Uzbekistan is a fascinating central Asian country with a history that spans the opulence of the Silk Route through to the current environmental disaster of a barren Aral Sea, says John Henzell

Travelling to the most famous cities of the Silk Route has always required a degree of forbearance, but modern-day visitors can at least expect a much warmer welcome than many of their predecessors received.

In the fortress city of Khiva, tea is now served in the former slave market where hundreds of Russian settlers were sold into servitude after straying into areas controlled by Turkmen tribes. In Bukhara, the vermin-infested pit where two British officers were jailed then beheaded – they failed to show appropriate deference to the ruler – is now part of a museum. And in Samarkand, the gilded city razed by Genghis Khan’s raiders then rebuilt by Tamerlane to become the most famous Silk Route city of them all, a slightly shifty middle-aged man will wait until you’re alone then sidle up and ask: “Hey, do you want to climb the minaret?”

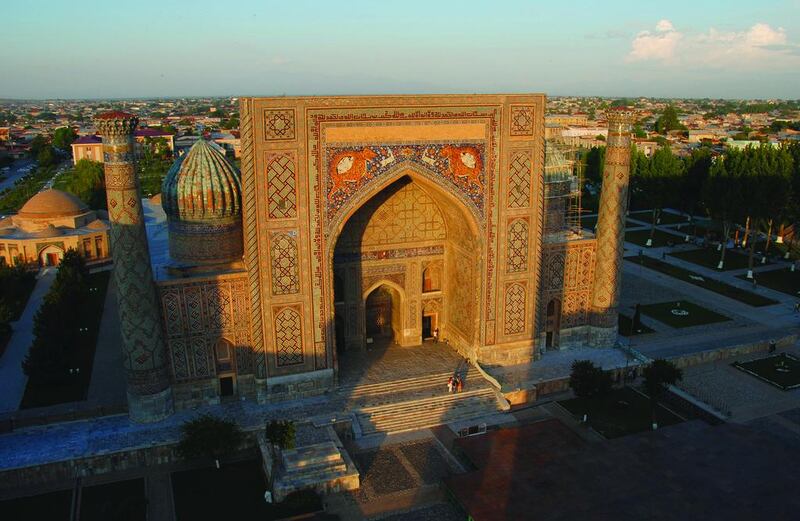

In return for a small denomination US dollar note, I was able to scramble up a tiny spiral staircase to the highest point of the Registan, the historic heart of Samarkand. Below me are the elaborately tiled facades of the three madrasas built around a central square by Samarkand’s rulers over a span of 250 years to create what was once one of the foremost places of learning in the world.

At a time when Europe was just beginning to emerge from the dark ages and the Islamic world was in the midst of its golden age of science and discovery, these were the Harvard or Oxford of their time – places to come to learn about everything from engineering to astronomy, medicine to architecture and Persian poetry to religious theory. Everything in front of me was because of the Silk Route, which was always far more than simply a conduit for trade between China and the Mediterranean. It was also for sharing ideas between east and west.

Of the dozens of city-states that became wealthy from the Silk Route, most are mere shadows of their former glory, having been either abandoned entirely after the Mongol raids of the 13th century, flattened by earthquakes or simply faded into decrepit obscurity. Through the vicissitudes of fate, Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva – the three best-preserved Silk Route cities – are all in Uzbekistan and each has a distinctly different character.

The most famous and also the most accessible to tourists is Samarkand, with the Registan’s three madrasas dominating a public square which was the place for everything from royal proclamations to public executions. Samarkand was once famous throughout the known world, having enthralled Alexander the Great in 329BC, but that phase of its existence ended abruptly when it was razed by Mongol hordes in 1220.

The Samarkand that enchants people today hails from when Tamerlane rose up against Mongol rule in 1365. One of his successors, Ulugh Beg, exemplified the golden age of Islamic learning by being not just a sultan but also a noted astronomer and mathematician. He built the first of the Registan’s madrasas in the early 1400s, setting the tone with a lavish tiled 35-metre high facade flanked by two minarets, behind which is a courtyard formed by a double storey gallery of lecture halls and students’ rooms.

Two more equally lavish madrasas were built 200 years later to frame the Registan’s square. Generally the centuries had not been kind to buildings like these, and nearby the once equally decorative Bibi-Khanym mosque has lost most of its tiles and other forms of decoration and is so riven with gaping fracture lines from earthquakes that it seems unwise to venture inside, which in any event is just an empty shell.

