"Can you fly?" My guide, Faris Janini, half-smiled at me from across the water. As we were halfway down the wadi, there was no other way forward. I took a few steps back, started running, and jumped, landing just on the other side. "Good," he said. "Now let's go." This was just one of several tests I had to pass on the hike from Hammamat Ma'in to the Dead Sea through one of Jordan's most spectacular but little-known wadis. Over the course of the three-and-a-half-hour adventure, I would wade through rapids, swing around boulders on ropes and descend waterfalls by ladder.

Yet it was only meant to be a short stroll. The trip began with an argument with the activities coordinators at the new Six Senses resort, perched at the end of Hammamat Ma'in, staring into the wilderness. I asked for a map. "We can't give you a map," said the coordinator, who specialised in charging people for trips. "Sit down and I'll show you some photographs of the place. There's also a video on YouTube." I explained that I didn't want to watch a video, or look at any photographs - I just wanted to walk. "You can't go walking by yourself, it's too dangerous." They could, however, provide me with a guide at the reduced price of 52 Jordanian dinars (Dh270). "It's hard, and you're going to get wet," the coordinator warned. I said that sounded brilliant.

We set off down the valley at 7.30am the next morning at breakneck speed, with Ma'in's popular thermal waterfalls behind us. From the start, there was no path. "Usually, this walk takes longer, but you have a flight to catch," Faris reminded me. We crossed a small, hot stream - most of the water coming from the volcanic mountains in this area comes from hot springs deep underground - so the water, whenever we touched it, varied between 45 and a steamy 65 degrees.

Turning a corner, I looked back and the hotel was gone. Before us the riverbed widened and the sides of the valley appeared to steepen. The water coursed between large boulders and the scenery was wild, with reeds and small bushes lining the river. We criss-crossed the stream dozens of times in the first hour, trying to find the easiest route downhill. Sometimes Faris would lead me across the scree and woodland at the side of the water; at other times we would have to scale large boulders or simply walk through the river.

Faris, a 42-year-old from nearby Madaba, who had spent most of his life as a tour guide in Italy, walked across boulders as if he was walking on air, barely breaking his stride to negotiate the different levels. I was more careful - I didn't fancy waiting to be airlifted to the hospital from here - but still found myself fooled by the thick volcanic mud below the surface of the almost-clear water. Sometimes it had a light brown tinge which made it look just like rock - but when you stepped on it, a thick black mess would envelop you up to the knee. By 8.30am my head was pounding. Far from taming the experience, having a guide pushed me to my limits. Luckily, the valley walls shaded us from the worst of the 42 °C heat and the sun. My hands had become red from pulling myself up onto rocks and sliding down the other side - fortuitously, Faris discovered a pair of abandoned climbing gloves on a ledge which made all the difference.

I was surprised to see small, melon-like fruits growing on vines along the valley floor. Faris explained they were inedible but were hollowed-out and used by local Bedouin to treat knee conditions. We stopped at a bend in the river and sat down to rest in the breeze; Faris presented me with bottles of cold water, orange juice and - thoughtfully - fruit skewers. Looking around me, the scene was as beautiful and wild as I have seen in any of America's national parks - which set a high bar when it comes to the dazzling beauty and wilderness of rocks, mountains and water.

The most gorgeous part of the wadi was about halfway along it. The greenery was luxuriant - thick reed beds, mature trees and palm trees sprouting out of the side of the cliffs like hanging gardens, all watered by the light green water running through the rocks. "Of course, you can't do this in the winter," Faris ventured. "When it rains, the river rises to up there," he said pointing to a line on the rocks 20m above. "Two years ago in February, there was a Russian couple who were under the waterfall near the hotel. They had been drinking and had been warned not to go near the water. But they did. They were swept away and we found the body of the husband near here. Two days later we found the wife in the Dead Sea."

It's easy, travelling around Jordan, to see it as a completely dry country. Its water shortages are well-known: much of the eastern part of the country used to be wetland but this was almost completely drained between 1960 and 1990; in recent years, the winter rains have been steadily diminishing - some think, because of global warming. And from above, from the mountain plateau at the edge of the Jordan Valley - part of the Great Rift Valley extending all the way south to East Africa - even Wadi Zarqa looks like just a dry, bare crack in the ground. It's only when you get down into the wadis that you see where most of the water in the Dead Sea - itself dropping by some three metres a year - comes from. It comes steadily from the mountain rock, the same unfaltering warm current that created these wadis and all this beauty. "If we don't have this water, we get a volcano," said Faris, philosophically.

