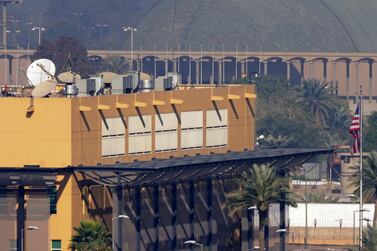

The US is exploring options for shuttering its embassy in Baghdad and moving critical functions to a consulate in Erbil, indicating that the Kurdish region may be more capable of protecting its American partners on the ground than is the federal government.

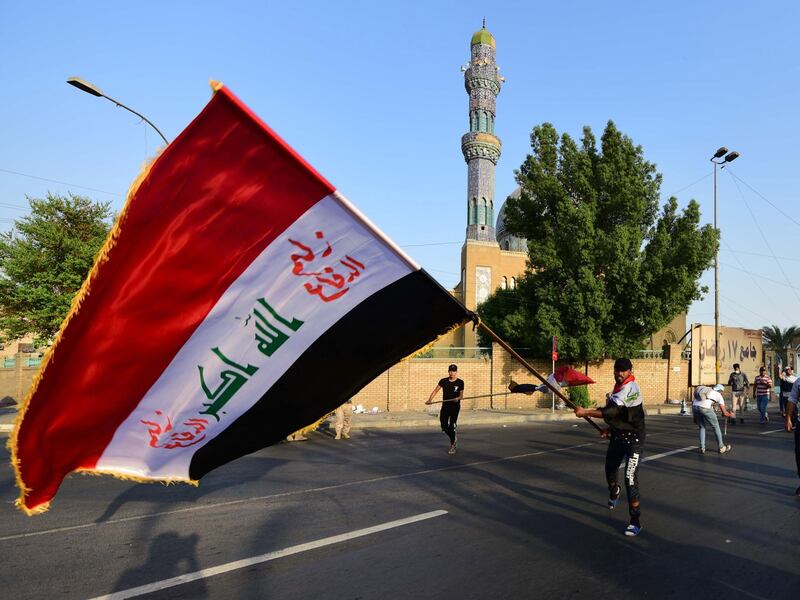

The embassy in Baghdad has been under attack from Iranian-backed rogue militias on a near-weekly basis for months. Since the killing of Iranian commander Qassem Suleimani in a US strike near Baghdad airport in January, groups that are deemed "outlaws" by the Iraqi government have constantly threatened American targets, among them diplomats and troops stationed in the country. Suleimani had been the head of Al Quds force, an elite branch of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which co-ordinates overseas operations conducted by Tehran's proxies.

The message to close the embassy – delivered by Mike Pompeo, the US Secretary of State, and Matthew Tueller, the US ambassador to Iraq, to President Barham Salih, Prime Minister Mustafa Al Kadhimi and Foreign Minister Fuad Hussein all within a week – is causing both panic and jubilation in Baghdad. America has friends in Iraq who are trying to manage the realpolitik of Baghdad, running a country that is dependent on two adversaries. They now face an ultimatum after two years of increasingly urgent requests from Washington to control armed groups in their own capital.

Discussion of the embassy's closure serves three purposes for the Trump administration.

First, it signals to politicians in Baghdad who have enjoyed American goodwill that they are expected to control the militias that are nominally part of their security services, or the goodwill will end. Key political figures such as President Salih are advocates of sound US-Iraq relations and America's role in building their country’s defences and economy. But they have felt unable to act in ways that safeguard American presence because of pressure from political factions aligned with Iran.

Second, it allows Prime Minister Al Kadhimi to point to a tangible consequence of the actions of these rogue militias. If they continue to attack the US presence, it will withdraw, taking with it critical assistance funding, advisers and technical know-how, which is untenable to much of Iraq's professional class. Closure of the embassy and all that it entails will also make Iraq a much more permissive space for ISIS, which even Iraqis aligned with Iran do not wish to see again.

Third, the closure removes from Iraq the likely American targets for Iranian retaliation whenever the US strikes Tehran-aligned groups. If its proxies continue to direct rocket attacks at the embassy with the purpose of pressuring the US to withdraw its diplomatic presence from Iraq, Iran is knowingly offering Iraqi lives to pay for it.

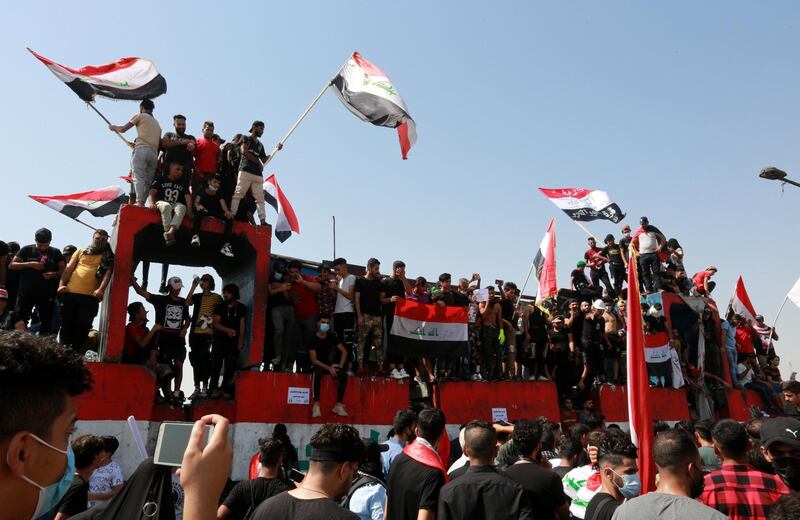

If the US closes up shop and goes home, claiming a win will put Iran in the position of having to admit its role in controlling the Popular Mobilisation Forces – an umbrella group of mostly Tehran-backed militias that are officially part of the Iraqi state's security apparatus but are also believed to be behind a deadly crackdown on peaceful protesters in recent months. It would amount to a change in official narrative. It would be an admission that Iran's foreign policy violates Iraq’s sovereignty. At the same time, President Donald Trump will claim a win against these groups, notably, without starting a war.

After the November 3 presidential election, a US administration with a new or renewed mandate and its accompanying leverage will then begin discussions about reopening the embassy.

For the Iraqi government, this is not altogether a bad time for the US ultimatum to be issued. While the frequency of attacks by Iran’s proxies on US interests is rising, the severity of each attack is scaled back, according to the US Department of Defence. This indicates that Iran wishes to press the case for America's withdrawal but does not seek to escalate the Baghdad-based tensions into a broader conflict – at least not until November 4. President Salih and Prime Minister Al Kadhimi can realistically make the request that Tehran decrease the volume of militia attacks for the next six weeks in order to deny the US the justification for wiping out militia headquarters and arsenals that Iran may later wish it had.

Kirsten Fontenrose is director of the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative and an adviser to Kuwaiti think tank Reconnaissance Research. She previously served as senior director for Gulf affairs at the National Security Council in the Trump administration