Many questions are raised by the death of Iranian commander Qassem Suleimani. Had Donald Trump, the US president, thought through all the repercussions for the region and beyond before ordering the drone strike that killed him? Unfortunately, that seems unlikely. Will it make America safer? Former US president Barack Obama's national security adviser Susan Rice thinks not; and neither, evidently, does the US state department, which has advised its citizens to leave Iraq immediately.

I will leave the immediate future to others to debate. My question about Suleimani's killing is simple: was it legal?

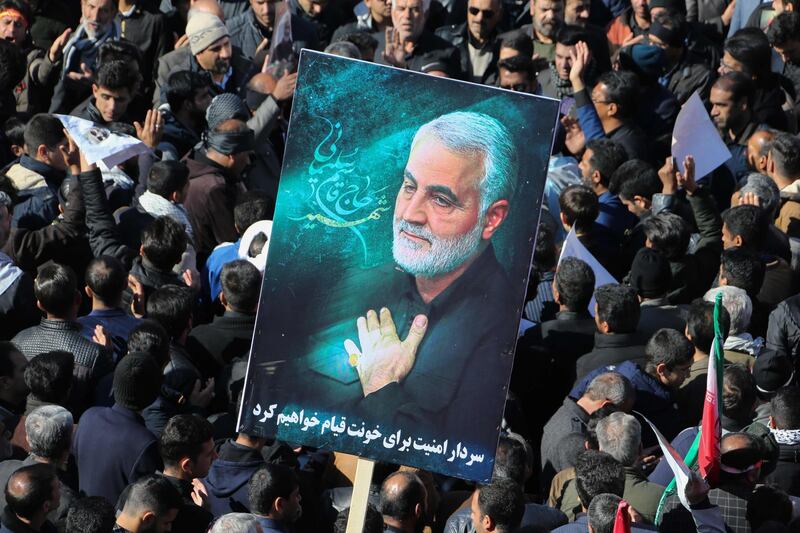

Some might ask why it is worth bothering with such pettifogging niceties. Was Suleimani not, like Osama bin Laden and Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi, responsible for thousands of deaths? Did he not deserve the same himself? As commander of the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and arguably chief executor of Iran's aggressive interventions abroad for decades, including its military backing of Bashar Al Assad in Syria and Hezbollah in Lebanon, his responsibility is undisputed.

The difference is that bin Laden and Al Baghdadi were outlaw terrorists, and it is doubtful that either could have been taken alive, even if there had been any desire to do so; Al Baghdadi blew himself up when cornered by anti-ISIS forces, and bin Laden had weapons in his room when he was shot to death by US Navy Seals in his hideout in Pakistan in 2011.

The IRGC might have been designated a terrorist organisation by the Trump administration but that was only last April. And Suleimani, by contrast, had been a very high-ranking general in Iran for more than 20 years. Many believe that he was the second-most important figure in Iran, more powerful than the elected president.

Even if the attack was to prevent imminent attacks on US personnel, as the White House has put forward as justification – which is disputed – it has been unprecedented since the Second World War for one state to claim openly that it had the right to assassinate senior officials in another. Agnes Callamard, the United Nations special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary killings, was clear. The targeted attack on Suleimani and his companions, she wrote on Twitter, was likely "unlawful" and violated international human rights law. "Outside the context of active hostilities, the use of drones or other means for targeted killing is almost never likely to be legal."

This matters deeply because the US has been the foremost advocate for an international rules-based order founded on the rule of law since the mid 20th century. In 1958, former US president Dwight Eisenhower even declared May 1 to be known henceforth as "Law Day" and said "the world no longer has a choice between force and law. If civilisation is to survive it must choose the rule of law." Nearly all his successors have echoed him one way or another. Until Mr Trump – whose official, rather than covert, assertion of the right to kill extra-judicially is by definition outside of and entirely contradicts the rule of law.

As Professor Patrick Porter, a leading international relations academic, put it in the aftermath of the attack: "You can argue for a special prerogative to carry out such killings. Or you can argue for a rules-based order that binds all states. But doing both at the same time... looks just plain ridiculous." He pointed out that using the same logic, Russia could have justified assassinating CIA officials in the 1980s, on the grounds that they were sponsoring jihadist opponents of Afghanistan's Soviet-backed government.

It seems unlikely that anyone in the Trump administration would look kindly on such an argument. Neither, however, are they willing to address the fact that when the US shows it is willing to flout international law, or even norms, it weakens the whole rules-based order it has supposedly been fighting endless foreign wars to uphold.

There are of course times when countries feel that they have genuine claims that international law does not and will not recognise. When Vladimir Putin, the Russian president, annexed Crimea from Ukraine in 2014, the international community condemned him but it was true that until 1954, Crimea had been part of Russia for more than one-and-a-half centuries. Its transfer as a “gift” to Ukraine by the then Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was an essentially symbolic redrafting of borders within the greater USSR. The area was still overwhelmingly Russian and should not, perhaps, have been separated from its motherland by the break-up of the Soviet Union.

There is no doubt that many Chinese are sincere in their claims to most of the South China Sea, despite the protestations of the local rival claimants who say there is no historical basis to them whatsoever. Many Irish nationalists regard it as a grave injustice that the six counties of Northern Ireland remain under British rule. The people of the Chagos Islands had to wait 54 years for the UN's highest court to declare that the UK's detachment of their archipelago from Mauritius during decolonisation in 1965 was unlawful.

So, no, the international rules-based order is far from perfect and does not provide solutions that satisfy all. It has to be maintained even in the face of countries and state actors like Suleimani that show no respect for it and who pursue their interests with complete disregard for borders, laws and the integrity and sovereignty of other nation states.

I have argued time and again that the global rules-based order's regulations and institutions need to be reformed drastically to reflect the world of the 21st century, rather than the Anglosphere dominated years in which the US and the UK created most of the critical global architecture – from the UN to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund – that persists to this day.

But that requires defending the principle of that order, even while all should accept that it needs a radical reworking. For we would be in a truly Hobbesian world – in which brute might, not rights and laws, would be the chief determinant of relations between nations – without it. The great powers must lead by example and, if there is to be any American exceptionalism, it should be as the greatest upholder of that order, even when it might not be convenient for it to do so.

The almost certainly illegal US killing of Suleimani suggests that Mr Trump has not the slightest care for its maintenance. He should do, for if it were to crumble we would all miss it – even him.

Sholto Byrnes is a commentator and consultant in Kuala Lumpur and a corresponding fellow of the Erasmus Forum