It’s a five-and-a-half-hour direct flight from Dubai to Myanmar, which sits between India and Thailand.

You fly into Yangon International Airport and straight into a colonial hangover – the airport code is RGN, short for Rangoon, the British name for the capital of the country they called Burma. Now Burma is Myanmar and the capital is Naypyidaw, though Yangon, with a population of more than five million, is still by far the biggest city and commercial centre.

The airport has a new terminal and runway, but parts of it are still being finished; most of the shops and concourses are eerily empty. Meanwhile, a bigger airport with a much larger capacity is being built many miles out of town. Some might sense a theme here.

Naypyidaw, 322 kilometres north of Yangon, was built on a vast scale by the country’s former socialist-military government. A huge and bizarre Stalinist-style political centre with identikit government departments and empty eight-lane motorways, it officially became the capital in 2005.

“Naypyidaw means royal palace,” says Cherry, my local transfer guide who takes me through the airport. I ask her if the project may be abandoned now that, as of this year, the National League for Democracy is in power. “No,” she says. “That’s their kingdom. It’s away from the people and the traffic. They won’t want to move it back.”

Cherry, like most local people I meet here, speaks candidly about politics, albeit with a knowingness that betrays the sense that despite real change on many levels, old structures die hard. Still, it seems somewhat amazing and pleasing that after so many years of campaigning, the first democratic elections in decades have been held here, and that without violent overthrow, Aung San Suu Kyi, the NLD’s leader, is now the country’s de facto leader. Change, it seems, accelerated after the Nobel laureate was released from house arrest in 2011. Most western sanctions have been lifted, as has a mostly western boycott of tourism to the country.

Yet driving into the city with a guide from the travel company Belmond, a younger-than-he-looks 40-year-old called Brian, there’s ample evidence that despite western sanctions, the business of trade hasn’t stood still. Modern shops, offices and hotels line the main road into town – it’s not Bangkok, but it’s more developed than many parts of India, Sri Lanka or Bangladesh. ATMs are plentiful, as is Wi-Fi. “Our main trading partners now are China, India, Japan and South Korea,” says Brian, explaining that since restrictions and tariffs on car imports were loosened, Yangon’s traffic has become much worse – now averaging 12kph.

Though average salaries are still very low – the minimum wage in Myanmar is just US$2.80 (Dh10.2) for an eight-hour day – many more can now afford cars or motorbikes, and mobile phones. “Sim cards used to cost several thousand dollars,” Brian says. “In 1999 it was $4,000 [Dh14,690] for a phone with a sim card; only government cronies could afford them. Now they are a few dollars each.”

In the same vein, he says: "Before 2010 we didn't talk about politics in public places – only at home. Restaurants and cafes were full of secret police and even students were carted off to prison." And with that I'm dropped off at the Belmond Governor's Residence in the old embassy district.

A 1920s mansion built mostly of wood, the building was previously used as a city residence for the ruler of Myanmar’s southern states. Now a sultry hotel with 49 rooms and suites, it has tropical gardens, veranda-style restaurants and strong whiff of history. It’s the ideal base for a first-time trip here – its polished teak floors, comforting beds and perfumed air are a welcome contrast to downtown Yangon’s scramble of uneven pavements, open drains and decaying monuments. I’m particularly impressed when just minutes after putting a request in to housekeeping, a pair of brilliantly firm pillows are delivered to my room.

The next morning, after a decadent breakfast of fresh mango, Shan yogurt and mohinga – a spicy fish-based noodle soup – Brian takes me on a walking tour of Yangon’s downtown area. While at first glance it’s not an attractive city, I’m immediately struck by the scale and grandeur of some of the colonial buildings. Original features protrude from beneath the peeling paint, weeds and cracked windows of huge Victorian and Edwardian structures built to house government offices, the railway station and multi-use workshops.

