As students go back to school and start thinking about where to apply next, the British government has not been a good advertisement recently for its oldest and arguably most prestigious university, Oxford.

In the few weeks since Oxford alumnus Boris Johnson became prime minister, he has suspended parliament, reduced his majority in the house, been accused of trampling on democracy and possibly subverted the rule of law.

Mr Johnson is the latest in a long line of prime ministers to have graduated from Oxford; the 29th out of 56, in fact, including Robert Peel and William Gladstone in the 19th century, right through to Tony Blair, David Cameron and Theresa May. For some alumni, however, graduating from Britain's finest – Oxford has been ranked first in the annual Times Higher Education world rankings for the fourth year in a row – lends a certain amount of entitlement.

Behold, for example, Jacob Rees-Mogg, leader of the House of Commons and graduate of Trinity College, Oxford. He was pictured recently draped across the front benches during a debate on Brexit, in a manner described by one commentator as "waiting to be fed grapes". Then there is the Bullingdon Club, the infamous all-male drinking circle made notorious by its recruits' rowdy behaviour. The current prime minister, Mr Cameron and former chancellor of the exchequer George Osborne have all been members. It seems the so-called elite is doing everything it can to live down to expectations.

As an Oxford graduate myself, such behaviour makes my skin crawl and leaves me asking whether establishments like Oxford have anything to say in the 21st century world?

Spoiler alert: yes they do, but it is going to require a painful transition in a rapidly changing world, one where simply belonging to a historic institution is not enough, and where people are less enamoured of the idea of (predominantly white) upper-class superiority that held for centuries.

Oxford, like many other elite institutions, has been making important and laudable efforts in recent years to respond accordingly, starting with attempting to recruit a more diverse intake of students. As a Muslim woman of colour, from a working-class, immigrant background, I was definitely one of those who ticked the diversity box when I took up my place 20 years ago as an undergraduate studying psychology and philosophy.

Statistics also show change is happening. For example, year on year the number of students from state schools has risen from 56.3 per cent in 2014 to 60.5 per cent last year, according to Oxford University figures.

I returned last weekend for the first time in years for a reunion. I felt 18 years old again, spending time with my peers in a bubble of joy, delight and nostalgia. Oxford was everything it had always been. Its golden stone buildings still gleamed in the sunshine. The shadows in its cloisters whispered romance. Its vast libraries still held the knowledge of centuries.

But in a way, that perfectly preserved nature is also part of the problem. At the reunion, I compared notes with others who, like me, considered themselves outsider-insiders. The Oxford experience had given us many things: access to smart minds, unparalleled resources, a tutorial system that trained us for the toughest work meetings, the relentless honing of our ideas, a peer group which put us with insightful, inspiring people who remained friends for life and who – whether we liked it or not – were likely to provide connections and open doors.

Those are huge advantages. But for many students, that is no longer enough. Course content and cultural life are now make-or-break factors in decision-making about where to study, along with a university’s reputation.

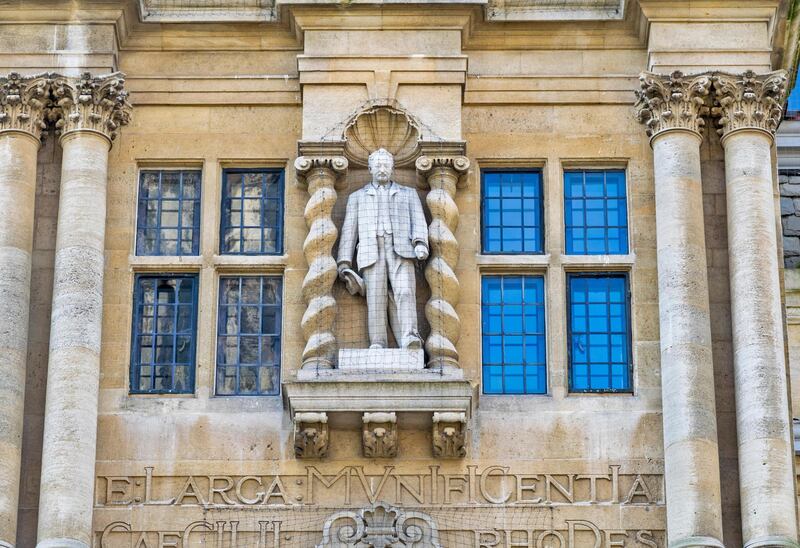

Take one recent controversy involving Oxford, which sparked a painful self-examination of its own place in the history of the British empire and establishment. In 2015 a worldwide campaign called "Rhodes must fall" began in Cape Town and spread to Oxford, prompting students to call for the removal of memorials in honour of Cecil Rhodes, the 19th century prime minister of Cape Colony, now South Africa. A former student at Oriel College, Oxford, he was an advocate of racial segregation, thought Anglo-Saxons were "the first race in the world" and described native Africans as "barbaric". Despite opposition, Oxford University decided to keep his statue, arguing that more than $100 million in sponsorship depended on it.

But how Oxford handles issue such as this is not just a matter of funding and institutional survival; it also sends a message to students and wider society about how it sees itself and its role. How it frames its own history – when so much of society is re-evaluating issues such as equality, the legacy of colonialism or women’s rights – speaks louder to students than anything else. They are looking for an inclusive place that will prepare them for the kind of world they want to be a part of, not a past they don’t want to preserve. This is the huge cultural shift that has happened over the past half-century and which has accelerated in recent years.

The big picture we are all working towards is a society where everyone, irrespective of their background, has equal access to social, economic and political opportunities. To do this, we need to make institutions such as Oxford representative as well as reflective of the contemporary world.

Oxford has much to offer and if I was to have my time again, I’d still apply, for the experience. But I’d also do it because the only way to challenge the status quo is by being there to instigate change in the first place.

Shelina Janmohamed is the author of Love in a Headscarf and Generation M: Young Muslims Changing the World