Down a side street off a narrow lane in the labyrinth of Fes, a small shop is being mobbed by customers. All of them are women, all shrouded in veils and voluminous jellaba robes. On display around the entrance is an assortment of curiosities. There are dried alligator heads, aromatic roots and barks, live chameleons, crystals, rock sulphur, and giant tortoise shells. In the middle of the crowd is a young woman called Fatima, who's looking for love. She hands over about $4 (Dh14), and is rewarded with a sprig of a sweet-smelling herb and a phial of bright pink liquid. The owner of the shop, Abdul Lateef, runs through the directions: "When you find the man you like, make a tea with the ingredients, and get him to drink it, but only when the moon is a quarter full. He must consume it in one gulp ... do you understand?" Fatima nods intently, turns, and hurries away.

Abdul-Lateef and his magic-medicinal stall are a fragment of a healing system that stretches back through centuries, to a time when Fes was itself at the cutting edge of science, linked by the pilgrimage routes to Cairo, Damascus and Samarkand. The magic market in the old city may have competition these days from highbrow pharmacies in the new town, but its shops and stalls continue to do brisk trade.

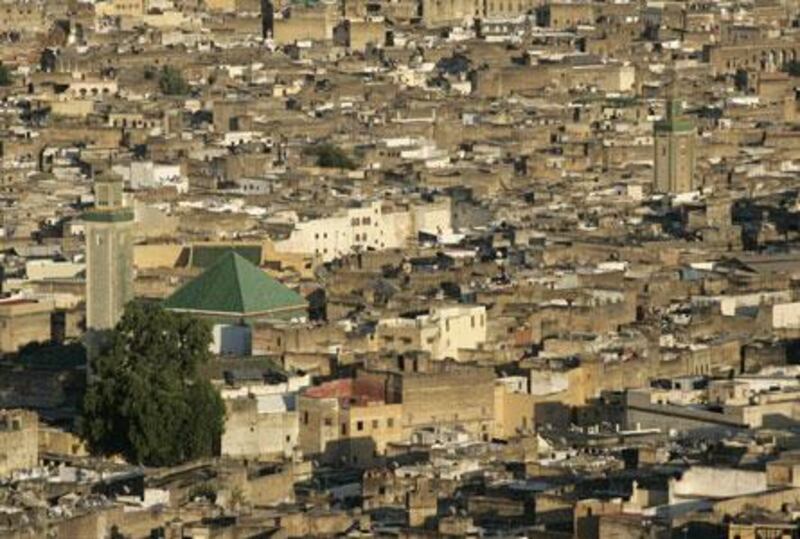

The reason is simple. Fes is a city which moves to an ancient rhythm, because its roots sink deep down deep to the bedrock of medieval Morocco. It seems as though a shroud has covered the city for centuries, the corner now lifted a little so we can peek in. Once the capital of Morocco, Fes is one of those rare destinations that's bigger than mass tourism, a city that's so self-assured, so grounded in its own identity, that it hardly seems to care whether the tourists come or not. Moroccans will tell you that Fes is the dark heart of their kingdom, that it has a kind of sacred soul. And in many ways it's true.

Amble through the endless labyrinth of streets that make up the medina, and you can't help but be touched by a way of life that has changed surprisingly little in centuries. There are few vehicles, but instead pack mules laden with bales of newly tanned leather, crates of oranges, and builders' bricks. Fes is the only medieval Arab city that's still almost totally intact. To wander through the honeycomb of interconnecting passages is to be transported back in time, through a keyhole into One Thousand and One Nights.

Thankfully, during the occupation, the French governor understood how important and fragile the ancient cities of Morocco were. For this reason he established new towns alongside the medinas, allowing centuries-old traditions and architecture to remain intact. The result is a veritable time capsule of Arab culture. The first thing to do once you arrive in the medina is to dive in and get lost. There's no feeling quite like it. When I'm there, I never hire a guide. In my experience, they overwhelm you with facts and figures, when you should be going slow, taking in the detail. If you get lost, find the nearest 10-year-old kid and give him a few dirhams for taking you to a known landmark, like the magnificent Bab Boujloud. And remember, when in Fes, if you're going up hill, you'll eventually break out of one of the city gates.

Turn left or right off the main drag, Talaa Kebir, and turn again, and again, down telescoping streets. It's near impossible not to become disorientated. Peer into any of the open doorways and you'll spy dozens of small workshops in which artisans toil away, making brass appliqué lamps, pottery, mosaic fountains, musical instruments, or exquisite woven cloth. I can think of no city of earth quite so mesmerising in the sheer quality or range of crafts it turns out.

Though a low doorway near Bab R'sif, Hassan, the son of Tahar, sits crouched over a sheet of burnished brass. Nudged into his eye there's a jeweller's loupe, and in his hands, a mallet and a steel chisel. With a care he learned in infancy, the artisan etches an elaborate octagonal pattern over the surface of the brass, a motif taught to him by his father, and passed on through 11 generations of the same family.

From time to time he pauses from the tap, tap, tapping, sips a glass of sweet mint tea, and rubs his eyes with his thumbs. "Most of the work we do here in Fes is sold in the souqs of Marrakech," he says dolefully. "Tourists there think they are buying local wares down there, but they're not." Hassan takes another sip of his tea and glances at his watch. Excusing himself, he removes a worn prayer rug from the shelf behind him, and heads out to the mosque.

