There were two big winners in last week's British general election. One, obviously, was the prime minister Boris Johnson. But the other is the First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon. When it comes to figuring out the future of the UK, her words are worth remembering. Ms Sturgeon’s Scottish National Party (SNP) took 48 out of Scotland’s 59 seats. The key passage in her victory speech was this: "Scotland has sent a very clear message – we don't want a Boris Johnson government, we don't want to leave the EU. Boris Johnson has a mandate to take England out of the EU but he must accept that I have a mandate to give Scotland a choice for an alternative future."

She is demanding a second referendum on Scottish independence. Mr Johnson of course has other plans and priorities, and can refuse to grant Scotland a referendum. But that won't bring matters to a close. Mr Johnson's key promise and winning election slogan was to "get Brexit done" but as US President Donald Trump knows to his cost – and Mr Johnson is about to find out – turning slogans into reality isn't easy. Mr Trump's wall has not been built. Mexico is not paying for it.

Similarly, getting Brexit "done" continues to mean different things to different people. No serious trade expert thinks Britain can conclude a satisfactory deal with the European Union by the end of Mr Johnson's self-imposed deadline of December 2020, unless the British prime minister surrenders on every key point and so-called red line. Meanwhile Mr Johnson is also leader of what is formally called the Conservative and Unionist Party, and talks of being a "one nation" Conservative.

The trouble is that Mr Johnson speaks of Britain, but acts for England. He won the election on a wave of English votes. Brexit itself is a manifestation of English nationalism. Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU. In Belfast, Democratic Unionist Party MPs are furious that Mr Johnson surrendered previous red lines to accept a customs border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. There is therefore agitation for a referendum on Irish unity as well as Scottish independence.

And yet there are big political risks – not just for Mr Johnson. Ms Sturgeon’s SNP had a huge win in seats but has just 45 per cent of the vote – not enough to win independence, yet close enough to encourage it to try. And the arithmetic for Mr Johnson is also not as wonderful as it appears. He won by a landslide in seats but the majority of the British people – 53 per cent – voted for parties opposed to his Brexit.

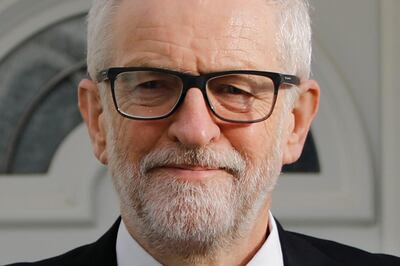

And that brings us to the losers. The Liberal Democrats, the most pro-EU party of all the major players, had a disastrous election. The party's leader Jo Swinson lost her own seat. Labour, meanwhile, has suffered its worst defeat since 1935. The blame rests squarely with the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn and the clique of hard-left doctrinaire figures with whom he surrounded himself. Labour MPs say Mr Corbyn's name was toxic when they canvassed voters in their constituencies.

Even the Labour leader's greatest achievement as leader is haunted by failure. When he lost the previous election in 2017, he didn't lose as badly as had been predicted. Last Thursday he tried again and failed even more spectacularly. His time is up. In reality, it was up long ago but he refused to admit it. When Mr Corbyn and his clique boasted about being "socialists", it turned off millions of British voters who saw him as a reheated Marxist dinosaur from the 1970s. And so the fight is now on to turn Labour towards the centre and social democracy, the combination which won them three landslide victories under Tony Blair.

That fight will be vicious. The Corbynistas continues to blame anyone but their own leader for their utter humiliation at the hands of voters – rather like Oscar Wilde’s supposed quip that his play was a great success, it was the audience that was a failure. Yet in Scotland, the audience for Labour has long gone. North of the border, Labour – once the natural party of government – is virtually extinct. To reinvigorate itself, Labour needs not just a new leader but new ideas.

And here’s a prediction. The centre ground of British politics traditionally is where the votes are. As the Conservatives pull to the right and Mr Corbyn’s fails on the far left, the centre ground is empty. If Labour does not move quickly to the centre, Mr Johnson himself will pursue his “one nation Conservative” ideas and try to capture the middle ground. While Labour fights its interminable civil war between socialism and social democracy, Mr Johnson really has no political philosophy. All he cares about is winning, which is why he will say anything and break any promise to stay in power. Despite the challenges ahead, he might be prime minister for many years to come. Winning in politics is not the most important thing. It’s the only thing.

Gavin Esler is a journalist, author and presenter