It turns out the Registan, like many an ageing beauty, has had some help along the way. There is plenty of debate about the legitimacy of this, best demonstrated by the spurious addition during the Soviet era of a mammoth blue-tiled dome to one of the madrasas.

Less controversial but still contentious is the very recent repainting and regilding of the interior of some of the madrasas, so what travellers see now is exactly as lavish and opulent as had been the case when it was first built, albeit at the cost of the patina of age.

I moved on to Bukhara, an oasis town in the rolling steppe to the east and to which Samarkand’s rulers began shifting their attentions in the 1500s, prompting the latter’s slow demise and eventual abandonment. Bukhara also became famous as a centre of learning, with more than 100 madrasas and 10,000 students. It was also seen as the holiest city in central Asia, with 300 mosques.

And unlike the museum-like sterility of Samarkand’s historic heart, Bukhara’s old town was still lived in, with a series of covered markets in domed arcades – albeit aimed squarely at tourists rather than locals – and with family homes amid the monuments.

Most of the madrasas have collapsed in earthquakes or are being used as carpet showrooms or even as storage. But one, the Mir-i-Arab madrasa, is still a working religious school, having been established by a Yemeni sheikh in the 1530s. Tourists are not allowed behind its exquisitely tiled facade. Opposite is the Kalon Mosque, a vast building capable of holding 10,000 worshippers in the central courtyard or in the cool and quiet whitewashed vaulted corridors flanking it. It became my favourite building in Bukhara, with tapchans (the central Asian version of the majlis, except raised off the ground) where you can recover from the endless sales pitches from merchants trying to sell suzanis, the embroidered shawls for which the city is famous.

After Bukhara’s golden age waned with the declining Silk Route traffic, it became infamous for entirely different reasons. A British officer, Charles Stoddart, arrived in Bukhara in 1839 without bringing gifts or showing other signs of deference to the ruler, Nasrullah Khan, who threw him in jail. Another British officer, Arthur Conolly, was sent to secure his release but joined Stoddart in jail. In 1842, the pair were later publicly beheaded in front of the Ark, Bukhara’s fortified citadel, after digging their own graves. Now visitors can see the vermin-infested “bug pit” in which the two men spent the final years.

Khiva, the third of Uzbekistan’s Silk Route cities, is more difficult to get to and in turn receives far fewer visitors than the other two. Still, it was easily my favourite, feeling the most like a place where real Uzbeks lived, loved and laughed, rather than an open-air museum. That was despite also being geared for tourists, including a series of scheduled folk dances performed in the Inchon Kala, the walled old city. In most places I’ve seen these around the world, the entertainers usually look jaded, clearly more focused on payday than performing. Here they seemed like they were doing this for each other, oblivious to the outsiders who happened to visit.

Most of the city wall was still intact and within were a series of palaces, madrasas and mosques, most open to the public, but also just average family homes. Near the eastern gate, there was a caravanserai which was once home to central Asia’s most famous slave market, selling anyone unfortunate enough to be captured by ranging Turkmen or Kazakh tribesmen.

The desert in the north of Khiva seemed an unlikely place for tourists but is home to two entirely different but equally fascinating sights. The first was in the unlovely Soviet city of Nukus, which was far enough away from Moscow’s attention for art lover Igor Savitsky to secretly acquire tens of thousands of examples of avant-garde art banned by Stalin. Museums usually bore me but this one is worth a visit to Uzbekistan on its own.

Two hours farther north again is the town of Moynaq, which you feel – in the form of stinging clouds of salty dust – long before you see it. The salt is blown from the bed of what was once the Aral Sea but which is now a byword for environmental disaster on an apocalyptic scale. Once Moynaq was a thriving fishing port but years of overextraction of the Amu Darya River has seen the shoreline recede 180km to the north, leaving the fleet of fishing boats stranded eerily in the dunes. Now the town feels like it is following the Aral Sea towards oblivion.

A former fisherman gave me a tour of the stranded boats – some up to 30 metres long – and the scene’s emotional effect on him hinted at the human cost of this environmental devastation. Once these were a symbol of the locals’ hopes and dreams but now they just remind them of all that they’ve lost.

jhenzell@thenational.ae