Six years ago this week, members of the vicious extremist group Boko Haram set out to finish what they had started. In a brutal siege, they massacred 51 people in the village of Chibok in north-eastern Nigeria, many of them parents of 276 schoolgirls the militants had violently abducted three months earlier.

It was an added blow, and a security failure, just as the international community was loudly demanding the girls’ release. It contributed to the election of Muhammadu Buhari, 10 months later, on a key promise: to defeat the insurgents and restore order.

Today, 112 Chibok girls are still missing and Boko Haram continues its murderous campaign. Other violent conflicts, involving bandits, herders and farmers, continue unabated. Nigeria is facing its worst recession in 40 years, exacerbated by the drastic collapse of global oil prices. And Mr Buhari, 77, looks short of ideas, after spending months of his first term in London seeking medical treatment for a mystery ailment.

The Nigerian President was so ill that he famously reassured the public in a speech that he had not died and been replaced by a lookalike. What hope then, for Africa’s richest nation and biggest oil producer, to handle the lasting impact of the global coronavirus pandemic?

In a 2017 analysis of Nigeria’s ability to respond to public health emergencies, the World Health Organisation gave the country 1.9 out of five for prevention, 2.6 for detection and 1.5 for response.

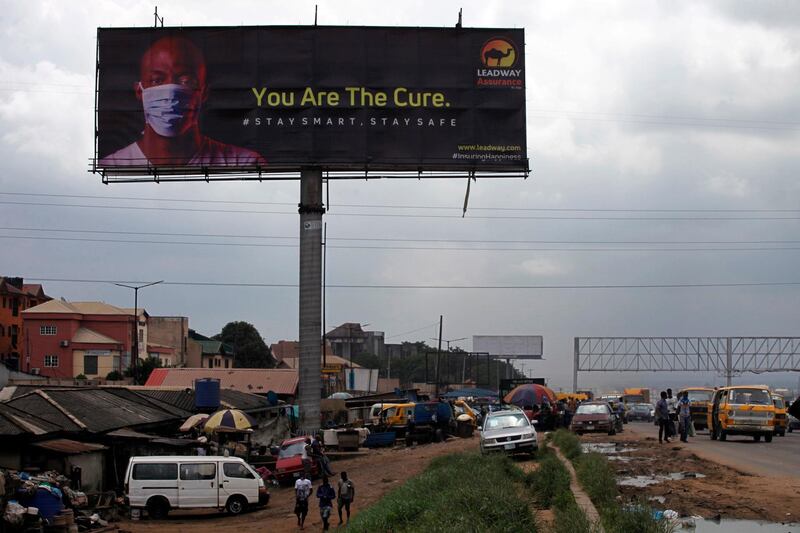

Four months after the pandemic hit Nigeria, those marks seem prescient. Today, Nigeria is administering 0.9 tests per 1,000 people, compared to 36 in South Africa and 11 in Ghana. It also has a mere 450 ventilators for a population of 200 million.

Cases have remained fairly low in Nigeria, as they have across Africa, but a devastating outbreak is not out of the question. With 35,000 cases, it is sub-Saharan Africa’s second worst-hit nation. And the data could be skewed. In late April, around 1,000 people died over a short period in Kano state, but the government has still not confirmed a coronavirus link.

As ever, Abuja’s response is well-intentioned but does not go far enough. Loans to poor families by the central bank, for instance, require collateral and interest to be paid, ruling out many of those most in need. Meanwhile, the Economic Stimulus Bill – the cornerstone of Nigeria’s economic rescue plan – ignores the informal sector, which hires 90 per cent of Nigeria’s workforce and underpins 65 per cent of economic output.

The upshot is loans and debt, including $3.4 billion from the IMF and $8bn in total from the stock market, World Bank and African Development Bank.

Given the oil price crash in April (when crude fell to negative $40 a barrel), corruption, decaying infrastructure and predictions that Nigeria’s GDP will decline by 5.4 per cent this year, one wonders how Africa’s economic powerhouse can stay afloat.

For many Nigerians, economic hardship is nothing new. The country is already home to more people in extreme poverty than any other – including second-placed India, which has 1.3bn people. And every year, tens of thousands of young Nigerians pitch up in Lagos, the economic capital, to hustle a better life for themselves and their families. They have long deserved better from.

Despite it all, the economic situation pales in comparison to chronic security challenges.

The Boko Haram insurgency, 11 years old, steals the headlines having killed tens of thousands and displaced millions into Chad, Niger and Cameroon. Despite some successes, the relentless campaign has sunk morale in Nigeria's fragile military, causing soldiers to withdraw into fortified towns in the north-east and leave main roads and smaller towns at the mercy of the militants.

Just last month, a string of attacks by Boko Haram and its splinter group, Islamic State West Africa Province, killed hundreds in Borno state. A single attack left 81 dead.

But other less talked about conflicts continue to exact a toll on ordinary Nigerians. In the country’s north-west, armed groups and gangs of bandits, operating out of forested camps, have killed hundreds of civilians in recent months in the states of Katsina and Zamfara.

Despite ground and air operations by the Nigerian military, Bello Matawalle, the Governor of Zamfara, last week offered the motorcycle-riding criminal gangs two cows for every weapon they surrender. “We are asking them to bring us an AK-47 and get two cows in return, this will empower and encourage them," Mr Matawalle said in a statement.

The unusual policy has provoked mockery online. But such solutions are not likely to be mooted if the Governor was receiving the support he needs from Abuja. A report by the International Crisis Group, a think tank, notes: “The state security presence on the ground remains too thin and poorly resourced to subdue the armed groups or protect communities across the vast territory.”

Meanwhile, criminal gangs across the country have turned to kidnapping for ransom. In in the vast middle belt, Fulani herders are locked in a grizzly conflict with farmers, exacerbated by climate change.

International investors and Africa-watchers love to talk up Nigeria’s potential. Undoubtedly, there is much potential in the country that has not been met. They focus on the country’s young, mobile and entrepreneurial population (70 per cent are under 30), a favourable investment environment in booming Lagos, low labour costs and impressive natural resources provision. For foreign companies establishing an African foothold on glitzy Lagos Island, conflict in the north seems a remote concern.

But that does little to assist ordinary Nigerians. Across the world, in countries rich and poor, the coronavirus has left governments floundering. But in Nigeria it completes a series of drawbacks just a year into Mr Buhari's second term.