When journalists descended on the embassy of Ecuador in London earlier this month to meet the fugitive whistle-blower Julian Assange, expectations of a news-making announcement were high.

He has been holed up on “Ecuadorean soil” for more than two years after seeking sanctuary at the embassy in the face of attempts to extradite him to Sweden. Summoned to face the WikiLeaks man, reporters sensed a media storm.

But they were to be disappointed. A tight-lipped Mr Assange, who fears that extradition could eventually lead him to be handed over to the US over publishing US military documents, made the less-than-explosive announcement that he would be leaving the embassy “soon”.

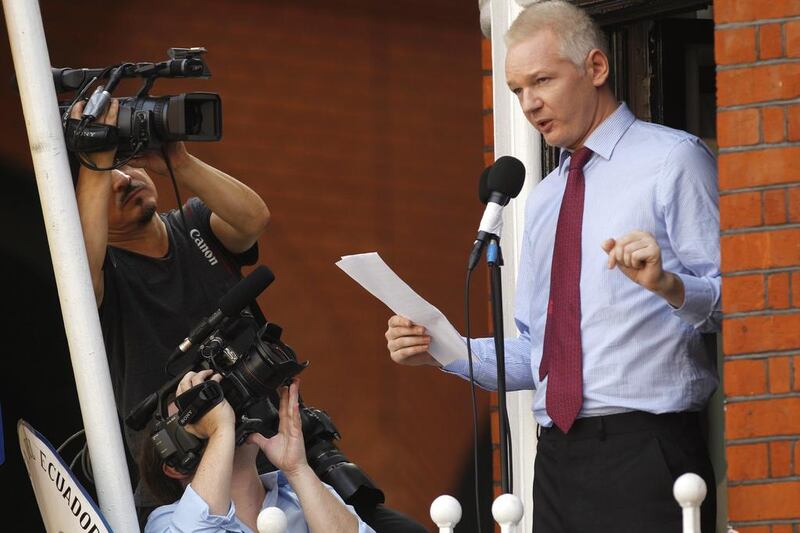

It was a far cry from his appearance on the embassy balcony on December 20, 2012, when he said: “When our media is corrupt. When our academics are timid. When our history is filled with half-truths and lies. Our civilisation will never be just. It will never reach the sky.”

It was the kind of rhetoric that has come to symbolise Mr Assange and his pursuit for “truth” and “justice”, a conviction that has made him loved and loathed, even if it was clearly lacking in his demeanour last Monday.

Whistleblowers are not like the rest of us. And, how could they be? Way out on the fringes of the political mainstream, they seem willing to dedicate their lives to ensuring that the most powerful in our world do not go about their business with impunity. And seem prepared to suffer the grave consequences that come from doing so.

US Army private Chelsea Manning (formerly Bradley Manning), who is serving a 35-year jail sentence for disclosing secret documents to WikiLeaks, and former American intelligence officer Edward Snowden, who fled to Russia after revealing the US government’s surveillance programmes, are two other figures who will forever be defined by their actions.

And, as Mr Assange’s press conference clearly shows, today’s whistle-blowers have an uncanny ability to stop the world in its tracks. Mr Assange may divide opinion – to many, his reputation as paranoid and controlling is not without foundation – but in discussing whistle-blowing itself it is necessary to look beyond the actor and more at the act.

Indeed, in concerning ourselves too much with the character of those who would give up state secrets without serious consideration of their own personal safety and integrity, it is easy to forget how important whistle-blowing remains to our understanding of the world.

I am writing from the UK, where a Westminster whistle-blower rocked the British political establishment in 2009 over MPs expenses.

In Tunisia, and in a more internationally profound exposé, WikiLeaks exposed the rule of the country’s former president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and his family’s corrupt and extravagant ways. The leaks were explosive.

One uncovered US diplomatic cable written before the revolt revealed: “Tunisians intensely dislike, even hate, First Lady Leila Trabelsi and her family. In private, regime opponents mock her. Even those close to the government express dismay at her reported behaviour. Meanwhile, anger is growing at Tunisia’s high unemployment and regional inequities. As a consequence, the risks to the regime’s long-term stability are increasing.”

Just a few short months ago, Mr Snowden was elected rector of the University of Glasgow, one of Scotland’s oldest seats of learning. For one whose job is to represent the university’s students, the notion of an exiled Mr Snowden doing justice to the role is not credible.

Yet, just as students at the university elected Winnie Mandela as rector to symbolise their opposition to apartheid South Africa in 1987, so they’ve now elected a figure who chose to tell the world of an injustice that has made him one of the most outlawed men in America.

Indeed, the sensational nature of the secrets spilt by the Assanges and the Snowdens of this world – and the audacious and unapologetic manner in which they pulled it off – have already become defining moments in a century that is still in its infancy.

Alasdair Soussi is a freelance journalist, covering the Middle East and Scottish politics

On Twitter: @AlasdairSoussi