There are many reasons why the success of the Bosnian film Quo Vadis, Aida?, which chronicles the 1995 genocide in the town of Srebrenica, is remarkable.

The fact that a 46-year-old Bosnian woman with a multi-ethnic cast made a mark far into the upper echelons of Hollywood is groundbreaking. In an industry that usually rewards Borat, a serious feature about war doesn't seem probable. But Jasmila Zbanic, the director, who came of age during the siege of Sarajevo, has made a film about a massacre that some people still deny happened.

My wish is that Quo Vadis, Aida? will reach a wide audience – of those who were born long after 1995. If viewers who never heard of Srebrenica – or don't know where Bosnia is – watch the film, they will come away with a unique understanding of an ethno-nationalist war that occurred in Europe at the end of the 20th century.

It was a conflict that took human cruelty to horrific levels, with concentration camps, systematic rape, torture and starvation used as tools of war. It is one we must never forget so that we can prevent others like it from happening again.

As a reporter who worked there throughout the war, Bosnia is burned into my mind. But for most, Bosnia remains a distant and unknown country that is perhaps too complicated to comprehend. At Yale, I teach a seminar on human rights and modern conflicts. Bosnia is one of the wars we analyse. Yet many of my students do not know anything about Bosnia when they enter the class, something I find astounding, given their overall brilliance and breadth of knowledge.

Quo Vadis, Aida? could potentially change that. It has been nominated for best international film at the Oscars and the Baftas. If it wins and gets the attention it deserves, it means that this war – which was in many ways a template for future wars to come, including in Syria – will be lodged in collective memory. Remembering and acknowledging the horror is a small but vital step towards healing. Bosnia, 26 years after the war ended, is far from healed.

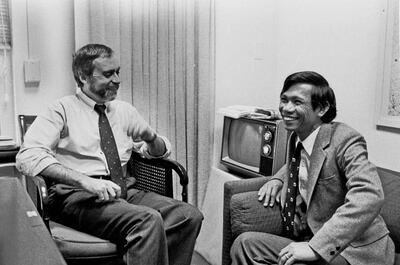

Films have the power to reach mass audiences in a way that books sometimes don't. Art can be forged not only from cultural or spiritual events, but also heinous moments in history. The Killing Fields, a 1984 British biographical drama, told the story of the horrendous years of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia in the late 1970s. By focusing on the relationship between an American journalist and his Cambodian interpreter, the narrative of male bonding against the backdrop of a brutal war became a universal story. Roland Joffe, the director, was able to draw a wider international audience and educate them about the resulting genocide that killed up to two million people.

The Killing Fields was widely acclaimed and did well at the box office. It received seven Oscar nominations and was awarded three, but it also drew the attention of many young people – myself included – who had no idea what the murderous Pol Pot's regime had done. Many years later, Angelina Jolie, who has an adopted Cambodian son, went on to direct a powerful film based on the memoirs of Cambodian-born American activist Loung Ung titled First they Killed my Father: a Daughter of Cambodia Remembers. It shows the Pol Pot years through the eyes of a young girl and was shown on Netflix – reaching more people than a cinema release would have reached.

