There's not a flicker of emotion on his big, broad face. His cheeks and forehead are covered almost entirely with hair, each strand thick, coarse and jet-black. His unblinking eyes, dark and moody, are aimed squarely in my direction, with an unwavering intensity that causes my knees to wobble. Intimidated, I look away sheepishly. A staring contest with a 200-kilogram silverback gorilla is not one that you're likely to win.

I'm deep in the jungle-swathed peaks of south-west Uganda, an area that is home to more than 400 mountain gorillas – a dozen of which are sat just a few metres away, staring at us as we stare at them.

The junior members of the Rushegura family lighten the mood, somersaulting from the treetops and landing on the ground with heavy thuds. Mwirima, the silverback, the burly patriarch of the group, looks on with an expression shared by exasperated parents the world over. He crunches on thick sticks of bamboo and grunts loudly.

Tracking wild mountain gorillas is quite the adrenalin rush. Every year, thousands of travellers descend on this small corner of central Africa in the hope of seeing these iconic and critically endangered creatures in their natural habitat. Of the estimated 880 that remain in the wild, half are found in Uganda's Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, with the rest residing in neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda.

But unlike other African wildlife – most traditionally seen from the comfy confines of a jeep – spending time with these primates in their domain is a journey that should not be entered into too lightly.

Constantly on the move in search of fresh grazing, locating them requires strenuous trekking through humid jungle and, at times, along steep mountain ridges to altitudes of 2,000 metres. Impenetrable by name, impenetrable by nature: hiking in Bwindi is a challenge.

"It's tough, but seeing the gorillas is virtually guaranteed. I've spotted them within 20 minutes of setting off, but it can sometimes take five hours or more," says our guide Mathias, an hour into a sweaty hike. Up ahead, park rangers with rifles clear the overgrown trail that's scattered with rainbow-coloured butterflies and large snails with beautiful shells. I scan the treetops for chimpanzees.

As well as the significant physical investment, tracking gorillas also incurs substantial costs. Seeing these gentle giants doesn't come cheap. Highly sought-after permits are required and must be obtained in advance. A maximum of 64 are issued per day with each costing US$500 (Dh1,837): a fee that goes toward gorilla conservation, the upkeep of Uganda's national parks and aiding the local community.

While the cost of permits in Rwanda has recently increased to an eye-watering $750 (Dh2,755), the Uganda Wildlife Authority has, for the first time, introduced savings of $150 (Dh551) per permit for three selected months in 2014.

Protecting the gorillas is paramount. Groups are limited to a maximum of eight people and time with the gorillas is strictly limited to one hour. But that's not all. Long before any tourist can get close, each gorilla family undergoes an intense, two-year period of habituation to ensure that they are comfortable with human company and safe to be around.

"No tourist has ever been harmed by a gorilla," says Mathias, reassuringly. "But they do sometimes charge. It's happened to me. A silverback once stopped so close to me that I could smell his breath."

The world has been intrigued by these enigmatic creatures – which share 96 per cent of their DNA with us – since a German army officer stumbled upon them in 1902 while out mountain climbing.

In a country as troubled as Uganda, gorilla tourism is something to applaud. It's an African success story that has transformed an impoverished area and saved the iconic creatures from extinction. While the gorillas themselves were never hunted, they would often fall victim to traps left in the forest for other animals, meaning that numbers plummeted.

Poachers have since retrained as guides and porters; others have sought work in the numerous camps and lodges; and many sell primate paraphernalia along the town's dusty main street. Nearly all have benefited, but not everybody is celebrating.

Conservation in action spelt eviction for the nomadic Batwa tribe, which once lived deep within the mountains. Considered to be the very first inhabitants of the area – settling thousands of years ago – this indigenous community were forced out with the proclamation of the national park in 1991. Without compensation, land of their own or work skills, they struggled to integrate with society and became some of the most marginalised people in the world.

Their fortunes changed in 2000, when an American doctor named Scott Kellermann visited the area. It was a trip that proved as life-changing for him as it did for the Batwa.

Moved by their plight, Dr Kellermann later relocated to Uganda and set up a foundation to help the displaced tribe. Today, many of the Batwa have permanent homes on specially acquired land on the outskirts of the park, in addition to health care, education and employment.

Despite such developments, many remain bitter over their removal from the forest and fear that their ancient customs are in danger of being lost forever. So, in a last-ditch attempt to keep their traditions alive for future generations, the community set up an interactive preservation project.

The Batwa Experience originally started as a way to educate the tribe's children about their roots, but has grown substantially and now welcomes curious visitors keen to learn more. I'm one of them.