"Colonialism made us beautiful," says Brian, not mentioning that colonialism also dragged the city into the Second World War and significant bombing by the Japanese. Though some are in such a poor state of repair that they look abandoned, Brian explains that many of the buildings are still functioning, though most are in need of thorough and inevitably very expensive renovation and restoration. In relatively good condition is the post office, dating from 1908; the historic Strand Hotel on the waterfront is one of the few full restoration projects; other, smaller success stories include the Rangoon Tea House on Pansodan Road, where we have lunch. Co-founded by British-Burmese Htet Myet Oo, it's a hipster-style cafe-restaurant-concept store, with high ceilings, whirring fans and a small creaky wooden staircase leading up to it. The menu would not look out of place in Shoreditch or Brooklyn; there's tea-leaf salad, Myanmar's tasty national salad made out of pickled tea leaves, diced tomatoes, shredded cabbage and nuts, banana blossom with chicken, mutton chops and chilli chicken. With prices from about $3 (Dh11) per dish, it's both good and wholesome.

“Many of the travellers who come here have eaten street food in Thailand, Vietnam and elsewhere in South East Asia and been fine with it, but in Myanmar they all get sick,” Htet says; that’s unlikely at this place. There are also 16 different combinations of black tea, with exact measurements of tea, sugar and milk.

So comfortable do the travellers and expats look here, that one wonders how popular this place could become. At the moment, one thing stopping a mass movement of foreigners to Myanmar is the shocking state of the housing stock – so decrepit are most of the houses and flats, and so limited are their number that quality serviced apartments in secure developments can cost $7,000 (Dh25,000) per month for a single small unit. I’m visiting in low season, during the wet summer period, but in the short peak season, from October to March, hotel reservations should be made months in advance.

We look around the large Central Market, which dates from 1926 and sells mostly fabric, clothing and gems. I buy a couple of ready-made longyis for 7,000 kyats each (Dh3 is worth 1,000 kyats), before heading to the city's most popular attraction, the Shwedagon Pagoda, which covers 46 hectares of land north of the downtown area. A 100-metre-high gold-plated stupa surrounded by smaller pagodas, it's the most sacred Buddhist site in Myanmar, a country where 89 per cent of the population follow its Theravada school.

As with all sites, visitors must leave shoes and socks at the door, and cover arms and legs. It’s a beautiful sight, especially against dark clouds, and the well-maintained, intricate and striking nature of the structures gives it an almost Disneyland-type appeal.

Brian tells me that because I was born on a Wednesday afternoon, my Burmese zodiac sign is an elephant without tusks, that my ruling planet is Rahu, said to be an invisible planet which is the enemy of the Sun and the Moon, which makes me a “contradictory, private and successful person”. Pilgrims and visitors may, if they wish, make offerings to their particular zodiac-dictated shrines, which are dotted around the base of the pagoda (it’s not possible to climb it).

Next, north of Inya Lake (the city's scenic artificial lakes were built by the British because the city had no water supply) we visit the Kalaywa Monastery, home to more than 1,300 shaven-headed young monks who learn scripture and collect alms. Apparently, many of the monks come from conflict areas or poor families, so it appears to be as much a homeless shelter as a school, though an atmosphere of discipline is palpable.

Far from the austerity of the monastery, that night we have dinner at Port Autonomy, another trendsetting restaurant in the former Australian ambassador's residence in the Bahan district. Here, American chef Kevin Ching and local property developer Ivan Pun have created a sensational pan-Asian menu that's worth travelling for (they've also opened a Vietnamese hipster restaurant downtown, called Rau Ram).

The restaurant is industrial chic inside, with a more sedate garden setting outside. On the menu, which has dishes from about $8 (Dh29.3), are scallop ceviche tostadas – an exquisite combination of Hokkaido scallops with avocado, coriander and lime, Burmese glass-noodle salad with tamarind vinaigrette, soft-shell crab with green papaya and pomelo salad, kimchi and mushroom quesadillas and manila clams in a miso and kimchi chowder.

Chan tells me that the current wave of creativity in the city is coming from “repats” – people who’ve gone abroad and brought bright ideas back. “Right now Yangon is a laboratory, and people come here to try new things.”

