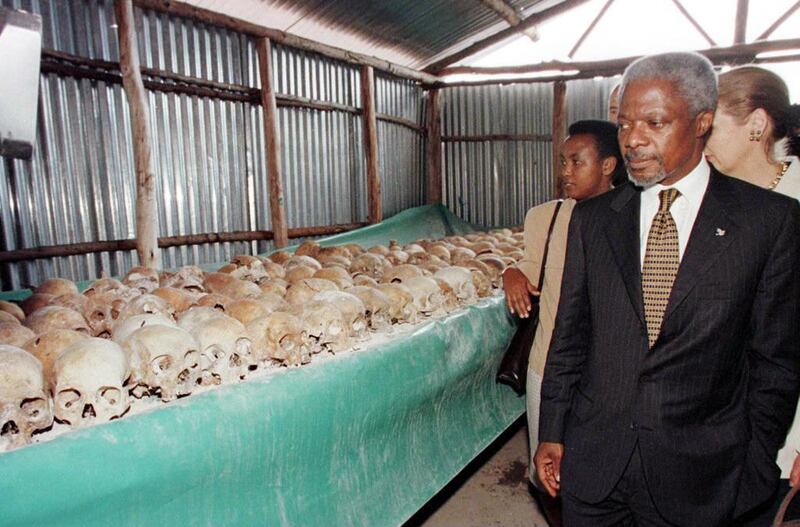

On March 26, 2004, UN secretary-general Kofi Annan rose to give the opening speech at the Memorial Conference on the Rwanda Genocide. What followed amounted to a mea culpa of historic proportions, on behalf of himself and the organisation he led.

A decade earlier, more than 800,000 Tutsi men, women and children had been slaughtered in a 100-day genocidal frenzy by members of Rwanda’s Hutu majority, while a small, inadequately equipped and poorly mandated UN peacekeeping force could only look on helplessly.

At the time Annan – who died this month – was in charge of UN peacekeeping operations. The genocide, as he conceded at the memorial conference in New York, “should never, ever have happened”. The international community “could have stopped most of the killing ... but the political will was not there, nor were the troops”.

As the man at the top, Annan always knew he bore ultimate responsibility for the failings of the UN on his watch, but the role of secretary-general, which he held from 1997 to 2006, was and remains a poisoned chalice. The organisation's limitations and the multiple failings over the past 70 years to which they have led, were set in stone at the UN's foundation.

The UN was the successor to the League of Nations, a body set up in the aftermath of the First World War to prevent disputes from ever again escalating into such catastrophic conflict. Hampered from the outset by the refusal of America and Russia to take part, it failed miserably, as the outbreak of the Second World War testified.

Afterwards the world tried again to create an independent organisation dedicated to preserving peace and in June 1945, 50 nations, led by the US, Great Britain and the USSR, gathered in San Francisco to sign the UN Charter. It opened with these stirring words: “We the peoples of the United Nations determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind ...”.

But once again the seeds of failure, cultivated by self-interest, were sown from the outset.

Although the UN now has 193 member states, only a handful have any real influence when it comes to taking serious action. Time and time again the organisation's good intentions – and those of the thousands of doubtless well-meaning individuals who work for it – have been sabotaged from within by an inner circle of the five permanent members of its 15-strong Security Council, any one of which can veto any proposal. That reality renders the UN frequently impotent and hostage to the agendas of powerful nations.

With no independent army, the organisation has no way of imposing its well-meant will on the world. If America – or China, France, Russia or the UK – doesn't like something, it doesn't happen.

It is true that since 1948 the UN has helped to end conflicts and bring about reconciliation in dozens of countries, notably Cambodia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mozambique, Namibia and Tajikistan, but its successful peacekeeping missions have tended to be in parts of the world where none of the major powers have a vested interest in a particular outcome.

