According to the Mayo Clinic’s nutrition and healthy eating webpage, up to 400 milligrams of caffeine a day, equivalent to four cups of brewed coffee, is considered a healthy consumption and can “increase wakefulness, alleviate fatigue and improve concentration and focus”.

In other words, coffee enhances our performance, which explains why hundreds of millions of people drink it in the morning before going to work. So here's a question for you: do you consider people who drink coffee to be more efficient during the day to be cheaters? It is likely that you don't. But in 1994, former Italian professional cyclist Gianni Bugno was suspended for two years for testing positive for caffeine levels above the prescribed limit. One could argue that the rules are different for athletes, who are expected to be role models. Fair enough – or is it?

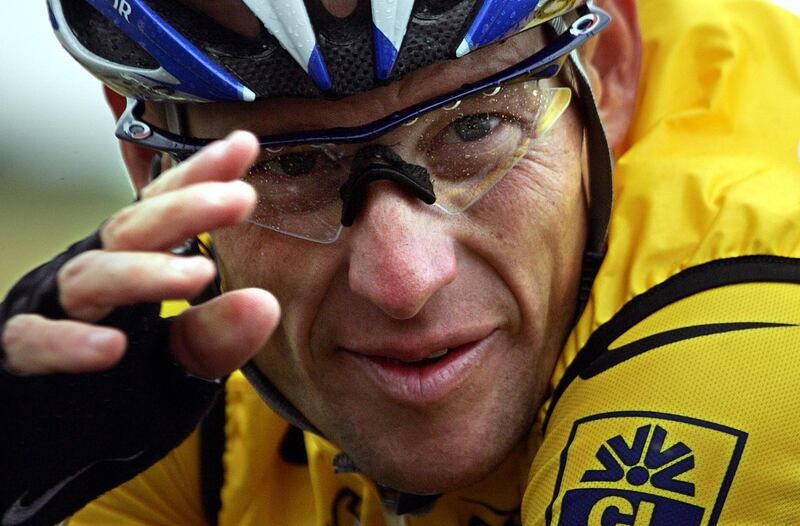

Bugno is a former two-time world champion and also a past winner of the Giro d'Italia, an annual multi-stage cycling race that begins this Friday. Controversy has plagued its build-up this year, thanks to the return of one man: Lance Armstrong. Not as a competitor – he is retired and banned from competing in cycling races – nor as an official guest but as a podcaster.

Another doping story, involving British cyclist Christopher Froome, has sparked furious debate in this year's pre-Giro media coverage. The best cyclist of the past five years tested positive last year for twice the authorised amount of Salbutamol but said he took it as a lifelong asthma sufferer.

Last week, early in the morning in an Atlanta coffee shop, I overheard two men talking at a nearby table. They had just read in a newspaper that Armstrong agreed to pay the US federal government $5 million to settle fraud allegations and therefore avoid a penalty of nearly $100m he was facing after being sued by his former sponsor, the US Postal Service.

One of the men was clearly upset and very vocal in his criticism and shaming of Armstrong. I could not help but see some irony in a man who was downing his second coffee in five minutes.

Despite a highly publicised confession during an interview with Oprah Winfrey five years ago, Armstrong still remains a pariah. I do not approve of his cheating nor the careers of other cyclists he allegedly ruined while in the peloton. But there are clear double standards here.

___________

Read more from Olivier Oullier:

[ We can all do our bit to stop antibiotic overuse ]

[ The power of two: how science and technology can be compatible in more ways than one ]

[ Evidence-based policy will save us all a headache ]

___________

There are various examples from daily life where performance-enhancing drug use is considered socially acceptable, whether it is coffee or – as I have heard in some cases – parents of children diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder taking their child's medication to be more focused at work.

Throughout history, there have been examples of people in the public eye enhancing their performance with contraband substances, whether it was Winston Churchill, Sigmund Freud, Jimi Hendrix, the Beatles or Vincent van Gogh.

Yet why, when it comes to art, is the use of drugs not considered performance-enhancing? Why is Armstrong stripped of his trophies but actors and artists are allowed to keep their Oscars and Grammys?

In the United States, some very respected neuroscientists have even advocated for cognitive enhancement drugs to be made available on university campuses to combat social inequalities.

In 2015, Professor Barbara Sahakian of Cambridge University was the lead author of an article in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, which stated that: "As a society, we need to consider which forms of cognitive enhancement (pharmacological, exercise, lifelong learning) are acceptable and for which groups (military, doctors) under what conditions (war, shift work) and by what methods we would wish to improve and flourish."

So far, it seems clear that as long as you are not an athlete, society on the whole is likely to turn a blind eye to performance boosters.

Even my childhood hero Asterix needed a "magic potion" to beat the Roman invaders. But Asterix was, I hasten to add, no athlete.

Enjoy your coffee and have a productive day.

Professor Olivier Oullier is the president of Emotiv, a neuroscientist and a DJ. He served as global head of strategy in health and healthcare and member of the executive committee of the World Economic Forum