When a crisis hits, two questions often swiftly arise. The first is: how do we respond? The second is: whose fault is it? While governments have struggled or succeeded in deciding what to do about the coronavirus pandemic, many in the political and media worlds have been busy pointing their fingers at those they hold liable for spreading, failing to contain or being inadequately prepared for the disease.

There has been a tidal wave of articles angrily bashing China, accusing it of being responsible for it all. Just this weekend, a report by the Henry Jackson Society, a British right-wing think tank, made headlines with its conclusion that the UK could claim up to £351 billion in compensation from Beijing for its supposed flouting of legally binding international healthcare regulations in the early stages of the outbreak.

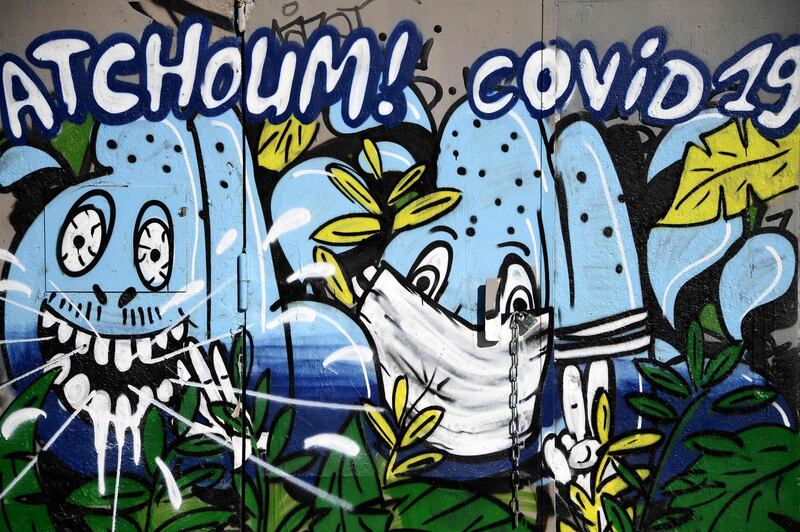

The well-regarded Foreign Policy magazine refers to what it calls "China's coronavirus misinformation campaign", while conspiracy theory crackpots have latched onto the idea that the virus could be spread by 5G telecommunications masts, presumably because of China's leading position in 5G wireless technology.

The attacks are aimed chiefly at Beijing, but not completely.

