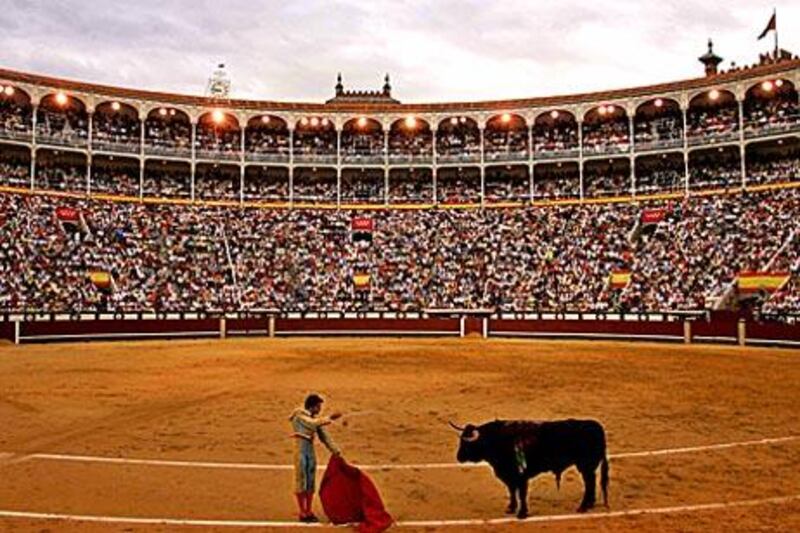

Simple but enigmatic, raw yet sophisticated, the Spanish capital is a city of paradoxes. The author Jason Webster sets out to unravel its mystery. There is a hush as the crowd falls silent and all eyes are concentrated on the lethal dance between man and beast on the sand below. The matador, clad in a dark blue "suit of lights", with gold embroidery flashing in the intense sunlight, flicks his red cape in front of him defiantly, urging the bleeding bull to charge at him, knowing that only by drawing the animal in, by using its own violent instinct, can he take it off its guard and so kill it before it kills him. In the still, roasting air we can hear the bull's gasping breaths as it searches for the strength to continue the battle. The matador raises his sword above his head, ready to thrust; the bull lowers its horns, pawing angrily at the sand. Then all at once, it breaks into a run... Having some grasp of bullfighting - whether it fascinates or disgusts you - is key to understanding Spain, and I have come see a fight in Madrid as part of the research for a novel I am writing. They say the city's bullring - Las Ventas - is the most important in the world, that for a matador to triumph here is the greatest honour in his career. Madrileños, as the locals are called, are the most knowledgeable aficionados of the spectacle, and pride themselves on being the most demanding. But as with so much else in Spain, I am finding that the more I discover, the more mysterious and complex everything becomes. Even after living here for more than 15 years, few things are as they initially appear. The city of Madrid itself encapsulates this Spanish paradox. At first sight it may not be a particularly striking place. It lacks the elegance of Paris, the majesty of Rome, or the buzz of London. Like Washington or Bonn in the former West Germany, it is a made-up capital, a city that had importance thrust upon it rather than finding it itself. Architecturally there are few highlights, the climate is famously severe ("nine months of winter and three months of hell" is the Madrid saying) and the people can be brusque at times. And yet despite this there is no doubting it is one of the great European cities. It's just not easy to put your finger on exactly why.

Madrid started life as Majrita, a fortress built during the time of the Emir Muhammad I in the second half of the ninth century to defend the borderlands with the Christians to the north. Later a town developed around it where the Andalusi astronomer and mathematician Maslama "el-Majriti" - the Madrileño - was born. Conquered by the Castilians in the 1080s, it remained a small town until in 1561 Philip II decided to turn it into his capital city. Until then the Spanish court had moved around the country like a travelling circus. Philip wanted somewhere right in the centre of the Iberian Peninsula so he could stay put. Madrid fitted the bill, and what's more, the weather suited his gout. And so Madrid as we know it was properly born. But even then it took a while for it to grow into its new role as imperial capital. Next to the new palaces and government buildings ordinary people carried on living as humbly as before, and foreign visitors back then talked of a dirty, unhealthy place with little to recommend it. And yet at the same time it was home to such greats as Cervantes and Velázquez and Spain's 17th-century cultural flourishing, what became known as the Golden Age. The paradox was already finding its feet. There's no better place to immerse yourself in this Madrid mystery than the Prado Museum, one of the finest art collections in the world. In fact, so important is the museum that it is almost impossible to imagine Madrid without it; each one gives identity and context to the other. Only very briefly, during the Spanish Civil War, was the city separated from its paintings, when they were transferred abroad for safe keeping. But once the fighting finished, the art works were taken back and restored to their original home. An inventory was carried out; of the thousands of items, miraculously not a single piece had gone missing. Like Spain the country, or Madrid its capital, the Prado is not an unchallenging museum, however. Yes, there are pretty pictures here, easy on the eye, aesthetically pleasing. But the big artists on display - Goya or El Greco, for example - offer disturbing, demanding, often violent images of both our interior and exterior worlds. Death, either physical or spiritual, is something of a running theme, be it in the tortured, twisted limbs of an El Greco saint, or Goya's grotesque monsters. Even Velázquez, with his courtly style, can be almost shockingly complex and subtle. His masterpiece, Las Meninas, takes us into daily life in the royal court, but is also a curious play on the observer and the observed, to the extent that who is actually being depicted (the little princess? Her royal parents who commissioned the painting? Velázquez the painter in the background? Perhaps even the viewers themselves?) becomes unclear. Personally some of my favourites are the portraits by Goya. For many he is the first modern painter in Western art, and staring at these deeply unflattering, psychologically complex yet somehow affectionate depictions of the early 19th-century Madrid aristocracy, you begin to understand why.

