“I reiterate that the government is fully prepared to co-operate with the ICC to facilitate access to those accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity.” So declared Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok on August 22, 2020.

Some surely are asking: haven’t we have heard this type of talk from Sudanese officials before? Yes, we have. What we have not seen are any trials of any perpetrators involved in atrocities in Darfur – or the rest of Sudan. Will this latest round of rhetorical commitment to justice translate into actual accountability?

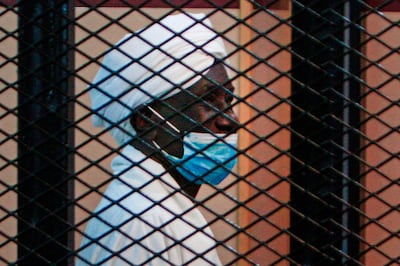

Not long after former Sudanese President Omar Al Bashir’s unceremonious fall from power in April 2019, officials in the country stated their interest in Al Bashir “appearing” before the ICC. The announcement was met with a feverish reaction. A decade after the ICC issued warrants for his arrest, would Al Bashir finally find himself before judges in The Hague?

The answer, we now know, was no. In fact, Sudan’s new rulers hadn’t said the country’s former head of state would be sent to the ICC. Rather, they appeared interested in having the ICC put Al Bashir – and others wanted for atrocities in Darfur – on trial in Sudan itself.

This is also how Mr Hamdok’s remarks should be understood. He did not say that Sudan was prepared to ship off defendants to the ICC, but that Sudan is now ready to co-operate with the court to facilitate “access” to those accused. Some, like Al Bashir and former ministers Ahmad Harun and Abdel Rahim Mohammed Hussein, who are also implicated in the commission of atrocities in Darfur, are currently under arrest in Sudan.

So, what does Mr Hamdok’s commitment to cooperate with the ICC mean? Is it an empty gesture?

The short answer is no. This is the first time that someone as senior as the Prime Minister has spoken out in favour of co-operating with the ICC. His comments also come in the wake of protests in which the subject of ICC justice has gained some traction, as well as the recent revision of laws that precluded Sudanese authorities from co-operating with the ICC.

As one human rights advocate recently observed, the reforms are “a welcome signal that Sudan’s leaders take seriously their public promises to co-operate with the court on outstanding arrest warrants”. The regular and repeated declarations of support for the ICC from within the Sudanese government also make it harder to backtrack on their pledge to ensure those targeted by the court for atrocities in Darfur will be prosecuted.

What justice for events in Darfur might look like remains murky. The same options on the table exist now as they did when the government first suggested it would work with the ICC. The court's Prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, recently stated that she is not aware of the government's plans. She has spoken of difficulties in her interactions with interlocutors in Sudan due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the inability of her staff to visit Sudan.

So far, authorities have not tipped their hand as to whether they would surrender Al Bashir, Harun or Hussein to The Hague if the court is unwilling or unable to hold proceedings on Sudanese territory. Nor have they indicated any interest in investigating and prosecuting those responsible for international crimes in Darfur themselves; Al Bashir has been tried in Sudan, but only for corruption and related crimes.

To be sure, after decades of Al Bashir’s rule and Sudan’s designation as a pariah state, Khartoum wants the benefits that international rehabilitation can bring. Co-operating with the ICC would appear to be part an effort to look like a member of the international community in good standing. But the desire to “come in from the cold” may also be a reason why Sudan has chosen a one-foot-in-one-foot-out approach to the ICC: committing to co-operation, but not spelling out what that would look like.

Governing authorities may want to leverage their co-operation for other benefits – including on financial, diplomatic, and trade matters – from states that would like to see Al Bashir prosecuted by the court. Sceptics might also suggest that while Sudan’s rulers are interested in co-operating with the ICC, they will only do so if their leadership is protected from investigation and prosecution by the court.

Despite the tectonic political changes in Khartoum and ongoing negotiations with rebel forces, which included an agreement to “hand over” Al Bashir to the ICC, mass violence in Darfur continues, with civilians facing the brunt.

Parallel to demands for ICC justice, Sudanese protestors have also demanded justice for the deaths of at least 120 demonstrators during the popular uprising that ousted Al Bashir from power. Authorities have promised accountability for the killings as well as alleged sexual assaults and rapes committed by security forces. But some of those same authorities are themselves implicated in atrocities. Awad Ibn Auf, one of Sudan’s coup leaders, for example, has been sanctioned by the United States and “helped to stand up the infamous proxy militia force known as the Janjaweed, who brutalised the Darfuri population”.

Ultimately, what the ICC needs most is co-operation from Sudanese authorities. It remains unclear whether ICC prosecutors are ready for Al Bashir to show up in The Hague. It has been an open secret for many years that prosecutors were not prepared for him to be handed over to be tried for genocide, a notorious difficult crime to prove in court. Of course, that was before he was overthrown and before ICC investigators had access to evidence in Darfur and the rest of Sudan.

Now, with Sudan’s co-operation and access to potential defendants, ICC investigators and prosecutors could encourage some of those languishing in jail to testify against Al Bashir or plead guilty while supplying the court with invaluable evidence and testimony. That would prove a coup of its own for prosecutors.

It might thus be wrong to suggest that Khartoum is dithering on justice only out of a sense of self-interest. Al Bashir’s prosecution would be the ICC’s biggest, most difficult and most dramatic to date – by far. The court’s prosecutors might be quite happy, then, for the wheels of justice to grind slowly but surely. It gives them ample opportunity to prepare for Al Bashir’s trial – wherever it may take place.

Mark Kersten is an expert in international law and a consultant at the Wayamo Foundation