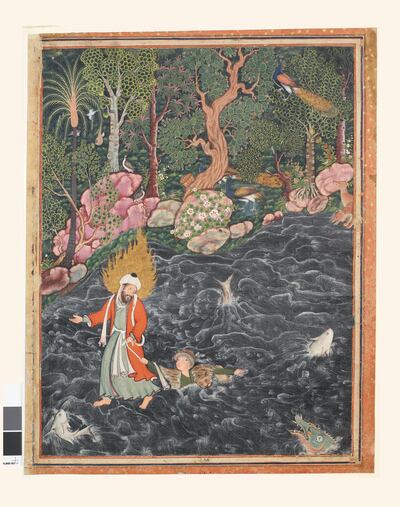

We wanted to create a gallery that brought to life the culture of the Islamic world, not just through art but everyday objects as well. There is a perception that the Islamic world is the Middle East but it is important to realise it is not just one region. It is a series of interconnected nations and continents, starting from the furthest point west in Nigeria, Africa, and stretching right across to south-east Asia. The thing that ties these regions together is the fact that Islam is the predominant religion but we also wanted to show there were people of other faiths inhabiting these regions: Christians, Jews, Hindus and Zoroastrians, among others. The arts also reflect massive upheavals across the Islamic world, such as the invasions of the Mongols from China or the Crusaders from Europe. We tried to give a nuanced story.

Bur rather than a mishmash, there is a strong structure. We present history complemented by a series of themes, such as writing and global trade. I like to think of it as a giant jigsaw puzzle. It is an attempt to tell lots of different stories, but we always start with the object. Rather than forcing a story on an object, we allow the object to tell the story.

We also brought in ethnography, which is quite unusual. Most museums with Islamic collections focus principally on art but we have costumes from Iran, Pakistan and Yemen, displayed in cases adjoining Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal court art. We have objects that belonged to sultans but we also have objects from everyday life. Every object, every story, is of equal importance. There is no hierarchy.

Our displays don’t just jump the barriers of social hierarchies, they provide a bridge between the ancient and modern worlds. For example, we have a display case titled “object histories”, highlighting how some of the objects in the museum have been collected over time. We have amulets acquired by the founder of the British Museum, Sir Hans Sloane, who died in 1753, which feature inscriptions he had translated into Latin by a Senegalese slave. Then in the same display case, we have some little boats made of bicycle mudguards and matchsticks by the contemporary Syrian artist Issam Kourbaj, which refer to the plight of modern-day Syrians forced to risk perilous voyages to flee their war-ravaged nation. It was important to us to display objects in a way that raised questions and encouraged debate.

There are so many wonderful objects, it is hard for me to share the highlights, let alone pick a favourite. I am extremely happy we were able to commission British artist Idris Khan – also responsible for the wonderful monument to the fallen heroes of the UAE in Wahat Al Karama in Abu Dhabi – to create a beautiful work for us. Its title is 21 Stones and it evokes the ritual during Hajj when people throw stones to cast out the devil. It consists of 21 works, each one made of stamped words emanating from a central dark core, in shades of blue and black. It is stunning and visitors love it.

My favourite objects are those with inscriptions. When you come into the gallery, on your left you will see what is perhaps my favourite inscription. It is the beginning of the phrase from the Quran, Bismillah al-rahman al-rahim – in the name of God, the merciful, the compassionate – in the most beautiful script you can imagine, its thick letters carved into a piece of stone originally from a cenotaph. It immediately signals to you the importance of the Arabic script to Islamic culture and is the perfect introduction to a journey into the Islamic world.

Venetia Porter is the curator of Islamic and contemporary Middle East for the British Museum and the lead curator behind the Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World