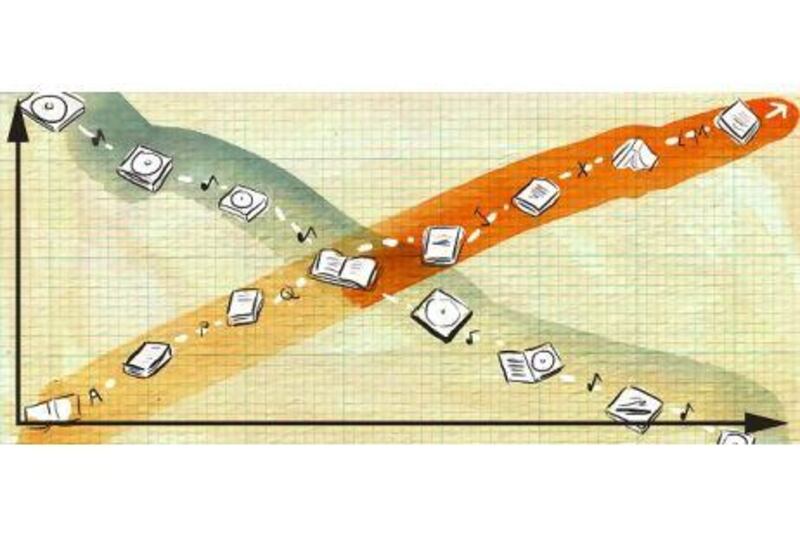

In Robert Levine's engaging 2011 book Free Ride, which was reissued last year, the author presents an unvarnished vision of what he rather inelegantly dubs "the culture business". Levine identifies "the culture business" as comprising the music, newspaper, book, TV and film industries, and believes all those sectors have been damaged by the ongoing online revolution.

He suggests that in the past few years, culture has been blighted by internet piracy, forcing the price of digital goods down to zero, with the result that there has been a "race to the bottom", not only in the amount of revenue and profit generated from cultural production, but also in the ambition and quality of the producers themselves. Why spend several months and millions of dollars creating a blockbuster movie, when a teenager in Tulsa can watch that same film for nothing via an illegal file-sharing website?

Uniquely, one of those sectors Levine references, the book industry, has battled some of the worst infringements of the digital age by being both ancient and modern at the same time: a printed book is an "old world" and trusted technology, never likely to run out of power nor find itself outside of network coverage.

Levine also later argues that the World Wide Web empowers the creative individual as much as it promotes unlawful activities. "Anyone can [now] create culture instead of simply consuming it," he points out. "It's never been easier to distribute creative work [but] it's never been harder to get paid for it."

Again, the book industry is particularly well represented by this last statement: the explosion in the number of authors self-publishing has, to some extent, broken down doors that were once locked, yet only a select few of those who self-publish will experience genuine success. For every Amanda Hocking there are several thousand hopeful authors who make barely a dirham from the books they write.

Generally, book publishers have also been reasonably adept at shoring up their revenue streams in the digital era: tablets are increasingly popular and, while piracy remains a constant threat especially in developing markets, there are fewer downsides to protecting an e-book with digital rights management software (and thereby avoiding duplication on an industrial scale) than there are for a record label surrounding its latest music release with similar protection.

As Tim Hely Hutchinson, the chief executive of one of Britain's largest publishers, put it to me recently: "If you wrap a piece of music in DRM it diminishes the audio quality, [but] you cannot tell the difference between an e-book that has been wrapped in DRM and a book that hasn't."

Nevertheless, the fit between digital and physical is not entirely perfect. If the pirates are being kept at bay, then how, for instance, will the bookseller fare in this virtual environment?

The online retailer Amazon has long been a thorn in the side of traditional booksellers - by being able to aggressively discount and by holding vast quantities of stock - but there are signs that some stores will make progress against the rising digital tide. And they will do so because they offer a decent customer experience.

Kinokuniya in Dubai Mall is one such local example. Occupying 68,000 sq ft of the mall and stocking more that half a million books, the store is breathtaking in scale. (By comparison, even the soon-to-close "World's Biggest Bookstore" in Toronto is smaller than Kino.)

Best doesn't have to be biggest either. The British retailer WH Smith has recently firmly planted its feet in this country and while its bookshelves are by no means comprehensive, they do offer a thoughtful selection of a few hundred bestsellers and new releases. Both retailers look nicely placed to survive the worst challenges to Levine's "culture business".