There's more evidence of this, and more surprising and sensational food to be found nearby the next day when I visit Sharky's, a western-style deli and cafe, for lunch. Started by U Ye Htut Win, the son of a Burmese diplomat who has lived in countries including Britain, Italy, Jordan, Sri Lanka and the UAE and who has returned after 20 years living in Switzerland, it offers European-style quality foods made in Myanmar.

From air-dried beef to fresh meat, gourmet cheeses, salads, breads, pastas, pizza and ice cream, the business has taken off in the past three years to the point where it’s struggling to meet demand from hotels and restaurants. I try a few dishes, but my favourite is a cheese board with unctuous Camembert laced with truffle; creamy, rich, buffalo mozzarella; and a pungent blue cheese, served with fresh bread and relish; the coffee is also excellent. A three-course lunch costs about $20 (Dh73.5) per person.

Just 10 days before a 6.9 magnitude earthquake strikes the area damaging several hundred of Bagan’s thousands of temples, I board an Air KBZ flight north to Nyuang U, the gateway to Myanmar’s biggest tourist draw, the old capital city of the first Myanmar Kingdom. Despite the shabby feel of the domestic terminal in Yangon, the flight departs exactly on time and is smooth. About half of the passengers are western tourists, and I’m dismayed to see that many have ignored responsible tourism guidelines on behaviour and dress, with many scantily clad to an extent that is indecent to local people. I’m seated next to a smart Chinese engineer working for an oil company, but there’s not much time for conversation before we descend over the Irrawaddy River, which has burst its banks, leaving dozens of homes marooned.

I see a few dozen of the estimated 2,500 stupas, pagodas and monasteries before we land, and it’s already clear that this is an exceptional site. Dating from the 10th to the 14th centuries, some of the mostly brick-built buildings are 1,000 years old. The site covers an area of 13km by 8km, and the buildings are in various states of repair and renovation.

One of the reasons Unesco has yet to declare the whole site a World Heritage Site is concern about the nature of the restoration, and inappropriate development there. Yet, while there is an ugly hotel, viewing tower and museum, I’m pleased to see that most of the area is still blissfully rural.

My hotel, the new Bagan Lodge, is situated between the small airport at Nyuang U and "new Bagan", a settlement created in the 1990s after locals were forcibly moved from the old centre. The main temple plain starts just across the road from my hotel, and after checking in I take a short walk around some of them before sunset. There's no fence or barrier, but all tourists must pay an entry fee on arrival at the airport. This makes the process of visiting more organic and atmospheric; I have all the temples that I see on my walk to myself. As the Sun sets, their darkly spiky silhouettes against a clear night sky are quite unearthly.

The hotel, in contrast, is a smart collection of more than 80 brick-built safari-style villas, with two pools and a spa, but because of the heat of the plain – daytime temperatures while I’m there are about 30°C during the day – the spacious air-conditioned rooms and standard of luxury is more than welcome. Multiple, fast Wi-Fi networks are also surprising.

At 8 o’clock the next morning, I’m collected by my guide, Tin Maung Swe, who will first take me on a bicycle tour. We set off from the hotel, pedalling first through nearby New Bagan – more of a village than a town – to the Lawkananda Pagoda, an exquisite gold pagoda overlooking the river. Swe tells me that this year the river has “overflooded”, leading to many people having to abandon their homes – global warming, possibly.

There’s a festival going on with a local market selling clothes, food and piles of wood that are ground up to make panakha, a natural form of make-up and sunscreen. Then we cut through a monastery and are immediately surrounded by fields studded with pagodas. Singing rings out from the town as we bike down a dirt path, the peaceful landscape looking like an Asian Oxford or Cambridge in medieval times. Fields are being tilled by ox-cart, and birds are singing in the flowering acacia and desert scrub trees.

There aren’t many other visitors, and, thankfully, foreigners aren’t allowed to rent motorbikes, but are permitted to hire Chinese electric scooters, for about $8 (Dh29) per day.

