GILGIT, PAKISTAN // Representatives of Pakistan's tranquil Northern Areas, a tourism centre bordering China, have petitioned the government to revert to the historical name of Gilgit-Baltistan to distinguish it from areas plagued by militant insurgency. The five districts of the Northern Areas are situated amid the sky-scraping peaks of the Karakorum mountain range that divides the Indian subcontinent from Central Asia.

Isolated from the rest of the world until May 1978, when Chinese and Pakistani engineers completed the Karakorum Highway (KKH), the world's highest road route, it is a magnet for tourists drawn by the history of the Silk Route, an ancient trade link between China, the Middle East and Europe. Western tourists, in particular, are drawn by the districts of Hunza and Gojal, equated to the mythical kingdom of Shangri'la, made famous in the 1933 novel Lost Horizon by James Hilton.

However, domestic and international tourist numbers have slumped this year because of misperceptions about the proximity of Gilgit-Baltistan to Swat and tribal areas, where Pakistani security forces are fighting to reverse territorial gains made by Taliban insurgents since 2007. Hoteliers in Gilgit and Hunza said their businesses, which form the mainstay of the regional economy, have collapsed because of generalised diplomatic and media terminology which describes the insurgency-racked districts of the North West Frontier Province and tribal agencies bordering Afghanistan as "northern areas".

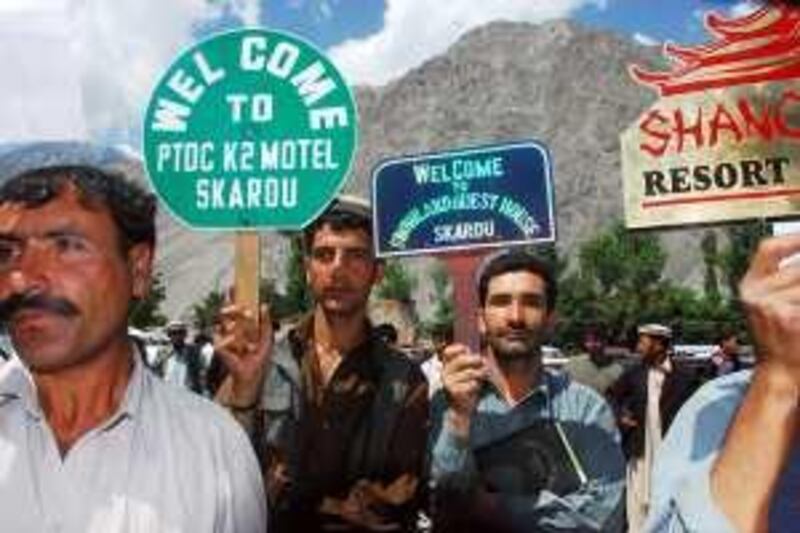

That, they said, has created an impression, both within Pakistan and overseas, that the Northern Areas has a security problem, whereas there had not been a single terrorist attack there until a paramilitary soldier was shot dead in Gilgit on July 25. The motivation for the attack is still unclear. "We are in the middle of the high season and hotels are empty. We are receiving just two per cent of the domestic tourists that visited by this time last year, and there hasn't been a single international tour group yet," said Shah Jehan, vice president of the Northern Areas hotels association. The first foreign tour group, from Spain, was seen in Hunza.

In fact, Gilgit-Baltistan is separated from Swat by 300 kilometres of impassable high altitude desert, connected to mainland Pakistan only by the KKH, while the tribal agencies are on the other side of the North West Frontier Province. An attempt in April by the Swat Taliban to expand northwards into Kohistan district, which forms a 100km buffer along the KKH, was decisively defeated by hostile tribesmen in three days.

"That is the upside of having such limited road communications with the rest of Pakistan. The Taliban could not reach here, even if they wanted to," said Rehmat Nabi, the president of the local tour operators association, which has formally applied to replace its existing Northern Areas prefix with Gilgit-Baltistan. The residents of the region are a distinct ethnic group who have more in common with the Turkic races of Central Asia than the Pashtun tribes of the Talibanised areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

There is little appetite for the puritanical version of Islam propagated by the Taliban and its al Qa'eda allies: the population of four districts out of five in Gilgit-Balistan is dominated by the Shiite, Ismaili (followers of the Aga Khan) and Sufi Nurbaskhi sects, according to local journalists. "My home district of Chilas is the only Sunni area and the people there have taken a collective decision to ensure there is no terrorist infiltration. We have nothing in common with them and want nothing to do with them," said Farooq Ahmed, a journalist based in Gilgit.

Such strength of feeling about being tarred with the Taliban brush in April prompted the Northern Areas Legislative Council, the region's elected assembly, to unanimously pass a resolution, calling on the Pakistan government to change the constitution to facilitate the change of name to Gilgit-Baltistan. It has since been grouped with a wider package of political reforms soon to be unveiled by the federal government, Mr Ahmed said.

However, local stakeholders fear political apathy in Islamabad, the capital, will delay the process for the rest of the 2009 tourism season, which ends in December, and fail to address public misperceptions about the region in time for next year. They point to the fact the ministry of tourism has since December been headed by a cleric from the Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam religious party, a coalition partner that, in collaboration with Pakistan's intelligence agencies, groomed thousands of recruits for the Afghan Taliban in its 1990s heyday.

Hoteliers in Karimabad, the tourist capital of Hunza, said the government, by turning the ministry into a political sop, had practically, if inadvertently, guaranteed that there would be no effort to support the region's failing hospitality industry, a major source of employment, particularly for the emerging generation of educated young people. "By showing how little it cares about our image and perception, the government has killed off business and delayed some major projects, including the region's first five-star hotel, and that has made a lot of ordinary people very upset," said a hotel clerk, who requested anonymity because he was not authorised to speak by his employers.

thussain@thenational.ae