Britain’s general election campaign scheduled for next month is proving to be a fascinating test-run for populist politics. A look at some of the policy pledges being made by leaders of the major parties reveals platforms wholly or substantially unrestrained by the ideal of balancing the national budget.

There seems to be a desire to radically depart from the four-decade cross-party governing consensus, which has proved highly influential around the globe. There is a real danger that the country's place in the global economy and diplomatic realm will shift radically as result of the December vote. This will also have consequences far more wide-reaching than the tortured Brexit project.

There are manifesto items that threaten the rule of law. In one respect, at least symbolically speaking, there appears to a shared drive to return to the medieval era. Let me deal with that claim first.

Almost all the parties agree that there should be a lot more trees planted in Britain to tackle climate change. The bidding war on foliage was triggered by a report from the University of Zurich earlier this year that claims 1.2 trillion trees could be planted on 1.7 billion hectares of treeless land. Scientists have said that two-thirds of carbon emissions could be absorbed by trees.

This is the manifesto that the most powerful people in Britain will tell you is impossible.

— Jeremy Corbyn (@jeremycorbyn) November 21, 2019

That it’s too much for you.

But this General Election isn't about them, it's about you.https://t.co/GlT6S8LUFK #RealChange

The epitome of populist parties is the Brexit Party. While it has not bothered to publish a manifesto, it did release a short, 20-page contract with voters. Nigel Farage, the leader of the party, promised to recruit US President Donald Trump, a climate change denier, and other members of the United Nations to plant “hundreds of billions” of trees on the planet. The ruling Conservative party has yet to publish its manifesto but it has already committed to 30 million trees. The Liberal Democrats have committed to double that number, while the Labour manifesto states its commitment to an “ambitious programme” of tree planting.

It is true that where the politicians have gone, large corporations are already leading. Airline companies Emirates and Easyjet, for instance, spoke about their offset activities last week. Still, the race to win the tree war tells a wider story of hyperbolic electioneering and manifestos unleashing the floodgates of unfunded and untested promises.

So far third in the polls, the Liberal Democrats have promised free childcare and a state-funded "skills wallet" to spend on re-training individuals in new technologies and industries over 30 years. Labour has issued a massive programme to march back to 1970s-era labour laws and state control of the economy. Free broadband services are its most eye-catching pledge. And it has promised to raise the annual amount the government spends by £80 billion every year it is in power.

Building on a quip in the 2017 general election that there wasn’t a magic money tree to fund state spending, Prime Minister Boris Johnson tore into the Labour plans as a magic money forest. More trees.

The opposition has also promised costly one-off nationalisation projects to be paid for with government bonds. These moves would take postal services, water supplies and railways into its control. Investors around the world are braced for years of legal battles to defend provisions in bilateral investment treaties that prohibit the seizure of assets.

The Conservatives' document will only be unveiled on Sunday but from what the party has talked about so far, it will also be a heavy-spending, tax-raising exercise in reversing much of the investment-friendly positions that have seen London entrenched as a global city. Late last week, a government minister said it would slap a three per cent levy on property purchases by non-Britons. A less friendly immigration system is also being rolled out and will be copper-bottomed by the manifestos.

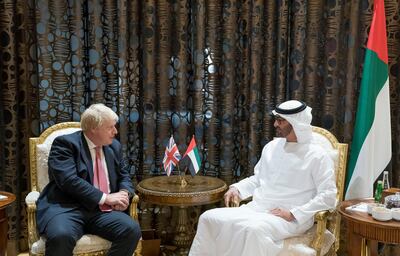

Victory for the Conservatives would at least hold the line at preserving, and maybe even deepening, the UK’s international alliances. For example, Britain would remain a strong security partner for the Arabian Gulf region. Last week, there was also a joint ceremony on using the stealth fighter jet – the F35 – across aircraft carriers belonging to Britain, Japan and the US.

Grant Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour leader, control of the national security apparatus and the effects would be immediate and dramatic. The manifesto commits to an immediate freeze on specific arms exports. It also points to a shift away from Nato with greater emphasis on working through the UN. Allegedly a long-term fellow traveller of radical groups, including Khomeinists, revolutionary terror factions and the Latin American populists, Mr Corbyn would alter the course of foreign policy just by walking through the front door of 10 Downing Street.

The problem is that once broken, long-standing ties are unlikely to be rebuilt and decades of work would be lost. That is true even if Mr Corbyn was to depend on the votes of the Liberal Democrats or Scottish National Party to sustain a minority administration. Speaking of the Scottish nationalists, within the UK an outcome that granted their party the balance of power could result in the break-up of the country.

In short, the election is a road-test in how far wild populist promises can carry politicians. It might even end up as a graveyard for capitalism or more likely the concept of "Global Britain".

Damien McElroy is the London bureau chief for The National