Because there are so many temples and pagodas, Swe has selected about 12, which he thinks offer the best views, architecture and history. Dhammayazaka Zedi looks a bit like a Mayan pyramid, with a stupa-like structure on top. We climb up the steep front steps with the aid of a handrail, and it soon becomes clear that this is going to be hard work. Even at 9am, the sun and humidity are extreme. Still, the views across the plain of temples all the way to the river are lovely. Apart from a large, hulking museum and an ugly modern viewing tower some distance away, the scene is bucolic.

Back at the bottom, Swe takes me into a crumbling structure that’s part of the same complex. It’s dark inside, and I’ve only just looked up after crossing the threshold when I’m confronted by a massive face. It’s a huge reclining Buddha, dusty and lit only by small shafts of natural light and Swe’s torch. He explains that the temples reflect the still widespread belief that building monuments to religion earns the builder “merit” for the next life. The richest built the grandest, tallest and most massive structures, but the thousands of smaller temples and pagodas are testament to the efforts of people with more modest means.

After visiting several temples – the interiors of the Ananda Temple are notable for their ancient frescoes and the towering Sulamani appears almost gothic in – its spiky pediments seemingly piercing the heavens. I’m exhausted from the heat and irritated to see that the concept of responsible tourism, again, seems unheard of to large numbers of western tourists, who ignore the signs asking them to cover knees and shoulders, and refrain from kissing and cuddling in public.

After a cooling coconut bought for 1,000 kyats (Dh3.5) from a nearby stall, Swe leads me back out of Old Bagan and into the fields to the south-east, where a delicious picnic lunch is laid out under a shady tree. There’s no one else around, and after devouring the contents of a seven-tier tiffin box, I lie back on the rug provided.

Swe also seems tired. “I’m ready for the next life,” he sighs, adding that while Buddhism teaches people to abide by the five principles of no killing, stealing, lying, sex or alcohol, “Buddha attained enlightenment by following the middle path. He was not extreme, so all we have to do is make the right effort – right speech, right thinking and doing.”

It’s easier the next day when Swe takes me on a jeep trip further into the interior. There are more acacia, neem, tamarind, palm, mango and old, beautiful rainbow trees, and workers ploughing the fields seem happy to see us. Swe takes me to taste palm sugar heated and shaped into melt-in-the-mouth morsels, and into industrious villages, where most things are still made by hand and few people have electricity. Even across the whole country, 45 million people – 70 per cent of the population – still rely on firewood.

The next day I fly to Heho – the gateway to Inle Lake and Kalaw, a trekking centre in the mountains. Most of the landscape is disappointingly cultivated, and my guide here, 31-year-old Min, tells me that in the past 15 years of western sanctions, Myanmar lost 40 per cent of its forest cover because of legal, and illegal, logging. Most of the country’s largest teak trees were sold to China for cash, he says. Combined with Myanmar’s constant hunger for firewood, it’s surprising there are any trees left.

Driving into the mountains north-west of Kalaw to the Green Hill Valley Elephant Camp, an apparently reputable organisation caring for elephants retired from the timber trade, I see some of what’s left of the country’s secondary rainforest. Unfortunately, there’s no time for trekking, but this would be a worthwhile spot for a later adventure – assuming these gorgeously forested hills can be afforded protection for the future.

I’m also told that due to habitat loss and poaching, only a maximum of 3,000 Myanmar elephants still roam wild, and these are mostly further south.

I’m more cheered by Inle Lake, which, because if its long-standing position as a tourist draw in Myanmar, I’d imagined would be more built-up. Because of its size and marshy geography, the edges of the lake are, apart from a few large resorts on stilts, pleasing to the eye.

