At the very first meeting he attended of the International Cricket Conference (as the ICC was then) as head of the Pakistan board, Nur Khan told those around him he was ashamed to be sitting with them.

"I've been involved in other sports and they solved issues by building a proper institution, not a private body like the MCC," he later remembered. "I said aren't you ashamed after so many years that hockey and other sports have 80-90 members? Squash had many countries and here you are only six or seven after so many years?"

Khan died last Thursday in Islamabad at the age of 88; three years ago when I met him on a spring day, the skies over Islamabad fresh and honest, he stood as he spoke; unbent and upright.

He was probably the greatest all-round administrator Pakistan has seen and cricket, which he headed from 1980-1984, was not even a sport he liked. As a military man – he was an Air Marshal and led the air force in the 1965 war with India – cricket wasn't manly enough for him; boxing, squash and hockey were his passions.

That first ICC meeting set the tone for a transformational and visionary tenure.

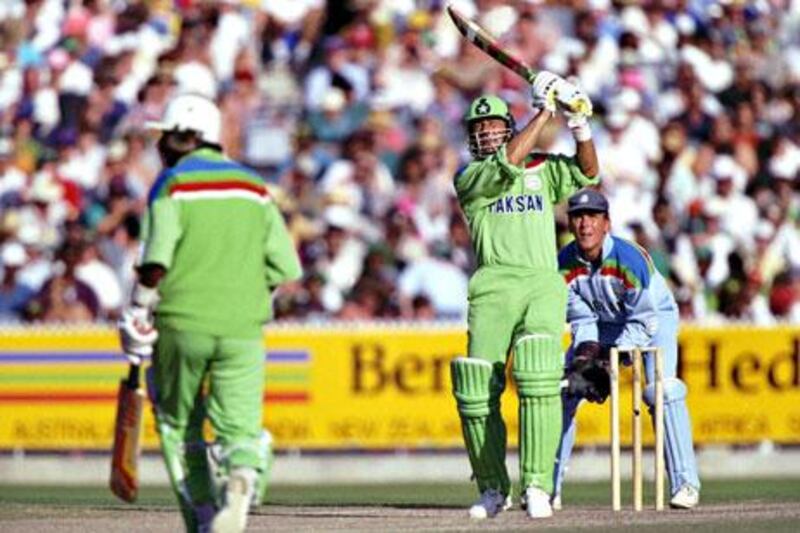

Khan's experiences heading hockey and squash had opened his mind far beyond the cosseted world of cricket. It was Khan, for example, alongside NKP Salve, the former Indian cricket head, who won the bid to host the 1987 World Cup in India and Pakistan, the first time it would be outside England.

The idea had come the day after India's World Cup triumph in 1983, at Lord's itself.

Over some biryani at the official lunch, Salve, with whom Khan had forged a warm relationship resulting in annual series between India and Pakistan, wondered aloud how it might have been had the final been in India. Immediately, records Salve, Khan jumped on the idea.

"Why can't we play the next World Cup in our countries?" That same year, 1983, Khan helped put together the first Asian Cricket Conference, a key moment in the rise of the bloc to dominance a decade later.

Of equal significance was his disdain over the long-standing, increasingly fractious matter of umpiring. Fed up at the constant sniping among countries, Khan's first reaction was to see this as a global blight and pull out his own leaf from hockey: neutral umpires.

"You come to my country and call us cheats because of the umpires," he told ICC officials. "We go to your country and have the same issues. It can't be this way. How can you carry on like this?'"

He invited four neutral "observers" to informally monitor umpiring and general behaviour on the field in a series in Pakistan in 1980.

He even sent Intikhab Alam as a neutral observer for some Tests in the Caribbean and pushed for the ICC to review how umpires were appointed.

"The British, Australians and New Zealand all resisted the idea of neutral umpires," Khan said. "Their umpiring lobby was very strong. But they used to complain against each other as well. The British used to say you have to be twice as good in Australia."

Only years later did cricket come round to his thinking.

There was so much more.

In trying to find an honourable way to ease out Mushtaq Mohammad, Khan got him to retire and become the side's coach-manager, one of cricket's first such appointments.

And though he first chose Javed Miandad over Imran Khan as captain (Imran was too much the playboy at the time, he thought), he was eventually compelled to go for Imran in 1982, a decision that changed Pakistan. He is actually a man for a book, not a cricket column because the special dust he sprinkled revived a number of organisations across generations.

Twice he breathed life into Pakistan International Airlines (PIA), in two vastly different decades, the 1960s and 1970s, stints that are remembered each new day of loss and decay with greater fondness.

Twice he headed hockey, each time, not coincidentally, Pakistan finding itself at the sport's summit. He introduced the idea of a hockey World Cup and the Champions Trophy.

Squash he ran informally, for love, and though the greatest of them all, Jahangir Khan, would have been found anyway, Khan's nurturing ensured Jahangir lacked for nothing in his drive to the top.

He wasn't easy to work with; men of both crisis and vision aren't always.

Omar Kureishi, the great writer-broadcaster who worked with him at PIA, reckoned him to be of "clear-cut views on most matters, a closed mind but one who leaves a window open.

"That was his management style, an impatient man who was result-oriented, a competitive man because he sought the best, brooked no nonsense."

A number of people were rubbed the wrong way. Often he would lose his cool, in typically military-man fashion. But he remained beneath, as showed the eyes even late in life, an essentially compassionate soul.

They were bad days when we met. Cricket was littered around messily, in a great pigsty of a land. We spoke long, about handling superstars, management and much else, his views as sharp and clear as the air that day.

Throughout I felt the nerves of a man meeting a prospective father-in-law, skirting around all manner of topics stiffly, not revealing too much, not knowing too little.

As I left, he said he hoped he had been useful. He couldn't have known just how much.