As the US-China stand-off potentially reaches the point of no-return, there are growing fears across the globe about the implications of the tense relations between the two giants, each seeking to deny the other global supremacy. Recent developments in Hong Kong, where China imposed a new national security law, have exacerbated the recent strategic shift in their dynamic spurred on by the coronovarus pandemic and a trade war.

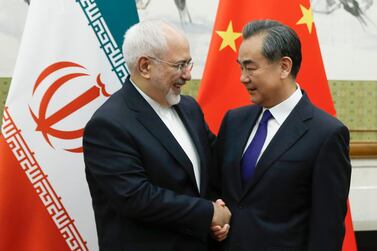

Now the US will seek to thwart a possible China-Iran pact by using sanctions to block financial transactions and by punishing Chinese banks. It may also attempt to block military deals between the two countries by lobbying to renew an arms embargo on Iran in the UN Security Council. China will perhaps be anxious about the repercussions of any sanctions on its financial system.

I believe Lebanon may prove useful to Beijing, which could seek to leverage that country’s financial system to avoid US sanctions. This, however, could lead to complications for Lebanon, which finds itself being swallowed up by the Iranian regime through its proxy Hezbollah. Speculation is rife amid reports indicating that Hezbollah recently obtained financial assistance from Tehran, which had in turn received funds from Beijing, as an incentive for clinching a deal.

Over the next couple of weeks, senior Hezbollah leaders are scheduled to visit Tehran to finalise a strategy for the coming few months. Meanwhile, Iran is preparing to leverage its influence in Lebanon and Iraq to serve its objectives in of thwarting US and Israeli interests in the region.

I am reliably informed that Iran's powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps intends to attempt to secure by the end of 2020 full-scale control of Lebanon by Hezbollah. Lebanon might also serve as a key base from which to take unspecified measures against Israel in September. The decision for the same is likely to be taken in an important meeting in two weeks.

Tehran may have chosen September for a combination of reasons. For one, it wants to be prepared for Israel's proposed plan to annex parts of the West Bank. Second, it seeks to hold Israel accountable for a series of sabotage attacks that took place on its soil, including explosions inside some nuclear facilities, which some experts believe may have been the handiwork of Tel Aviv. Finally, Tehran believes that it is in its interests to create a crisis for US President Donald Trump as he seeks re-election in November.

Iran's leaders believe that they have, in Lebanon, a wild card that they can use to impact the US election by potentially escalating an unwanted situation come September. Iraq, too, is an important asset for the regime in this regard. Tehran perceives Washington to be in election mode and therefore less inclined to intervene in the Middle East at least until November.

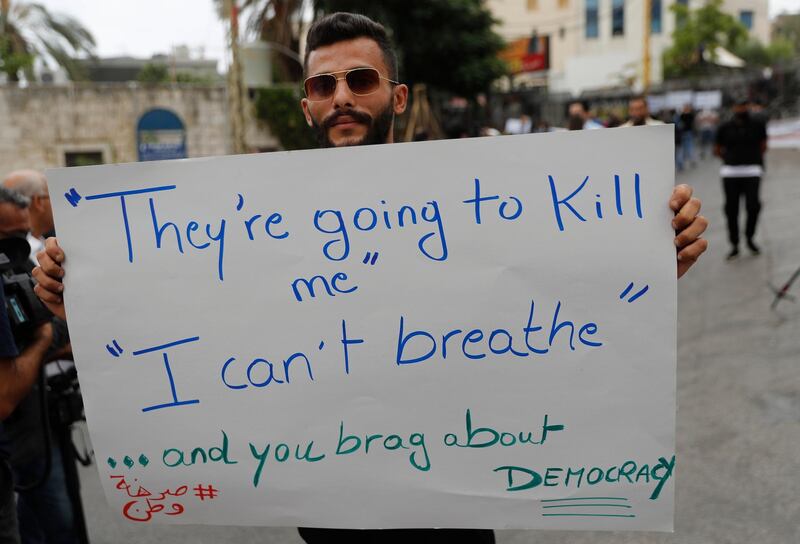

One of the problems is that the existence of Lebanon as we know it – a nation that has long prided in its neutrality – is under threat.

"The tragedy of Lebanon is that no one really cares," the American conservative commentator Danielle Pletka told me during the 12th e-policy circle of the Beirut Institute Summit in Abu Dhabi. However, Ms Pletka said that Hezbollah is in no condition to help Tehran if, for instance, it is asked to engage in a military conflict with Israel.

Abdulaziz Sager, the founder and chairman of the Gulf Research Centre, said few countries could help to fix Lebanon's myriad problems. "Maybe we need the Lebanese civil society to step in again to try to re-fix the situation in Lebanon," he said.

The question is, would China or Russia not be tempted to come to Beirut's assistance? Perhaps not the latter, according to Dmitri Trenin, director of the Carnegie Moscow Centre, even though he acknowledged Moscow's alliance of convenience with Hezbollah in the ongoing Syrian civil war.

“The alliances that Russia has today are very different from the alliances of the Soviet Union, or the alliances of the United States," he explained. "These are situational alliances for limited space, limited objectives, limited length of time."

He also pointed out that Russia does not support even Iranian policy across the Middle East. "Russia is with Iran for a certain objective [influence in Syria]. And even in Syria, Russia and Iran are in fact competitors, and the asset is playing one off the other," he said.

There is a school of thought that China, too, has very specific interests in the region and would be wary of stepping into the geopolitical morass of the Middle East. "China is about business at this point. It stays away from where it doesn't have the competence or experience," Mr Trenin pointed out.

One cannot forget the fact that China has interests and strong relations elsewhere in the region, such as in the Gulf. Beijing imports 32 per cent of its oil from the Gulf region, including 1.7 million barrels per day from Saudi Arabia. And yet, Mr Sager wondered if despite all this, Beijing is likely to ignore these relations in the context of its relations with the US. He said: "The whole US relation to China will have a massive impact on the Gulf."

It is not just the countries in the Middle East that are concerned by the US-China tensions. The Russians and Europeans are, too. There seems to be a sense that, even if Mr Trump were to lose in November, a president Joe Biden may take the same hawkish approach towards Beijing.

I am given to understand that, following a meeting in Washington earlier this month, a decision was reached at the highest level to create a multi-national coalition against China. Steps are already being taken in the meantime: expelling Chinese tech companies, shutting down consulates, attempting to thwart a China-Iran deal, and blocking off Hong Kong's financial access to the world in a way that would deny China any chance of leveraging the city's economy to its advantage.

China, of course, is not taking kindly to these steps, although it will also be wary of escalating tensions.

But with changing times and contexts, one cannot rule out the possibility of tiny Lebanon being drawn into the great power rivalry of the 21st century. By focusing on the big picture, the Trump administration may be oblivious of smaller countries. But it should know that one of the repercussions of an economic collapse in Lebanon would be even greater Iranian, and possibly by the extension of this greater Chinese, control there.

Whether Washington is mindful of this prospect now or later, Lebanon could on the cusp of a new, dangerous chapter.

Raghida Dergham is the founder and executive chairwoman of the Beirut Institute