As a child, growing up in Liverpool in the UK, I was fascinated with the objects at the local museum. During school holidays and even on weekends, William Brown street museum was my second home. On nodding terms with the security guards, my best friend and I, both aged 10, would wander the halls for hours. We saved the best for last and the visit always ended the same way: two boys at the Ancient Egypt section, noses pressed to the glass, marvelling at the mummies on exhibit.

The recent discoveries at the Saqqara necropolis, south of Cairo, reawakened my childhood fascination with mummies.

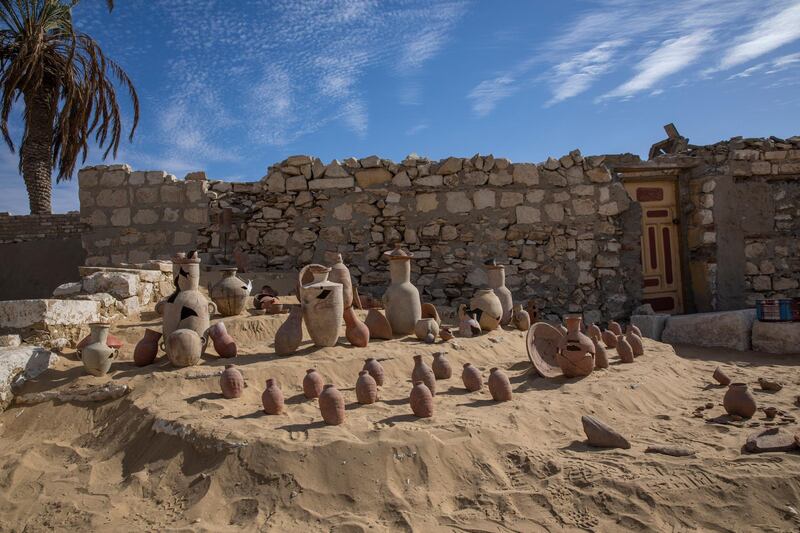

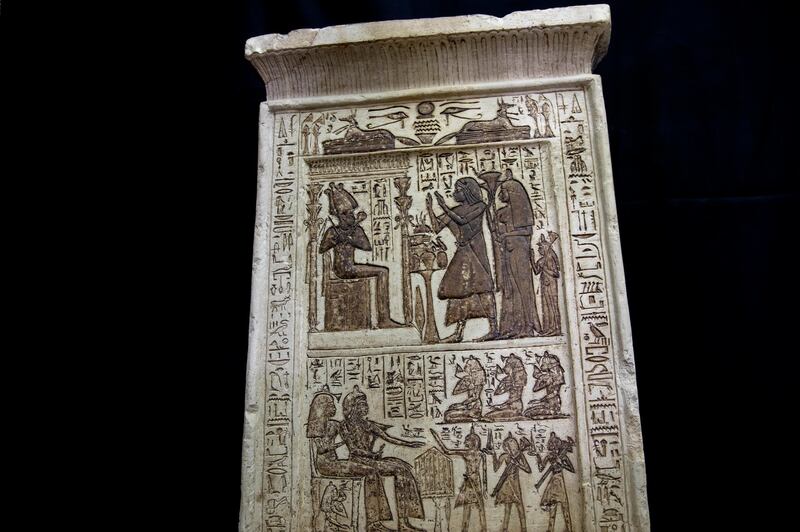

Towards the end of 2019, an Egyptian team discovered a large cache of ancient burials, including more than 50 coffins and several mummified animals. It was called the largest archaeological discovery in recent memory. Excavations continue and the site is now the subject of a Netflix documentary: Secrets of the Saqqara Tomb. Last week, Egypt's Ministry of Antiquities announced the discovery of the tomb of Queen Naert, along with grave goods and artefacts from about 4200 years ago.

Despite all the news of late about archaeological sites – or perhaps because of it – these days I find myself questioning the rights and wrongs of digging up human remains from their intended resting places, even as this is done for scientific reasons. How many samples do we actually need, I wonder. Even more so, I find myself conflicted about the ethics of putting human remains on public display. Yes, there is much to learn by looking but is it right?

Imagine if we were direct descendants of some of the exhibited. Would we be all right displaying, say, our great, great grandparents? Moreso, I wonder, would we be OK if, in due course of time, our remains were exhibited behind the museum glass or, say, displayed on the internet, for the class of 3021 to survey?

Another recent archaeological discovery, this time in Spain, raises similar questions. Late last year, a roadworks project led to identifying one of the oldest and best-preserved Muslim cemeteries in the Iberian Peninsula. The site has more than 4500 graves, of which about 400 have already been exhumed. These human remains belong to Spain's earliest Muslim community, dating back to the 8th century and the first wave of Islamic conquests.

These Spanish exhumations, although old, are not as comfortably distant as the ancient Egyptians of Saqqara. Which begs the question: how long ago do we need to have lived before we turn into fair game for funerary archaeologists? In some nations, 100 years is long enough.

Beyond being in the ground for hundreds rather than thousands of years the remains at the Spanish site were, in accord with Islam, all buried facing towards Makkah. The question arises: to what extent should the purported beliefs of the deceased be taken into consideration, and how much should the communities and faiths to which the deceased belonged have a role to play in the manner in which the remains are exhumed and subsequently handled by archaeologists?

These are not new questions. Nor is this a novel debate. However, I think it is a conversation that we need to revisit from time to time in light of our shifting moral sensibilities. After all, what was “all good” in 1821 or even in 1921 might spark outrage today.

Several nations have begun rethinking and updating the rules concerning the exhumation and reburial of historic human remains. For example, in the US, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act requires that remains and artefacts uncovered during excavations be returned to identified descendants or tribal groups.

Similar legislation in the UK prompted a community elder to launch a legal battle to have the human remains unearthed at Stonehenge reburied. The case was unsuccessful, but it is unlikely to be the last of its kind.

For some people, human remains are an especially sensitive issue, as they are connected to a sense of history, of belonging to a group and that belonging is deemed valuable.

Alexander Haslam, professor of psychology at the University of Queensland and editor of The social cure: Identity, health and well-being writes: "Social identities – and the notions of 'us-ness' that they embody and help create – are central to health and well-being." It is understandable, then, that the perceived mistreatment of ancestral remains can cause people great pain.

Historic human remains, however, helps us tell the story of humanity more accurately. They can even lead us to explore questions about complex contemporary social issues.

For example, researchers interested in domestic violence have used ancient remains to gather insight about possible gender roles, gender ratio and human behaviour across time.

Similarly, studying the bones of people who died of the black death during the 14th century has provided data to inform our fight against present and future epidemics.

Funerary archaeology is undoubtedly beneficial to piece together the past and learn the stories of our ancestors. But there have to be boundaries which must be reviewed every few decades, if not years.

When is it permissible to dig up remains and when is it OK to put them on display, online or in museums? Do human remains have human rights? As we evolve as societies, the answers to such questions are likely to change.

Justin Thomas is a professor of psychology at Zayed University and a columnist for The National