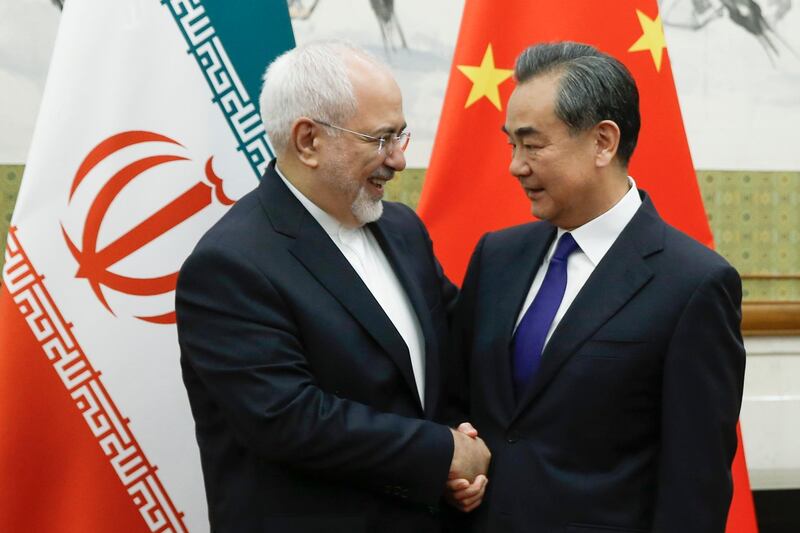

Iran has inserted itself in the ongoing stand-off between the US and China, with Tehran on the verge of signing a deal with Beijing. It has done so to achieve two goals. First, it aims to mitigate its economic isolation following the imposition of US-led sanctions, which continue to cripple the regime. Second, it seeks to appear as a player with significant heft in the Sino-American balance of power.

Iran and China are expected to strike an economic and military quasi-alliance in which the Tehran will offer its resources to Beijing's corporations and give it military and security concessions for a period of 25 years. The latter is said to be going forward despite opposition within Iran itself.

Iran is in a desperate quest for partners amid its growing isolation.

It has also been strengthening its relations with Turkey, especially in parts of the Arab region that serve as arenas for Turkish adventures, such as Syria, Iraq and more recently Libya. But Iran has faced complications elsewhere in the international arena. This is partly because sanctions make it difficult for Tehran to do business with Chinese, Russian and European companies and banks. It is also down to the fact that the geopolitical interests of the major powers run far beyond Iranian calculations – no matter how much Tehran likes to promote a different image of itself.

The dominant view of the Chinese-Iranian deal-making effort, among those I spoke with, is that it is more symbolic than strategic.

In veteran American diplomat Ryan Crocker's analysis, the agreement is overstated. "As I look at it, I don't see much in the way of concrete action [with the exception of economic aid]," he said. “The Trump administration's sanctions have created a real problem for Iran; their economy is in the shambles, and yes, China could step in and throw them a lifeline. If they do, it will have to be very carefully calculated and would have to think very carefully about how far they want to push particularly this administration."

Dr Irina Zvyagelskaya, who heads the Centre of the Middle East Studies at the Primakov National Research Institute of World Economy and International Relations in Russia, points to Beijing's increasing confidence while facing up to Washington. “I believe that China can really outlive any sanctions nowadays. It doesn't need Russia even, it can do it alone," she said. "This is very important because, as far as I understand, there is a nightmare in Washington that China and Russia unite against the United States."

Remarkably, Dr Zvyagelskaya dismisses the possibility of a Chinese-Russian-Iranian axis emerging in the Middle East, describing it as little more than a “phantom”. Speaking at the 11th e-policy circle of the Beirut Institute Summit in Abu Dhabi, she said: "[China and Russia] are allies. But at the same time, our interests are different – and it's obvious to everyone. So, when we are talking about China, let's talk about China, not 'plus Russia', because these are different sides."

US-China tensions have escalated in recent months, chiefly in areas of trade and security in the South China Sea. Leading officials in the Trump administration have been upping the ante against Beijing.

The US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has accused China of using intimidation tactics to undermine the littoral rights of south-east Asian countries. Last week, the Federal Bureau of Investigation director Christopher Wray claimed that the aim of the ruling Communist Party of China is for their country to replace the US as the world's only super power.

“The greatest long-term threat to our nation’s information and intellectual property, and to our economic vitality, is the counter-intelligence and economic espionage threat from China. It’s a threat to our economic security – and by extension, to our national security," Mr Wray said.

Tensions have escalated even further since China imposed a new national security law in Hong Kong, prompting US sanctions on banks and officials of the telecom giant Huawei. China has promised to respond with sanctions on US officials and entities.

I am reliably informed that Washington is prepared to take further punitive measures, including an embargo on Chinese banks, if Beijing implements some of the clauses reportedly present in its imminent deal with Tehran. Iran needs Chinese banks to carry out trade and financial transactions, but China is mindful that this might lead to an open confrontation with the US. It is therefore likely to stick to the agreement's symbolic aspects, for now.

Moreover, China has interests in the Gulf. It maintains strong ties with the UAE and Saudi Arabia, and there are few indications that it is willing to sacrifice them for the sake of upgrading relations with Tehran. It also does business with Israel, especially in key technology sectors. This alone is likely to present an obstacle in prospective ties with Lebanon.

Of course Beijing may not be averse to promoting its interests in Lebanon. And Iran-backed Lebanese militia Hezbollah, an integral part of the government in Beirut, may be keen for a Chinese-led bailout as the national economy suffers. But everyone knows the US is watching closely. China will therefore hold its cards close to its chest.

There are those in the international community who regard China’s rise is a fait accompli. Many even believe that the balance of power may be moving in Beijing's favour. But the countours of the imminent China-Iran deal have left some Arab experts concerned.

That China and Russia recently vetoed a UN resolution to extend a deal allowing aid delivery to rebel-held territories in Syria has given many Arabs pause. The former Libyan foreign minister Mohammed Dairi, for instance, told me: “It doesn't surprise me that China would seek to forge better relationship with Iran." He worries that China may even turn a blind eye to Iran’s activities in the Arab region, including in Libya, where Tehran's interests are converging with those of Ankara, as both countries look to deepen their presence in North Africa.

Libya could be an important theatre for China, too, given its economic influence in the rest of Africa. However, it is aware that Russia is a dominant player in the North African country.

For now, it seems focused on getting its foothold in Iran.

Raghida Dergham is the founder and executive chairwoman of the Beirut Institute