Let's imagine you've spent a good few hours in the Prado by now, and, saturated in these images, you step back out into the streets to clear your head. But stretching your legs as you stroll towards the Puerta del Sol - the centre of the city and the geographical heart of the whole country - the Madrid paradox strikes you again. Yes, there are finer cities in the world, but something about the place is getting under your skin. Like those Goya paintings, there is a different kind of beauty here. Not the kind that strikes you at first glance, but a subtler, more complicated, dirtier beauty that appeals not to your heart, but which gets under your nails and seeps into your blood. The sun is dipping low and the air is gradually cooling. It's time to sample what the city is best known for after the Prado - the tapas and nightlife. The heady days of the 1980s, when the city rocked to the post-Franco party known as La Movida, have long gone, but a night out in Madrid is about as essential as a visit to the Eiffel Tower is for Paris or the pyramids for Cairo. And the best area to start for this most Madrileño of rituals is La Latina district, to the south of the Plaza Mayor. Essentially a kind of snacking on canapés, going for tapas is a great way to spend an evening, eating enough to keep you going, but never so much that you get too full. And when the general plan is to stay up all night this can turn into the perfect meal; some cured cod in one bar, spicy potatoes in another, then a slice of tortilla in a third. It's also a great way to meet local people. Some of the directness you may have encountered earlier in the day gives way to a more relaxed, open disposition, and if you're in luck, you can fall in with a group of revellers whose group momentum keeps you going through the night, perhaps stopping off at a few flamenco bars along the way. Not the touristy places, but the more authentic tablaos where you're more likely to experience duende, the mysterious and indefinable power that lies at the heart of this most passionate of art forms. The Corral de la Morería and Cardamomo are good places to try. The hours tick by, and by now, if you have the stamina, the sun is creeping its way again towards the horizon, and it's time to try out another Madrid tradition: churros con chocolate. What better way to round off the night than with some hot chocolate so thick you can stand your spoon in it, complete with sweet, gungy pastries? It will certainly line your stomach until you get up in time for a late lunch. Alternatively, if you're able to keep going, the Rastro flea market on Sunday mornings is another chance to find some Madrid magic. A seeming endless labyrinth of streets packed with stalls selling anything you could possibly imagine - and more - stretches down the Calle de la Ribera de Curtidores. A host of antique shops line the sides, and most stay open for Sunday mornings. Even if you're not interested in buying anything, it's a perfect spot for people-watching, and there are still some old-school characters out there. A lot of what's on offer may be rubbish, but search well - there are some real gems to be found. Just be careful with your handbag or wallet in the crowds, though. If Madrid hasn't got to you by now, the chances are it never will. There is something raw, life-loving, earthy, swaggering and generous about the city. It took me a while to see this, and to become enamoured with the place. But as with so much about Spain itself - the flamenco, the art, bullfighting, the people - taking time to learn and understand can bring huge dividends. First impressions can deceive; the paradox pushes many people away. Yet it is also the key to unlocking the mysteries that lie hidden from view. Accept Madrid for what it is and what it gives you - this is the secret to being allowed inside.

Jason Webster's novel, Or the Bull Kills You, will be published by Chatto & Windus next year. Return flights from Abu Dhabi to Madrid start from US$1,056 (Dh3,885) on Etihad Airways (www.etihadairways.com). Hotel de las Letras is ideally located at the heart of the city. There's a restaurant on the ground floor, open-air rooftop bar open from May to October, a spa, a library, and rooms are individually styled with literary quotes from famous writers on the walls. A standard double room costs between $152 (Dh557) and $336 (Dh1,233).