The convening power of the United Nations around its annual general assembly, otherwise known as UNGA, is one of the great strengths of the global organisation.

The UN secretary general’s yearly theme has the power to concentrate minds and affords a bully pulpit for a particular agenda.

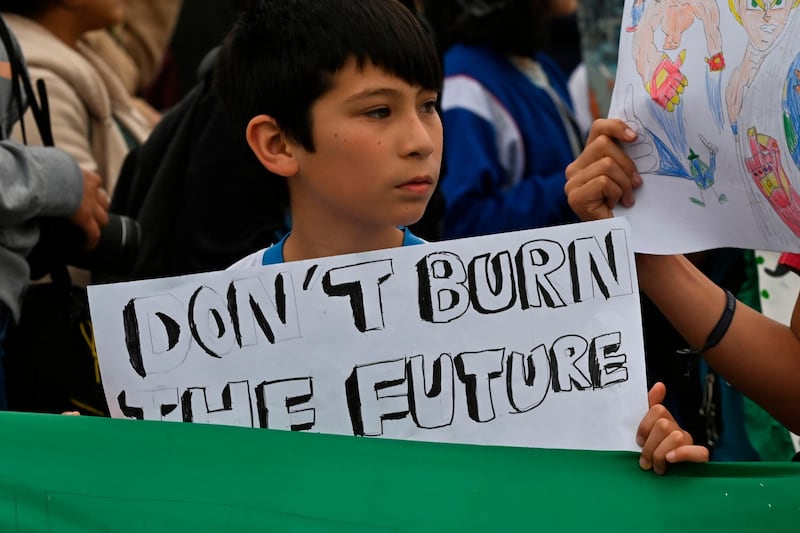

This week has seen the world's attention turn to climate change. A summit opening at the UN headquarters in New York on Monday will focus on the climate crisis and follows protests by an estimated four million people, who pounded the streets of their cities on Friday in the name of a global climate strike. For a short window, climate change will enjoy priority over peace-building, conflict or migration.

That is not to say that none of these issues are not linked or won’t be discussed. The nature of the climate crisis is that no factors stand in isolation.

It is appropriate that Antonio Guterres should have used this year's meeting to give primary focus to the environmental challenges faced by mankind. As the week progresses, world leaders will gather to give speeches from the marbled podium in front of the assembly. The messages of the climate summit will be repeated and reinforced alongside perennial national priorities.

Sir David King, a former chief scientific adviser to the British government, raised eyebrows earlier this month when he said he had been frightened by recent weather events. In particular, this summer's heatwave in Europe, the rate of loss of ice in Antarctica and the exceptionally slow progress of devastating Hurricane Dorian caused concern. These extreme events are occurring far earlier than the scientists in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had ever predicted. As such, the probability of people being affected by the consequences of climate change has grown much more likely.

“If you got on a plane with a one-in-100 chance of crashing, you would be appropriately scared,” observed Sir David as he explained why we should all be alarmed by what is happening.

The intellectual argument over climate change has been far more hotly contested than the science. As the UN summit opens, it is worth noting there are no counter-demonstrations of any significance planned. What was once a fusillade of sceptical commentary has now become the domain of a few.

The doubters once relied on popular but ropey arguments to advance their case. One dubious counter-claim was that if a glass of juice and ice was filled to the brim, it would not spill over as the cubes melted.

Extrapolate this to the planet and the argument was that the polar ice caps could melt but sea levels would barely change.

A tranche of columnists found a lucrative niche in plugging these claims. In Britain the anti-climate change cause was promoted by controversialists such as Dominic Lawson, Matt Ridley and James Delingpole.

Not all the writers who share climate doubts are from the right. Piers Corbyn, the brother of the Trotskyite leader of the British Labour party, was a paid-up member of the gang. A meteorologist, Mr Corbyn claimed to operate his own weather prediction service. This was predicated on the assumption that the warming of the planet was part of the natural cycle – therefore it was neither man-made nor reversible by behavioural changes.

Denying the endangering of the planet provided a lucrative career path for writers with this outlook for the best part of two decades. The US media similarly afforded airtime to climate doubters.

If you asked these advocates now, the majority would continue to adhere to their long-held views. There is a commonly held theory, for example, that global warming might be useful because the planet is entering a long-term cooling phase.

However, the appetite for such opinions is vanishing. The controversialists are finding their sometimes conspiracy-laden arguments have diminishing appeal.

A lot have moved onto other causes. The aforementioned names and others of their ilk are preoccupied with more homegrown issues, not least Brexit. Most are in favour of a blind leap into a brave new world of trade, and of ridiculing the array of experts throwing doubt on their arguments.

UNGA will be one of the few places where the doubters retain a strong voice. Certain world leaders balk at the idea of restraining growth or imposing supposedly nanny state policies to slow down the global rise in temperature.

Thus the climate summit is set to trigger rancour at the top table of international affairs in ways that it no longer does either in science or among the commentariat.

There is one sliver of hope as events kick off this week – that by airing differences on this and other topics, some of the wilder fringes of the argument ebb away.

At the UN, leaders have serious rebuilding to do on a whole range of issues. UN envoys to Libya and Yemen need real support and high-level backing this week. The plight of refugees must return to the spotlight. But first we must save the planet.

Damien McElroy is the London bureau chief of The National