I have long held the belief that most post-match interviews would be improved immeasurably by gagging the participants, thus forcing them to communicate the usual dull cliches via facial expression and gesticulation alone.

So imagine my delight when Mark Allen emerged from a UK Snooker Championship match last week in precisely that state, with his mouth sealed by a four-inch strip of black gaffer tape.

"At last" I thought, "they have started reading my letters!"

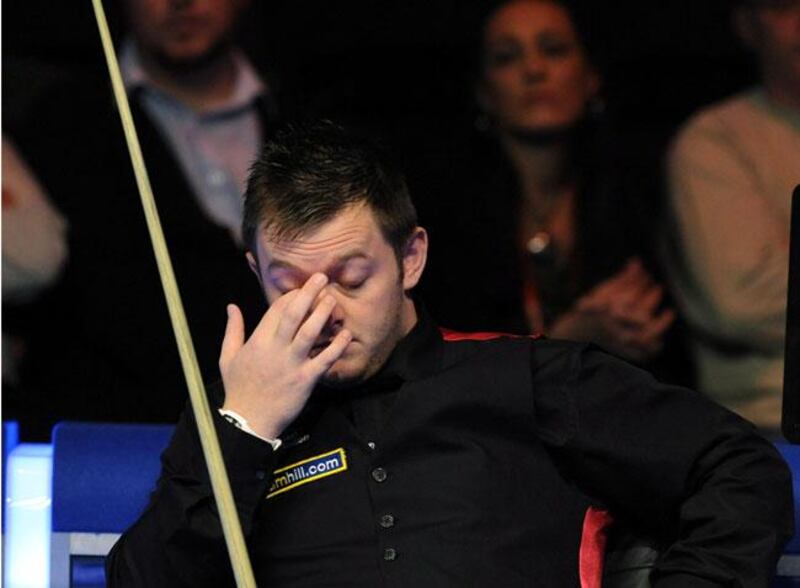

Sadly, it turned out to be temporary. Allen, who went on to make the final, which he lost 10-8 against Judd Trump, was making a visual protest at what he perceives as the censoring of players by the sport's governing body, World Snooker.

The Northern Irishman is unhappy at recent changes designed to jazz up the sport - notably the shortening of matches from a best of 17 frames to a best of 11 - and he said so in a foul-mouthed attack on Barry Hearn, the World Snooker chairman. He now faces disciplinary action for swearing, although he believes he is being targeted for speaking out.

Call me cynical, but my immediate reaction is to smell a rat.

Hearn is one of the canniest men in sport, with a long record of innovative public relations stunts. He was a driving force behind the 1986 Chas and Dave single Snooker Loopy, which was a record approximately three minutes and 20 seconds too long.

Hearn is a professional sports promoter. By definition, he knows how to drum up a crowd.

And for all of his tinkering with snooker - shortening matches, grandiose player entrances, the sheer lunacy of Power Snooker - Hearn surely knows that nothing sells sport like a bit of friction.

Fans love friction, whatever the sport. From John McEnroe to Muhammad Ali and Michael Schumacher to Eric Cantona, our most prized sporting icons were those who provided both artistry and argy-bargy in equal measure.

Even last week, as Fifa sought votes for its Puskas Award, which recognises the most beautiful goal of the year, far more media attention was devoted to Sir Alex Ferguson's amusing spat with Roy Keane, post-Champions League humiliation, and to Luis Suarez's offensive gesture towards home fans at the Fulham-Liverpool match.

Beauty is boring. All you can do is admire it. Friction, however, has far more to go at. Friction enables us to take sides, to spit venom, to shout at the radio. Friction is the gift which keeps on giving, and it is far easier to manufacture.

I have no idea if Allen's row with Hearn was cooked up from scratch, pre-planned like the traditional pantomime violence of a boxing weigh-in (another sport, coincidentally, which Hearn promotes, having represented spiky characters including Chris Eubank, Steve Collins and Prince Naseem Hamed).

But even if its origins are genuine, Hearn has done little to quell troubled waters. Even his apparent refusal to discuss the issue - "I am far too busy to worry about silly little boys making silly little comments" - seems designed to inflame, while his vow to sue for slander was a certain headline generator.

I have no problem with any of this, by the way, having long since made peace with my baser appetites. I just wish other athletes would follow Allen's lead in saying something interesting.

Otherwise, maybe they could borrow his gaffer tape?

LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION!

Enoch Powell, a late and not particularly lamented British MP, once remarked that a politician complaining about the media was like “a sailor complaining about the weather”.

But what about when a sailor complains about the media? Is that like a politician complaining about the weather?

Maybe we should ask Ben Ainslie, the triple Olympic gold medallist, who had a spectacular bust-up with a media boat at the Sailing World Championships off Fremantle in Australia on Saturday.

The British sailor had just finished the ninth Finn class fleet race when he dived off his own boat and climbed aboard a media vessel which he felt had impeded him, with a cutlass clenched between his teeth.

OK, there was no cutlass, but you suspect he would have liked one as he remonstrated with the driver and appeared to shove a cameraman.

His team denied any assault took place, but Ainslie was nonetheless disqualified for gross misconduct and effectively forfeited his chance of a medal.

Good. Professional athletes love to slate the media – and I fully support their right to fire back at snarky writers, pundits and armchair critics.

Film crews, however, should be strictly off-limits. Every time we marvel at a beautiful action photograph, insightful camera angle or the resonant crunch of bodies colliding, we should be thankful to the skilful souls who produce them, often in the face of hostility from fans and contempt or aggression from players.

The fact that they nearly always manage to achieve such quality while staying out of the way is a testament to their craft, so we should be a little more forgiving if they occasionally get it wrong.

“I’ve worked extremely hard over the past six weeks and have trained incredibly hard to get to this position,” Ainslie later fumed. He probably did but, without television crews, would that “position” have existed in the first place?