Joseph Conrad once said: "It is well known that curious men go prying into all sorts of places (where they have no business) and come out of them with all sorts of spoil. This story (Heart of Darkness), and one other...are all the spoil I brought out from the centre of Africa, where, really, I had no sort of business."

It was an honest admission of quasi-colonial intrusion from a writer who was a master of different perspectives, and who navigated the often over-simplified terrain of colonised and coloniser.

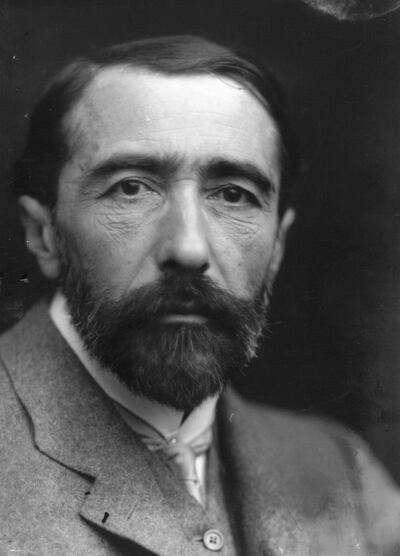

At a talk at the NYU Abu Dhabi Institute this week, the American academic Maya Jasanoff recounted Conrad's extraordinary life, by way of an introduction to her new book The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad in a Global World. "As an immigrant from Poland to England, and in travels from Malaysia to the Congo to the Caribbean, Conrad navigated an interconnected world, and captured it in a literary oeuvre of extraordinary depth, argues Jasanoff. "His life story delivers a history of globalisation from the inside out."

Jasanoff, who has herself travelled to some 70 countries and was born to an Indian mother, argues that Conrad was a "prophet of globalisation as we recognise it today", in that his works, which included Heart of Darkness, published in 1902, and The Secret Agent (1907), dealt with the still-pertinent issues of migration, global capitalism, nationalism, terrorism and imperialism, as well as the challenges brought by technological change, such as those in the shipping industry, which speeded-up transit times and saw skilled humans replaced by machines.

"The world of 1900 was very like today, in that it saw a step change in the scale and pace of globalisation," Jasanoff said, and some of Conrad's 100-year-old narratives are uncannily familiar. The Secret Agent features a bomb blast in London and shadowy Russian influence; Lord Jim involves incidents in global shipping, from the Red Sea to Asia, and Nostromo was about South American politics, mining, capitalism and revolution.

“It was a world of connections, but Conrad sees past apparent binaries and offers narratives from a non-colonial perspective,” Jasanoff adds. Much of this, of course, came from Conrad’s own international background, in which he was born in what is now Ukraine to Polish parents, moving to Warsaw as a child before the family was forcibly ejected to Siberia.

After being orphaned at the age of 11, Conrad spent most of the rest of his life on the move, travelling through France before landing in Britain penniless and becoming a sailor. “The maritime world was hugely international and open to people on merit, but at the same time, he saw how this regime of free trade and imperialism was not accounting for their needs,” says Jasanoff. “Conrad questions ideas of progress and make us look at how individuals get caught up in forces outside themselves, and asks where our roles and responsibilities lie.”

Conrad's ability to offer so many multiple perspectives came from his status as an exile and expatriate, combined with his family's political background. Rising to the position of captain, he travelled the world both on and off ships for about 20 years, with what he learns in one country informing what he sees in the next. Particularly powerful is Heart of Darkness, about European colonial exploits in the Congo, which at the time were sold as positive and civilising, but in reality were sickeningly brutal. It was only by going there – in his case as captain of a steamer ship for a Belgian trading company on the Congo River - that Conrad could have so effectively lifted the lid on wilful nationalistic propaganda.

Ironically, Conrad’s later works, produced when he was comfortably settled in England, achieved little success. It was Conrad’s multi-dimensional narratives, borne of travel, which make us question whether there is one simple force at play in any situation, and if there is one single conclusion.

Ending her talk on a hopeful note, Jasanoff says that we can take note of the failures that come of using narrow national and political terms to define people and see the benefits of the post-national, or transnational world we are in. “Polarities can be transcended and we can try to beat back our reductive tendencies and fracturing impulses. History has many examples of people co-existing successfully.”

Just travel, she might have added, and you’ll begin to see it.

__________

Read more:

[ On the move: time travel through new translations ]

[ On the move: a brief moment of brilliance ]

[ On the move: how to be a travel writer ]

__________