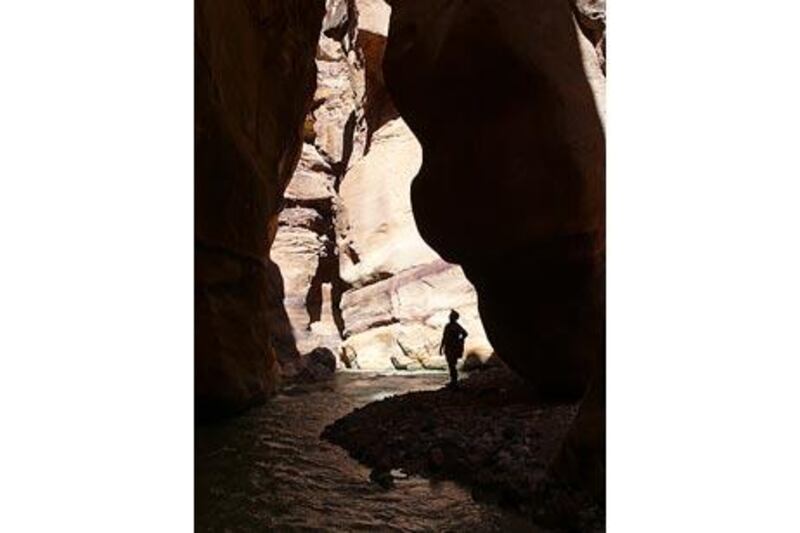

Past the centre of the wadi, the river seemed to flatten out. We passed under dramatic overhangs in the rock, their edges smoothened, striated or pockmarked by millions of years of erosion. In some places, layers of coloured sediment - white, yellow, brown and ochre - appeared almost to have been painted on. We walked along the side of a small canyon - the water at various levels had gouged its way through like a scoop through ice cream - and gripped the side of certain sections with both hands to avoid plunging earthward. In my favourite section, layers of rock on one side of the narrow stream faced the other, which was covered in palm trees. The stream then widened to a gorge and we arrived at the top of a waterfall. Luckily, some determined hikers had installed a rope-ladder. The sky then opened out as the stream seemed to diminish and we could see the mountains above and behind. Yet still the Dead Sea was out of sight. The next thing we knew, we were enclosed again - this time by a solid vertical mass of sandstone. Wading through it, it felt like being in the Siq in Petra, except that here there was water. Its colour here seemed to be a light turquoise, with all traces of mud and sediment gone. It was a watery paradise which I could have spent all day looking at, but we had to press on.

The cool of the canyon and a welcome stretch of horizontal ground helped us on our way. The sides of the canyon became taller and the centre narrower, so soon it felt like we were exploring a cave system. The shallow, clear water showed we were almost there - as, unfortunately, did the first signs of litter. What had been a pristine environment for the past three hours suddenly yielded empty drinks cans, yoghurt pots, old nappies, fire remnants and pieces of carpet - horrible signs that we were close to the end. How people can come to enjoy the stunning beauty of a place and then wilfully pollute it like this is always upsetting, but luckily, the walk is so challenging that few can make it more than several hundred yards from the road.

Finally we arrive at the end. The Dead Sea is there in front of us, and so is the wide river mouth, but the water is gone. Where the water should be rushing into the sea, there is a deathly, still silence. To my right I see the reason - all the water from this wadi, every last drop of it - goes no more to the Dead Sea but is siphoned off to Amman in a concrete aqueduct. It's not suitable for drinking, Faris tells me, but it's used by factories. One can hardly blame a country so in need of water, but looking at the Dead Sea stretched out ahead of me, it's no wonder that it's shrinking. rbehan@thenational.ae

The 215 sq km Wadi Mujib Nature Reserve was established by the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature as a breeding centre for the Nubian ibex but is home to more than 400 species of plants, 250 animals and 186 species of birds. There are numerous trails through the Wadi Mujib gorge, including the Siq Trail, Malaqi Trail and Mujib Canyon Trail. The wadi's visitor centre lies next to the Dead Sea Highway or book through the RSCN/Wild Jordan centre in Amman (www.rscn.org.jo; 00 962 461 6523); accommodation can also be booked here.

The Dana Nature Reserve is the largest in Jordan and was taken over by the RSCN in 1993 as an ecotourism venture. There are several wadi hikes here, including the 14km Wadi Dana to Feinan walk which can be self-guided, and the 16km Palm Trees Wadi Tour from Al Barra through Wadi Ghuweir to Feinan Lodge. There are several impressive places to stay here, including the Dana Guest House and Feinan Lodge, as well as a campsite. Book through Wild Jordan (left) or contact the Dana Nature Reserve visitor centre on 00 962 227 0497.

Wadi Yabis is a 12km day hike from Hallaweh village north of Ajlun near Jerash: you'll see canyons, waterfalls, wildflowers and ancient olive trees. The walk finishes at Wadi Rayyan dam.

Wadi Hasa is the second-longest canyon in Jordan after Wadi Mujib; walking its 24km brings you to pools, waterfalls and hanging gardens. The trail begins near the police checkpoint 45km south of Karak on the King's Highway; it ends near the village of Saf.