In 2020, the racial issues that perennially gnaw at the American soul erupted with the greatest intensity since the 1960s. While the present struggle is commonly viewed in social and cultural terms, it is fundamentally political. Above all, it is about defining the past in order to shape the future.

In the 1960s, at issue was the ongoing quest of African-Americans not to be subjected to overt or barely concealed discrimination. What's at stake now – in a battle that will be played out for many coming years – is the power of white Christian Americans, who have dominated the country since its founding, to continue to define and embody the national identity and retain political supremacy.

The slide of the Republican Party towards authoritarianism – dramatically demonstrated by the vows of at least 140 Republicans in Congress to vote on January 6 to reject the election results simply based on the outcome – is largely driven by such anxieties. Republican leaders increasingly and unapologetically oppose not just widespread voting but respecting disappointing election results.

Historically, this is a familiar conundrum.

It is easy to embrace equality and even democracy as long as a community can still determine the national agenda. But when political equality threatens to undermine communal power and unseat the authority of a once-dominant group, anti-democratic practices can easily be recast as existential necessities.

The presidency of Barack Obama was viewed by many as unacceptable and a stark, alarming warning. Forced to choose between upholding democracy or risking their power, a significant proportion of white Christian Americans, especially outside the great cities, are embracing anti-democratic minority rule.

The Trump administration embodied such terrors, breaking with traditional Republican orthodoxy most dramatically on immigration. In a few months, Mr Trump and his base turned most mainstream Republican leaders from business-friendly immigration advocates into racial and cultural hysterics.

His election appeals to "suburban housewives" and obvious antipathy towards black-majority cities, their political legitimacy, and the threat their people supposedly pose to allegedly besieged white suburbia, encapsulate the racist subtext. His supporters aren't merely concerned about the demographic emergence of a US with no clear ethnic majority, they dread losing control of the defining historical and political narratives.

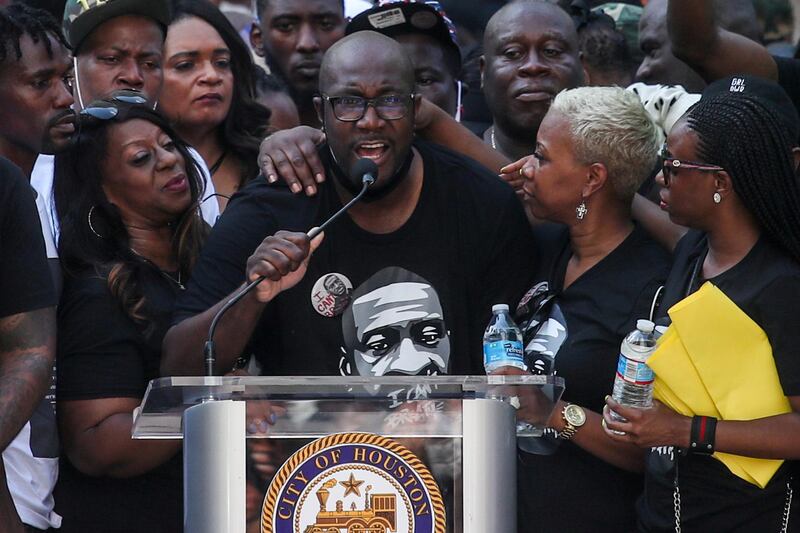

Thanks to smartphones and social media, last year was a watershed on white perceptions of racism. Unending footage of racist abuses from often deadly police brutality, such as the killing of George Floyd, which sparked weeks of multi-racial protests, to incidents such as the recent physical attack on a black child falsely accused by a white woman of stealing her mobile at a New York hotel, broke through thick layers of past denial.

That African-Americans, particularly young men, are routinely treated unfairly and even brutally by the authorities, and sometimes by their fellow citizens, is now widely accepted. Once-hegemonic views that ongoing systemic racism is a myth or that racism was largely resolved by the civil rights movement of the 1960s are now broadly discredited.

That is a massive transformation of white perceptions, with huge implications. Overt opposition to racism, such as kneeling during the national anthem or in solidarity, was once vilified but is increasingly common and often adds to one's respectability. Even Congress just overrode Mr Trump's veto of a military spending bill he rejected because it instructs the military to stop honouring confederate generals who led the Civil War fight to preserve slavery.

Predictably, though, anti-racism and leftist forces are also prone to overreach.

Using the slogan "defund the police" to call for badly needed policing reform was a huge mistake if the goal is actual change, because it was easily made to sound like a call for no policing. The "Black Lives Matter" principle opposing police brutality had to overcome tough resistance, because although it obviously meant "black lives matter too" it was often misrepresented as "only".

The well-intentioned and influential but badly botched “1619 Project", which seeks to recast US history with slavery as its centrepiece, was correctly dismissed by leading liberal historians as clumsy and sometimes glaringly inaccurate. Cringe-worthy overreaching is amply illustrated by a San Francisco initiative to rename an "Abraham Lincoln school" because "the great emancipator" was insufficiently anti-racist.

Perhaps the widest, most telling chasm has opened over widespread workplace anti-racism training.

The Trump administration, which has banned such training for federal employees, and much of the right denounce any analysis of white privilege as "anti-American propaganda". They fiercely, though preposterously, deny that there is an ongoing plague of implicit and institutionalised racial bias.

Yet such training can also involve negative stereotyping, with “whiteness” sometimes depicted as representing positive human traits such as “hard work” and “rational thinking". Some courses can feel unfairly, even ritually, condemnatory of well-meaning white Americans. That's distinctly unhelpful.

Assuming the US remains a democracy, which it fully became only after the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was implemented, the outcome of this macro-historical contest is unclear. Is the Trump presidency a last stand or the resurgence of traditional, intolerant white power?

A key unexpected feature of the 2020 election was a significant surge in support for conservative Republican candidates among some Latino and Asian-American communities. Despite nearly ubiquitous assumptions, non-white votes are not necessarily Democratic.

One likely gambit to bolster the self-identified white community’s political heft is the repetition of previous decisions (regarding Irish, Italians and so on) to redefine “whiteness” in a more inclusive manner. Millions now usually categorised as "Latinos" already essentially view themselves as "white", so a simple adjustment of inherently arbitrary definitions can reshape the demographic equation overnight.

Liberals are winning most of the cultural, if not the often structurally lopsided political, battles. Momentum is with anti-racism. However, both sides in the contest for cultural hegemony and concomitant political dominance in coming decades are counting on facile, possibly incorrect, assumptions.

Republicans and their non-urban white conservative base probably don't need to embrace overly racist identity politics or reject democracy to remain politically potent. But they seem convinced they do and that it is therefore rational and even defensible. That’s leading them in tragic and terrifying directions on both race and democracy.

Hussein Ibish is a senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute and a US affairs columnist for The National