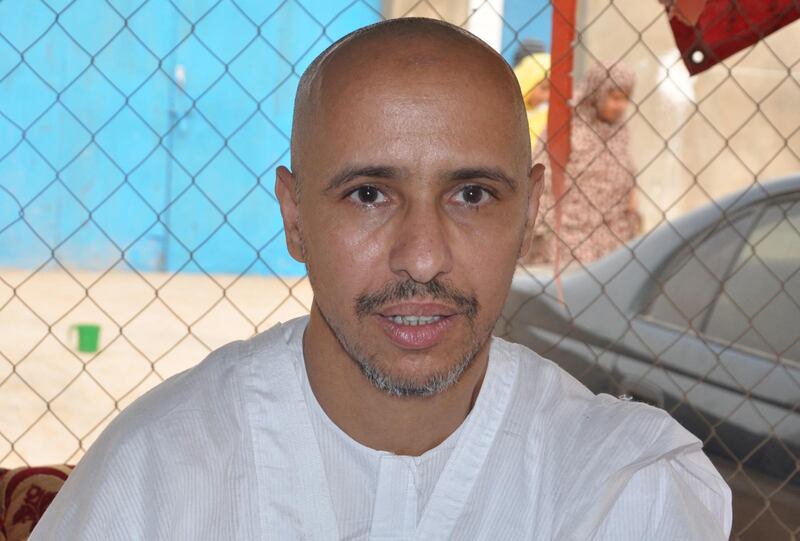

Another powerful film is The Mauritanian, starring Jody Foster. It is a recent release and will leave many appalled at the conditions and treatment of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay. The film is a true story recounting the journey of Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who was wrongly accused of terrorist acts following the September 11 attacks.

Slahi was held for 14 years inside the grim cells of Guantanamo without a charge, undergoing brutal physical and psychological torture at the hands of his American military handlers. Even after he was cleared of all charges by a federal court, he was held for another six years before he was released. Originally published as a book, Guantanamo Diary was largely redacted by the US government, but still described by The New York Times as a document of "immense emotional power and historical importance".

Slahi wrote the book in prison and it became a best seller. The film left me shaky and disturbed, making me go back to look at documents and research papers on Guantanamo. Although I was covered the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan at the time, I had missed Slahi’s story. The film, however, will never let me forget.

These are not easy films to digest and they keep you awake at night. Quo Vadis, Aida? was especially difficult film for me to watch. Like many who witnessed the atrocities there, I have immense shame and sorrow at the international community's abandonment of the people of Srebrenica.

Zbanic came of age during the siege of Sarajevo, a time when snipers aimed their guns at the knees and hearts of women and children, and when art and culture was destroyed. The National Library, for instance, went up in flames following an order given by a psychopathic Bosnian Serb Shakespearean scholar. Nonetheless, Zbanic survived and in some ways thrived. She attended the prestigious film academy and went on to make two important films, one about radicalisation and the other about a Serbian neighbourhood in Sarajevo. Her goal as a director is to leave an imprint of the terrible events of Srebrenica on the public memory. She also believes that this film will act as a sort of bridge for both Serbs and Muslims to begin a form of reconciliation and healing.

The film traces the three days that shamed the world from the fall of the city to the UN’s alleged complicity in the slaughter of 8,000 Muslim men and boys. I cried from the opening scenes until the end. I cried largely because I knew what was coming at the end, but also because Zbanic filmed so powerfully and so beautifully that she made those awful days in July, 1995 indelible. Now, no one can erase them.

It made me think of other films that captured history, aside from The Killing Fields, which had moved me and taught me more about a conflict. The post 9/11 wars in Iraq and Afghanistan brought many feature films, the best among them in my view being The Hurt Locker, about a demining expert suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Bradley Cooper also pumped himself up to play American Sniper, based on the life of a former Navy Seal sniper called Chris Kyle, considered the deadliest marksman in US military history.

But American Sniper perturbed me, and not in the way that Quo Vadis, Aida? did. Kyle did four tours in Iraq and was proud of his 255 kills. Directed by Clint Eastwood, the film was controversial, largely for the portrayal of the war in Iraq, but also because in his memoir, Kyle described killing as "fun" and something he "loved".

Ironically, and unfortunately, Kyle was murdered in Texas in 2013 by a veteran suffering from PTSD.

There was The Kite Runner and a spate of Osama bin Laden films, including one about his capture, Zero Dark Thirty. But these are action films, intended to reach a different audience.

Which is how Quo Vadis, Aida? is unique. It's not just an action movie aimed at teenage boys. By telling the story of Srebrenica through the eyes of a UN interpreter – who is also a mother and wife – Zbanic hopes people will learn about the genocide, so that it never happens again.

It is an educational tool and a vital mechanism to discuss genocide – not just in Bosnia, as Zbanic told me, but everywhere – so that people will learn never to make the same mistakes again.

Janine di Giovanni is a senior fellow at Yale’s Jackson Institute. Her next book, The Vanishing, about Christians in the Middle East, is out in the autumn of 2021