The Security Council veto has been used more than 200 times since 1948. Russia has deployed it eight times so far in the Syrian conflict alone and the US has blocked 43 resolutions pertaining to Israel. One of the most recent was December’s veto of a resolution opposing President Donald Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. The latest was in June, when the US blocked a Kuwait-led call for international protection for Palestinians.

But the dead hand of the veto isn’t the UN’s only problem. Over the years the organisation has grown flabby – its New York-based secretariat is now 38,000 strong – and increasingly inflexible. The consequences of this institutionalised intransigence were apparent in Rwanda over three months in 1994.

Six months after Annan's Rwanda Memorial Conference speech in 2004, Lt-Gen Romeo Dallaire of the Canadian army, who had commanded the UN force in Rwanda and had failed to win the organisation's support for a more proactive stance, published his book Shake Hands With The Devil. It was a searing indictment of international apathy, an "inept [and] inflexible" UN Security Council mandate, the "penny-pinching financial management of the mission" and the throttling effect of UN red tape which, in Dallaire's view, had cost hundreds of thousands of lives in Rwanda.

Annan's death this month at the age of 80 has been greeted with the expected outpouring of glowing tributes to a man whom most commentators and contemporaries agree was a "lifelong champion of peace, justice and equality". Even Dallaire conceded in his book that Annan was "decent [and] dedicated to the founding principles of the UN".

But frank criticism has accompanied praise following the death of the man who, in 2001, shared the Nobel Peace Prize with the organisation he led, awarded for "their work for a better organised and more peaceful world". As The Atlantic's obituary put it, "Annan's legacy will be defined as much by his failures ... as by his many successes".

Those failures, many of which are associated with grim death tolls, should not be laid solely at Annan’s door.

In 1996, a year after the Rwanda disaster, 8,000 Bosnian Muslims were massacred by Serbian troops at Srebrenica, in a UN so-called “safe area”. Annan admitted later that, once again, “great nations [had] failed to respond adequately [and] there should have been stronger military forces in place”. The UN, he said, had “made serious errors of judgement, rooted in a philosophy of impartiality and non-violence ... unsuited to the conflict in Bosnia."

Institutional lessons had not, it seemed, been learnt from the Rwandan genocide which, in Annan’s words, had raised “fundamental questions about the authority of the Security Council [and] the effectiveness of United Nations peacekeeping”.

Those same questions have been raised repeatedly, and never more so than in the wake of the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq.

By sombre coincidence, Annan's death on Saturday came on the eve of the 15th anniversary of the August 2003 suicide bombing of the UN headquarters, housed in Baghdad's Canal Hotel, carried out at the height of the murderous insurgency unleashed by the invasion.

At a memorial service in New York a month later, held for the 22 killed in that attack, Annan expressed his shock that the UN had been targeted even though it was in Iraq “solely ... to help the Iraqi people build a better future”.

But those who gave their lives serving under the blue flag in Baghdad did so as a direct consequence of the UN’s failure to prevent the invasion in the first place.

America and Great Britain had insisted the invasion was an act of self-defence, prompted by supposed Iraqi plans to build weapons of mass destruction, and thus sanctioned under the UN charter. But it was not, as Annan himself later admitted. Article 51 of the charter gives all states the right of self-defence only if attacked. To extend that right to allow pre-emptive action represented “a fundamental challenge to the principles on which, however imperfectly, world peace and stability have rested for the last 58 years”.

Too little, too late. The UN had proved powerless to prevent the tragedy and it would be September 2004 before Annan finally conceded, in a BBC interview, that the war had been illegal.

Nowhere is the inability of an institutionally deadlocked UN to act effectively more starkly illustrated than in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The UN currently has international peacekeepers operating in 14 countries. One of those missions is UNTSO, the United Nations Truce Supervision Organisation, designed to “bring stability in the Middle East”.

UNTSO was the UN’s very first peacekeeping operation, established in May 1948. The fact that it is still going, ineffectually, 70 years later, is the single most damning indictment of the hamstrung UN’s inability to live up to its founding ambition to end the world’s untold sorrow.