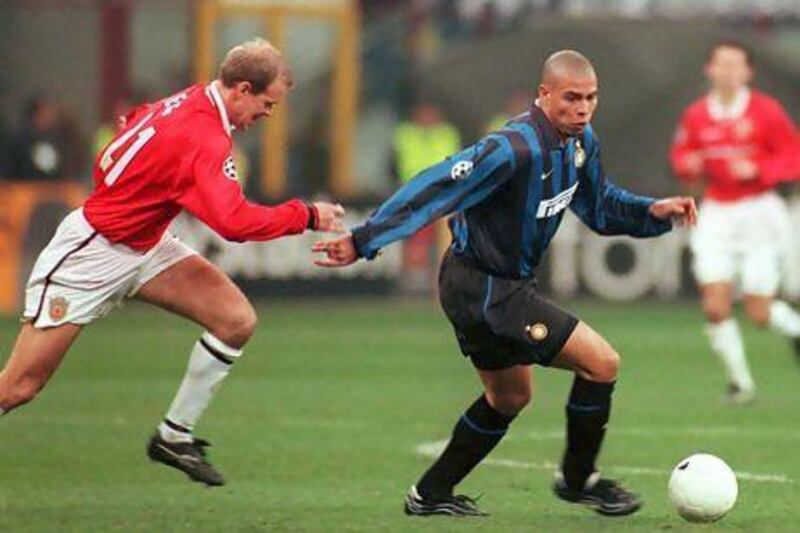

The word before the game was that Ronaldo was only 60-70 per cent fit. I'm talking about the Brazilian Ronaldo, the greatest player in the world in the late 1990s.

I played against him in 1999 for Manchester United against Inter Milan in the Champions League quarter-final second leg. We had won the first leg, 2-0, and they brought him back for the second. Even though Inter had Diego Simeone, Roberto Baggio, Ivan Zamorano and Javier Zanetti, they only had one player who could win a game by himself.

Sir Alex Ferguson knew he wasn't fully fit. He encouraged us to get the ball out to our full-backs, Gary Neville and Denis Irwin, because he didn't think Ronaldo or Simeone would have the energy to hunt the ball down. He was right and Simeone, who had been winding the players up in the tunnel before the match, was substituted after half an hour.

Ronaldo played for an hour. You could tell he couldn't move as well as he wanted, but when the ball came to him, he was still an immediate danger. He was heavier than he had been, but was still so dangerous that we tried to keep the ball away from him. If he got it, then his step-overs, superior technique, speed, power and directness would cause trouble.

Ronaldo may have only been 60-70 per cent, but he was still magnificent. He could have played up front for us in place of myself and Dwight Yorke and still run the show.

I wouldn't have liked to play against him when he was at 90 per cent. But 100 per cent? Don't be silly. No footballer fitness is ever 100 per cent.

Michael Owen - the retiring former England and Liverpool striker - admitted on Thursday that he hadn't been 100-per-cent fit since he was 19 and picked up a hamstring injury. People expressed surprise. I didn't.

The only time a professional player is usually injury-free is when he walks through the door on the first morning of pre-season training in July. By the second morning, you feel like your hamstring is hanging off, your groin seems tight and your big toe is sore. They are hazards of the job and only get worse throughout the season. Being injured is part of being a footballer. Roy Keane and Bryan Robson at United were always injured because they were hard-tackling, warrior-type midfielders, but only the most serious injuries would keep them out.

Keane used to complain that his knee was sore for years after his cruciate ligament operation. He played on. He had bad hips, too. He played on. He played through the pain, for which he had a high tolerance. And, like Robson, he was superb.

The bodies of many a former professional pay the price. Older players in the generation before mine have health problems, their knees shot to pieces by too many cortisone injections. Is it a price worth paying? It was for me, but maybe I was lucky, because my injuries weren't more serious.

Earlier in my career, I played through knee ligament pain at Bristol City because I was desperate to keep my place. I knew I'd need an operation at some point, but I wanted it to be after the season.

Kevin Keegan, the Newcastle United manager, was watching me at the time. He knew about my knee problem - a quick call to anyone at the club would have revealed that. There are few secrets in football.

But he still made me Newcastle's record signing and told me that he liked my attitude for being prepared to play through pain. Managers need their top players to play while injured. They won't acknowledge publicly that they are carrying injuries, information which would only allow an opponent to exploit a potential weakness. That's how it is.

I had real problems with an Achilles injury for years, but I played on and didn't always inform people at the club of how much pain I was in.

I would wake up in intense pain each morning and needed to warm my Achilles up for 30 minutes. I played through it until I had an operation … which, six months later, a doctor told me I didn't need.

Players are always at the risk of bad medical advice. The science is improving - but injuries are still a major part of a footballer's life. It's how you deal with them that matters and your mental well-being has a lot to do with that. I don't buy it that some players are a "sick note" because they don't want to play, more than their pain threshold is less than a Keane or a Robson. But reputations count for a lot and a manager needs to consider that when signing a player.

Football has changed at the top level, though. Bigger squads mean managers have more options. They can now rest a player who is only 70-per-cent fit and go for one who is closer to full readiness. That is not a luxury always afforded to players in smaller squads lower down, where players are needed twice a week, week in, week out.

Unless they have their own Ronaldo, who they just can't do without.

Andrew Cole's column is written with the assistance of the European football correspondent Andy Mitten.

[ sports@thenational.ae ]