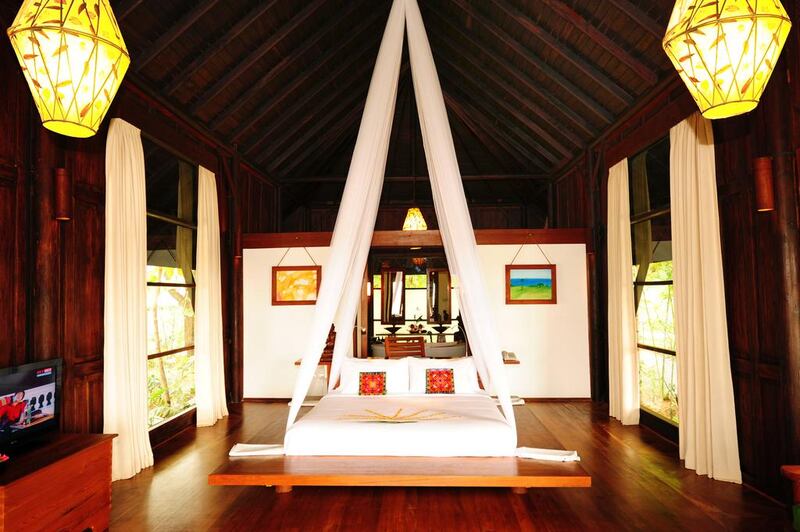

My hotel, the Villa Inle Resort & Spa, on the north-eastern shore, is a blissful retreat. I have one of 27 high-quality wooden bungalows on the lakeshore, and it has polished wood floors, soaring ceilings, a roll-top bath and heavenly bed shrouded by muslin netting. From my terrace I can't see anything but the lake and mountains; crickets and frogs screech and croak as the rain comes down.

The next morning, after a breakfast of mango, rice pancakes and mohinga, I’m collected from the hotel’s private jetty in a traditional 10 metre-long wooden boat, equipped with a snappy Chinese two-stroke engine. We set off across the lake through the “floating gardens”, where vegetables – mostly tomatoes – grow on rows of watery clumps of earth and weed, to the open lake. Declared a Unesco Biosphere Reserve, the 116-square-kilometre expanse, which has a maximum depth of about four metres, faces various threats, including pollution from homes, factories, agriculture, boats and hotels; this is only mitigated by the fact that the lake is fed a constant supply of fresh water from the mountains in the north, which drains out at the southern end.

I'm still pleasantly surprised at how wild and fresh it feels, and it's exhilarating to be one of the few boats within sight. We accelerate to about 25kph in a light breeze, and the clouds and mountains make for dramatic pictures. We're heading south to a rustic market at Taung Tho; next we visit the Inthar Heritage House, which has a good restaurant and what is said to be Myanmar's only breeding collection of Burmese cats. We see a lotus-weaving factory, where this incredible and laborious craft can be seen in all its stages, from the pulling of threads from inside lotus plant stalks to the shop selling the scarves, which are three times the cost of silk – prices for a scarf start at $75 (Dh275.4), but I'm told that this will use a staggering 10,000 plants. We seek a teak boatyard and a silversmith before a delicious lunch at Grandma's Kitchen, in the wooden home of a fairly wealthy family who had owned a cigar factory. There's spring onion tempura with tamarind salsa, salads, Shan noodle soup and green tea, which is more like a woody oolong.

On my last day, Min and I head into the mountains north-east of the main township of Nyaungshwe for an 18km hike to a village inhabited by the Pa’O people (Min is of the Inthar tribe, which is the main group from the Inle Lake area). Just getting to the starting point involves a 40-minute boat ride followed by 15 minutes by horse and cart.

It’s a good hiking route, and we only see two other tourists all day. At the highest point, we have another delicious lunch in a bamboo home, amid an agrarian idyll of cornfields, bamboo and thick woodland.

Back down near the bottom I can hear the sad sound of rocks being mechanically excavated, and there’s a new road and power lines to a school. Then, a bit further along, there’s a medieval scene of wooden farm buildings, an ox tilling a field and the perfumed smell of wood smoke.

At the lakeside I’m transferred back to my hotel by boat. Hot and scratched from the hike, I throw myself into the lake for a swim. It’s refreshing, clean and peaty, and I’m glad I did; who knows how long it will remain this way?

Read this and more travel stories in Ultratravel magazine, out with The National on Thursday, September 29.

rbehan@thenational.ae