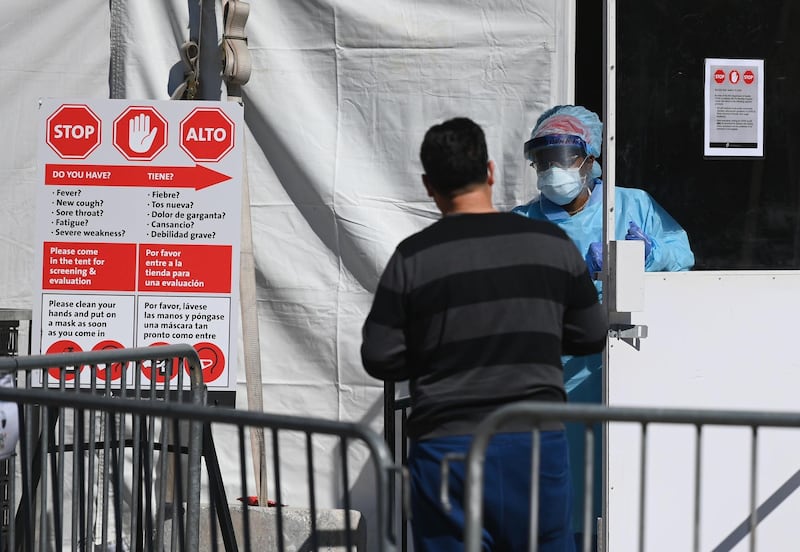

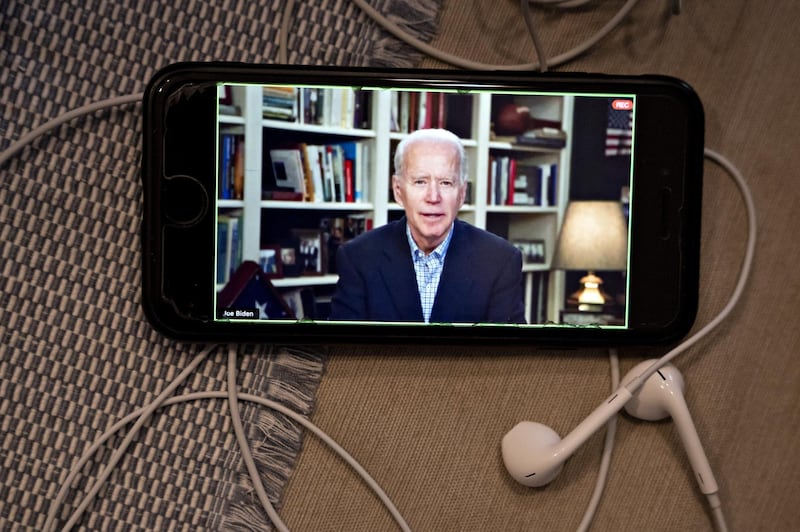

In the US, a former federal prosecutor, Glenn Kirschner, believes that as soon as President Donald Trump leaves the White House, he should be charged with involuntary manslaughter or negligent homicide at both the state and federal levels for the coronavirus deaths caused by what Mr Kirschner says are Mr Trump's “gross negligence” and “conduct of lying to the American people and downplaying the risk".

In Britain last week, the veteran journalist and former parliamentary candidate, Tim Walker, asked his 50,000 followers on Twitter if manslaughter charges should be brought “against certain individuals” – which he later made clear meant members of the country’s Conservative administration – for what he believes is their grievous mishandling of the situation.

Emotions are running high, and that is understandable. Almost all of us know friends or family who are at high risk of dying from the virus or of losing their jobs or businesses to what could well be the greatest economic depression (not just recession) of our lifetimes. And yes, we should certainly draw lessons from all that has happened so far and insist on as much transparency as possible. But I do not think that this is the time to assign blame.

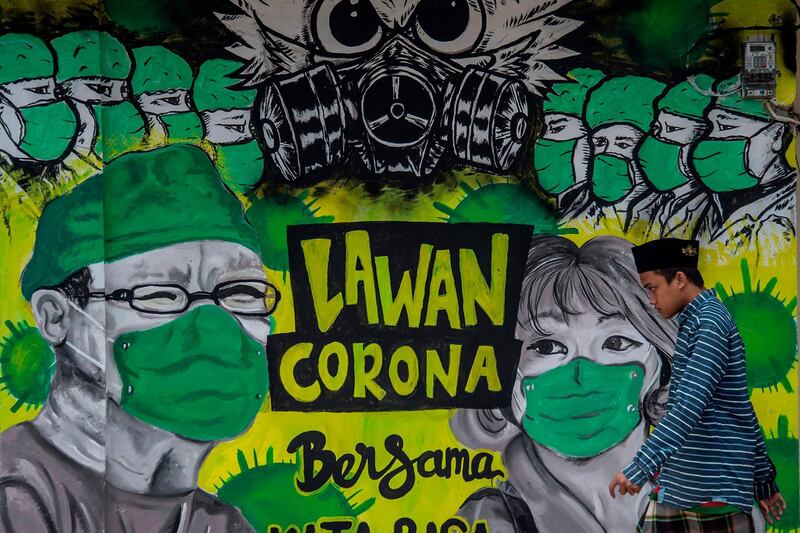

Quite apart from the need to reserve all our energies for combating the pandemic and the knock-on effects, there are several reasons not to be levelling grave accusations of guilt.