Another craft with a long history in Fes is leatherwork. Tapered yellow slippers, known as babouche, made from supple sheepskins, are an icon of Morocco. The leather is tanned at the ancient leather tanneries in the medina, whose dying pits have endured since the days of Harun al Rachid. No visit to the city would be complete without taking in the jaw-dropping sight - or the pungent smell - of the skins steeping in pools of dye.

Yet another craft that's all but disappeared elsewhere is the art of mosaic-making, known as zelij. Whereas European mosaics tend to be square, in Morocco, they are found in hundreds of hand-cut shapes, chipped out from glazed tiles. The cutting, and the assembly of the pieces, is nothing short of miraculous. It continues at the kilns just outside the city, themselves fired by olive stones as they have been since the Romans introduced the craft to North Africa.

Despite the giddying array of crafts manufactured by hand in the medina, Fes is about much more than the tourist objects for sale. Even the quickest visit gives you a sense of the city's extraordinary cultural and intellectual heritage, and helps to remind all who come of the towering achievements of the Islamic faith. The centrepiece of this is surely the Al Karaouine university and its mosque, which was founded in 859 AD, regarded as the oldest continuously used centre of learning in the world (it's even in the Guinness Book of Records). Al Karaouine is just one of dozens of medieval medrasas, religious schools, found in Fes. A number of these are now being restored, some of them with grants from Unesco.

One of the most refined of all is the Bou Inania Medrasa. It boasts fabulous mosaics, geometric cupolas crafted from cedarwood, and tiles carved with couplets from the Quran. No visit to Fes would be complete without spending a few minutes there, soaking up the atmosphere. Across the street from it stands the remains of the city's once-grand medieval water clock, now ruined. It was on this street that the 12th-century Andalucian philosopher Maimonides once lived. Tucked away behind it, to the left of a fishmonger's stall, is a new jewel, Cafe Clock.

The cafe came from the imagination of an indefatigable Yorkshireman, Mike Richardson, for whom Fes was love at first sight. The outstanding food hints at Mike's background in catering - he was a maitre d' at The Wolseley and, before that, London's celebrated restaurant, the Ivy. But Morocco is a long way from the West End. One of the first hurdles to overcome was the search for fresh ingredients, a quest that eventually led to a fusion of cuisine.

Poised on the menu between Caesar salad and cheesecake are the words "camel burger". Mike pushes back his mop of ginger hair and exclaims, "I searched for years for the perfect meat for burgers, and I found it here in Fes. Camel meat's got the ideal consistency and succulence, and it sits so nicely on the bun." The burgers are by far the Clock's best-seller, so much so that Mike spends much of his time trawling the bazaars in search of fresh camel meat and the other ingredients needed for his secret recipe. Yet for Mike Richardson, his cafe is about much more than slaking hunger pains. He feels a responsibility to highlight a little of the heritage for which Fes is so renowned. Each evening, after tucking into their camel burgers, visitors are invited to learn from Moroccan experts. There are regular lessons in the art of calligraphy, music, dance, and talks on facets of local culture, such as Ramadan.

In the last handful of years, quite a number of foreigners have dropped everything and moved to Fes. Most of them, like Mike, have been attracted by the gravity of the place, the kind of serenity that's absent in other more carefree tourist hot spots. You get the feeling that they can't quite believe their luck at having the chance to be living in such a magical destination. The growth in visitors buying second homes has led to a proliferation of local people wheeling and dealing in property. It's hard to walk down the main arteries of the medina without being offered a little house, or a palace for sale. Few people in Morocco go through estate agents. Instead, they use a network of so-called semsars, whose business it is to know which homes would be for sale at the right price. They stand on street corners, waiting for a visitor with that glazed looked of wonder ... a look that every visitor seems to have.

One drawback is that it's all too easy for tourists to feel they're somehow on the outside. But visiting houses for sale is an excellent way to catch a glimpse of real Fes, life behind the doorways, and to get access to a world that's often closed. Simply describe to a semsar what you're after, and a minute or two later, you'll be trawling through homes built centuries ago, in which several families may co-inhabit. The wonderful thing about viewing such properties is the sheer zaniness of it all. I was recently touring some properties down in R'sif, where the seed of Fes fell more than a thousand years ago.

First I was offered a home in the basement of which were the tombs of six generations of previous owners. The house had grand views over the medina, but I couldn't get the thought of all those skeletons out of my mind. The next property was a palace, replete with a walled orange grove, fabulous zelij fountains, intricately carved cedarwood ceilings and dozens of rooms. Inside it lived an old man who made leather sandals for a living. He told me that he rarely went outside and that he had been born in a small bedroom on the first floor. He said he had no friends, except for the doves that lived in the rafters of the drawing-room.

The third house I visited was far smaller than the rest, with four sets of cedar doors off the tiled courtyard. The building was more than 500 years old, and had an ambience of age and consequence that almost defies description. When I lamented the fact that I didn't have the money to buy it the owner, an ancient character called Hamid, winked. "That is not a problem," he said darkly. "How is that so?" I asked. Hamid sent withered fingers through his white beard.

"Because under the floor there is a huge treasure. Buy the house and you can dig it up." I looked at Hamid, then at the exquisite tiled floor, worn where generations of feet had trooped over it. "There is a question that I must ask," I said. "If there is a vast treasure under the floor, why don't you dig it up yourself?" Hamid leant down and kissed the head of his little grandson. He smiled dreamily. "Do you have any idea what problems a treasure like that would give a man like me?" he said.