Management gurus tell us that if we want to embed change then we must destroy the symbols of an old culture and recognise and reward those who embrace the new. Presently schools are trying to champion both the supremacy of academic attainment in the same breath as broader educational achievement and innovation. With such a mixed message are we really giving our students the clarity they deserve?

Take for example the standard inspection framework in parts of the UAE, which sets a minimum level of attainment for all students in a school irrespective of their relative ability. Only if schools meet these minimum levels of attainment can they be rated as outstanding. At which point for-profit schools can then raise their fees by a multiple of the education cost index. Here we have the perfect example of a system whose symbols and structures are designed to reward schools that drive attainment over all else. They are financially incentivised and rewarded for meeting targets on academic attainment.

Ostensibly this seems to make a lot of sense and such frameworks are common throughout the world. Indeed why would you not incentivise schools in this way?

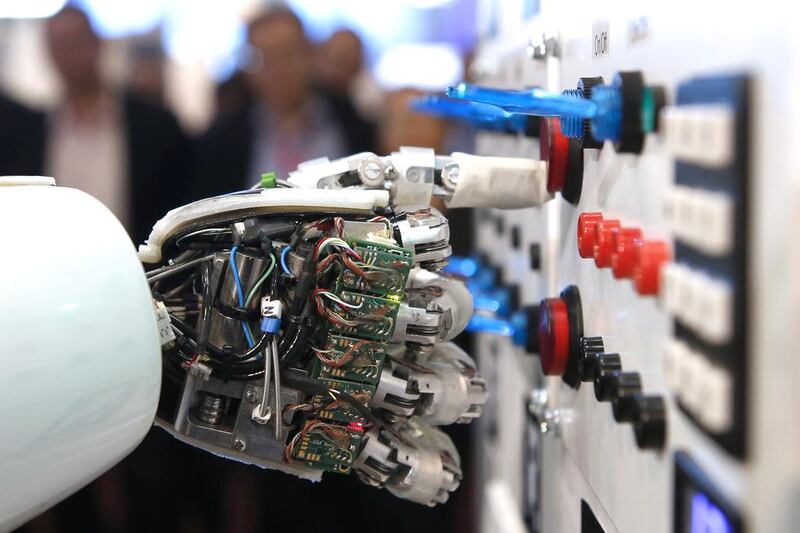

Research from the World Economic Forum suggests that today's students need to cultivate increasingly human skills which are very different to knowledge retention and regurgitation. Critical thinking, creativity, collaboration and communication skills must take primacy in our educational institutions if students are to remain gainfully employed in an increasingly digitised world which will see AI automate huge tranches of the labour market.

For the WEF the more sophisticated a student's human skills the more likely they are to remain immune to automation. And yet work by the author Lucy Crehan in her book, Cleverlands: The Secrets Behind the Success of the World's Education Superpowers, indicates that education powerhouses such as Finland and Singapore who perform especially well in the standardised global attainment tests of PISA, TIMSS and PIRLS tests do so by spending around three times as much time engaged in teacher-led instruction as they do in student-led instruction. The antithesis of what the WEF says we need to be doing.

So here we have an organisation, the World Economic Forum, in a relatively unique and privileged position to tell us what the world of work will need over the coming decades again colliding with global education systems who wish to see their PISA and TIMSS rankings increase. The type of skills the WEF says students will need sit firmly at the student-led instruction end of the spectrum. Yet for PISA and TIMSS scores to increase schools need to be engaging in much more teacher-led instruction.

So how do you square that circle? One radical solution lies in the forward thinking 10x Dubai project. Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice President and Prime Minister of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai, called on all Dubai Government entities to embrace disruptive innovation as a fundamental mantra of their operations and to seek ways to incorporate its methodologies in all aspects of their work.

Imagine if the symbols and structures of global inspection frameworks were altered to incentivise schools to exploit disruptive innovation in teaching to deliver lessons in radically different ways that are design-thinking-based and focused on the WEF skills and competencies. Quickly schools would adopt this approach if the rewards were sufficiently attractive. They would need protection from being downgraded and financially penalised, however, as educational change often leads to a drop in academic attainment in the short term.

The question remains are governments sufficiently committed to innovation and 21st century learning or will we continue to produce "incremental innovation", as 10x describes it, which focuses on making good services better for existing customers?

Michael Lambert is Headmaster of Dubai College