First, the idea – propagated, alas, by both Mr Trump and US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo – that China is somehow responsible for the coronavirus because it emerged in the city of Wuhan is ridiculous. Would we all have blamed West Africa if Ebola had gone global? History suggests not, as no one today castigates the Democratic Republic of Congo for being the source of HIV/Aids.

If Mr Trump wants to play that game, perhaps we should rename the “Spanish Flu” pandemic of 1918 “American Flu” – as evidence has come out that it was probably brought to Europe by US soldiers once they joined the First World War on the Allied side. But no. New viruses have no passports, recognise no borders and emerge from nature, not one nation or another.

Second, most governments have been trying to follow the scientific advice. The trouble is, that has been far from uniform, as the many, necessarily preliminary studies that have produced wildly different results and models show. That is why my relations in Sweden – whose government has been guided by the strategy of its own chief epidemiologist – have still been going to work and their children have been going to school, whereas we in Malaysia have been under virtual lockdown since mid-March.

This should be no surprise. The coronavirus is new. We do not have the luxury of waiting until the scientific community is fully informed. We have to act now when it is near impossible to be certain what the right approach is. Sceptics of long-term shutdowns, such as the former UK Supreme Court judge Jonathan Sumption, who question whether we have wildly over-reacted at an incalculable cost to current and future generations, could also turn out to be right. The choices we are having to deal with are universally unpalatable.

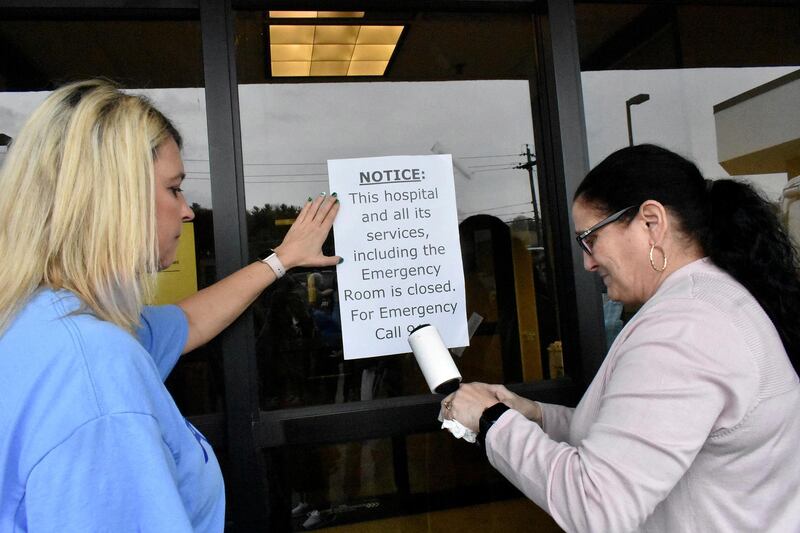

In such circumstances, of course, mistakes have been made, and all over the place. Europe and the US appear to have been complacent; having seen Sars and Mers essentially contained geographically and not turn into pandemics, they thought Covid-19 would peter out, too. If that had been the case, any serious restrictions to prevent the spread of coronavirus would have been condemned as draconian over-reach.

No government, including China, can claim it has acted perfectly, although critics who claim the authorities concealed the problem early on and might not be open about the scale of the deaths or infection should bear in mind that we have little idea how many cases the US, the UK and most other countries have either. But the idea that China has actually acted maliciously is preposterous. The country has suffered thousands of deaths, too.

This is not to say that governments should be given carte blanche for their actions during this period. But I do think it might be time to take a slightly more positive view of human nature and of our leaders. For all the advice they have access to, most of them are probably just as worried and baffled as the rest of us – and are trying to do their best. Nobody wished this on the world. Let us concentrate on saving it for now, and leave the blame game – where it is deserved – until later.

Sholto Byrnes is a commentator and consultant in Kuala Lumpur and a corresponding fellow of the Erasmus Forum