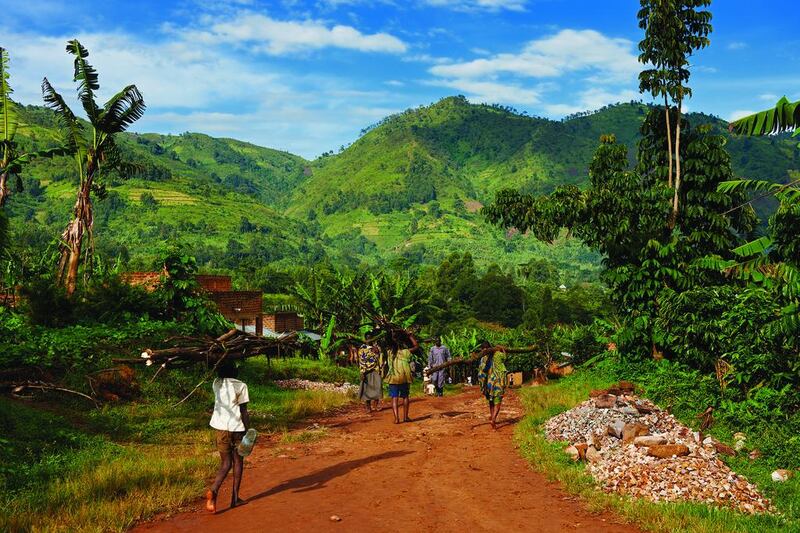

I meet the guide Eliphaz under a century-old fig tree beside the primary school in the nearby village of Buhoma. Cattle graze on the grass and children sneak out of class to play in the sunshine. Women returning from a morning ploughing the fields cross the unpaved paths. One, dressed in a full-length scarlet gown, walks slowly, with a rusty axe slung over her shoulder and a large sack of maize perched on her head.

During the hour's walk to the Batwa, a pleasant stroll through tea plantations and banana groves, Eliphaz and I discuss their plight. "Things have changed a lot. More than 150 families now live in small brick houses, but some don't want them. They complain that they're too big and too modern, that the rain makes a noise on the iron roofs and that they want to return to the forest."

The trail gradually rises, revealing sweeping views of verdant valleys below. Before long, voices can be heard among the trees and several members of the Batwa appear.

Pint-size (the average height of the Batwa is just 1.2 metres) and wearing traditional clothing of frayed ochre-coloured garments made from tree bark and decorated with cowrie shells, they sing and yelp in a traditional tribal greeting.

Among them are the elders Brangirama and Barekwe, who also answer to James and Flora (presumably for the benefit of foreign tongues). Together, we walk in the hushed highlands with James hacking at medicinal plants with his machete while his fellow tribesmen demonstrate how they once hunted, made fire and built tree houses.

Lunch is a hearty bowl of matoke – cooked bananas served in a pinkish paste made from grounded nuts. Talk turns to the past and the future. With Eliphaz translating, James speaks solemnly. "Our culture is dying in every way; our religion, language and ancient ways have almost gone completely. I pray we can one day return to the forest," he says, raising his clasped hands to the sky. A small yellow butterfly flutters past and lands on his bald patch.

Flora breaks the silence. "I am very sad inside. It's good to protect the gorillas, but what about us?"

I wonder whether the tribe had ever feared living alongside such powerful and unpredictable neighbours. "No, never," insists James. "The gorillas were like our brothers. They would sometimes come and steal our honey. Occasionally, they would charge, but we knew how to handle them. The trick is to raise your arms and shout."

Female members of the tribe, it transpires, had an alternative method. "We would simply reveal our breasts and the gorillas would run away," says Flora, matter-of-factly.

I consider sharing this information with the female members of my gorilla trekking group the following day, but decide against it. The route is treacherous and slippery. We follow muddy trails, limbo under spaghetti-like vines and cross fast-flowing rivers with algae-covered rocks.

Mathias's radio crackles with news that the trackers up ahead have located the gorillas and we soon reach the place that we have all come so far for.

The Rushegura gorillas are all around us, though Mwirima, the silverback, was nowhere to be seen. It was Mathias who eventually spots him, way up high in the misty canopy, perched on top of a mossy hagenia tree.

It shook violently as the giant gorilla nimbly made his way down. "Stay still and stay calm," whispers Mathias. Mwirima rushes past, hunched over on all fours and almost close enough to touch, before slumping to the ground and revealing his grey-speckled back.

In jovial scenes, baby gorillas beat their chests with both hands and an adolescent female hangs from branches overhead. She swings back and forth, gazing down at us quizzically as though she is the one on safari.

All the while, the placid Mwirima sits deep in thought. He studies his fingernails and rubs his chin with hands that could smash through walls.

As the end of our hour approaches, he turns and our eyes meet across the forest. His nostrils flare with every deep breath. The moist air seems to thicken and all I can hear is my pounding heart. But this time I hold his gaze. There's a kindness in his eyes, as though we have his blessing to briefly enter their most extraordinary world.

weekend@thenational.ae

Follow us @TravelNational

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.

On the trail of endangered gorillas – and people – in Uganda

Nick Boulos treks in the Ugandan jungle to track the central African nation’s endangered gorillas, but finds the area’s indigenous Batwa people, initially excluded from their land, equally fascinating.

Editor's picks

More from The National