Wipe out half of March from the work calendar – and all of April and May. Does June line up as a zombie month as well? How long is the lockdown going to last all over the world, and can anything certain be said about the time horizon of the global fight against Covid-19?

Chancellor Angela Merkel, who has long held the role of “Mutti” – Germany’s mother figure – won plaudits for a clear exposition of the policymaker’s dilemma late last week.

She explained that the infection-rate was currently estimated around 1 in the country. This means that one person with Covid-19 is infecting one other person. If the rate – after loosening social isolation measures – rose to 1.2, the number of people needing treatment would rise by a fifth. Hospitals would get overwhelmed by the summer and the crisis would be measurably worse.

Merkel cuts through the political noise, explains with science and math how best to navigate the #coronavirus crisis.

— Joyce Karam (@Joyce_Karam) April 16, 2020

Helps that she’s also a Quantum Chemist: pic.twitter.com/lsVZRAoRQa

Forget the instant epidemiologists. Omar Ghobash, the Assistant Minister for Public Diplomacy and Culture, has talked of people becoming PhDs from the mythical "WhatsApp University". They are many – and their views are just as likely to be wrong as right.

Hard information is that the infection-rate cannot get ahead of the healthcare systems capacity to cope. Germany can claim some gains in its fight, largely as a result of their testing-based approach.

It has conducted 1.7 million tests and has pushed down the fatality rate among the diagnosed to 2.8 per cent. Its absolute death toll is a quarter of some of the worst-hit European countries, even as it is the most populous country in the region. However, it is worth pointing out that Germany also only records people whose cause of death was Covid-19 – not those with the virus at the time of death.

Britain is another nation that has been grappling with the pressures of lockdown. Last week, the London government established five tests to come out of the emergency phase. It did so as it announced “at least” another three weeks of the stay-at-home regime.

The announcement was made against the backdrop of the heavy cost of the crisis on the economy. Activity has ground to a halt since mid-March. That it has not been a uniform collapse makes the situation all the more complex, as a report from the Resolution Foundation, an independent British think tank, made clear on Friday.

“A sizeable minority of the workforce is no longer working, leading to falling incomes; welfare claims have surged; job vacancies have collapsed; and the majority of businesses have either closed or face falling turnover,” the report said. “The economic shock has not hit all sectors evenly: consumer spending has fallen much faster for some businesses than others.”

In the update, there was a sliver of hope in a suggestion that after the initial shock, job losses did not appear to be continuing to increase. It said that data showed applications for unemployment assistance had halved from a previous week peak of above 500,000. It also said online searches for jobs, which have a predictive relationship with unemployment rate, had returned to 2019 averages.

In the long-run, the downturn could turn out to be a great leveller, closing the gap between different parts of society. However, enforced work from home has the opposite effect: one survey estimated that while more that 50 per cent of those in the top 25 salary percentile could continue their job remotely, only about 10 percent of the lower percentile could do so.

Absent of any reliable guidance on when the ordeal will end, people have absorbed the idea they are caught up in wartime-style emergency. Not only are there comparisons being made between sheltering at home and the blackouts associated with the Second World War, but there is a mobilisation to assist others at a scale rarely seen since.

Barbour, the waxed cotton coat manufacturer, is one of many textile firms that have used their facilities to produce hospital gowns and other protective clothing for the local hospital. The head of the company, a venerable leader of a family business, described how the staff had enlisted in the effort.

Dame Margaret Barbour recounted how the firm had made sleeping bags for the trenches in the First World War and supplied uniforms for submariners in the Second World War. “It’s extremely worthwhile to know we’re playing our part,” she said.

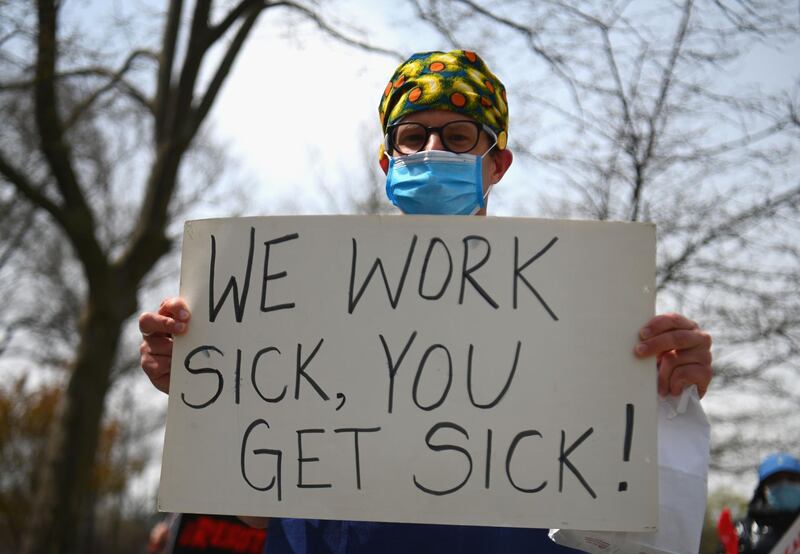

Only a subset of people will be able to play their part. For others, morale is a fragile thing. Security experts fear a rise in civil disobedience. Once incidents start, there could be a snowball effect.

Bad news both undermines the solidarity of wartime societies and creates a perverse incentive to break with self-denying behaviour. In the US, for instance, there was a far-right demonstration asserting a “right" to leave the home, a phenomenon that could proliferate.

So far, the evidence suggests that people are compliant in the face of a great disaster. Pushing into May and June could test that adherence.

Damien McElroy is the London bureau chief of The National