On a brief visit to the UAE last month, the author James A Robinson lectured a largely rapt audience on the subject of "why nations fail". It was standing-room only in the hushed halls of Manarat Al Saadiyat when Robinson got up to speak, offering some proof that it's not just star musicians but social scientists who can pull big crowds to Abu Dhabi's outlying islands. Better still, the Harvard academic appeared on stage at pretty much the time he'd advertised.

Robinson was on a short stopover in the capital to promote his new book (co-written with Daron Acemoglu) on the origins of power, prosperity and poverty. The Review will carry a longer discussion of that book next week, but the main thrust of Robinson and Acemoglu's argument is to suggest that the world's economies and nations tend to be either "extractive" or "inclusive".

Extractive economies are, according to Robinson, those where the mechanisms and levers are set to ensure that the people in the seats of power extract the maximum out of the nation they preside over, and do so exclusively for the ruling elite's benefit. Inclusive economies are generally more empowering, offering citizens of that nation some stake in its future. Further, those that fall into the former category tend to fail, either in the long or short-term, while those in the latter are likely to prosper or, given today's choppy economic climes, are unlikely to fail.

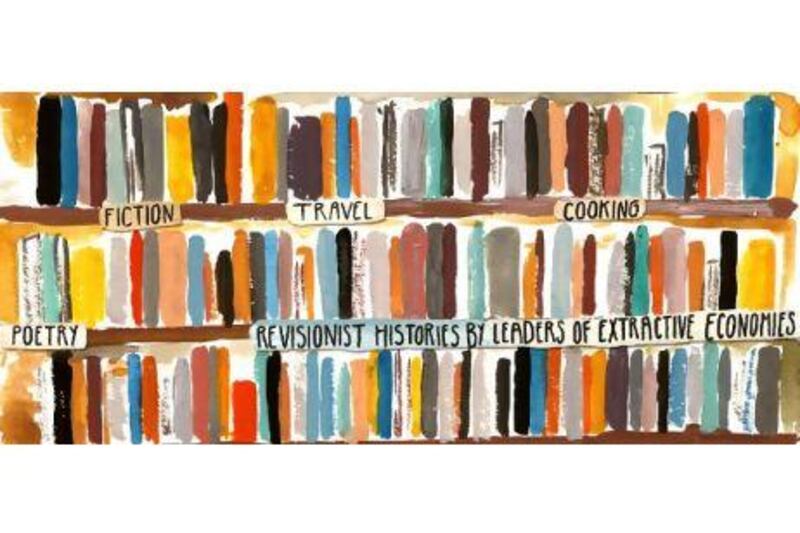

Robinson's theories came back to mind with recent news of two memoirs which might reasonably be placed in a category marked with the words "the literature of extractive economies".

According to a report on Al Arabiya's website, the handwritten memoirs of Saddam Hussein are currently being hawked around western publishers by Raghad Saddam Hussein, the fallen despot's daughter. In a separate development, Leila Ben Ali, wife of the former Tunisian ruler, has just published her autobiography in France through the Editions du Moment imprint.

That these memoirs are authentic seems beyond doubt - the provenance in both cases cannot come any higher, although some observers suggest that Ben Ali's book has been sculpted by no less a hand than her husband's - but what, one wonders, can either of these books expect to honestly add to the narrative of their nation's recent past? Apart, perhaps, from long descriptions of how tough it was to be trapped inside the gilded corridors of power. Or how everything they did was for the good of the country?

In truth, Saddam's memoirs are most likely to reveal the ramblings of a deluded and evil man, while in the case of Leila, the hairdresser whose clippers caught the ruler's eye, her book will almost certainly travel across some already familiar terrain.

Last year, Ben Chrouda, the couple's butler, published his own hand-washing memoir, which detailed how Ben Ali was infatuated with his wife, how Leila was manipulative and Chrouda himself was "just a butler" who happened to be caught in the wrong place as history beckoned.

Don't expect Leila to cast herself as remotely controlling in her own pages. Instead, she will undoubtedly emerge as merely "a devoted wife".

A more accurate account of how a dictator's wife might fill her time arrived by accident in March, when a series of emails purporting to have been sent by Asma Al Assad, the British-born wife of the Syrian president, leaked into the public domain.

The messages - which are almost certainly more compelling (and more awful) than any of the memoirs above - revealed that as Syria crumbled, Asma ordered kitchenware from Amazon and candlesticks from Paris. She spent as the nation simmered; she sought retail therapy as the country revolted; she was home-making as homes burnt.

In doing so, Al Assad validated Robinson's extractive-inclusive theory. One way or another, those who lack appropriate guiding principles will eventually reveal themselves as utterly bankrupt in every sense of the word.