Under high limestone cliffs, the riverbank is decorated with flowers - saffron-coloured chicory, lemony China asters and bird of paradise. Clouds of floral scent hover in the sultry air of an imminent summer monsoon. It's the first day of Asanha Bucha, when giant yellow candles infused with kamene herbs are lit in ceremonies to mark Buddhists' annual monastic retreat. "This is the beginning of our rainy season," says Eddy Ladplee, our guide, as we hurtle through the Kwai River canyon in a swallowtail boat, powered by a demonic-looking outboard motor with a flange like a horn. "Many living creatures are moving about. Buddha said it's better to stay in the temple, not hurt them." On cue, a fat iguana swims in front of our bow. The Kwai River flows warm as cocoa, frothy with nutrients washed down from the jungle hills. We are 250km west of Bangkok, in a mountain fastness near the town of Kanchanaburi.

The landscape is redolent with history, myth, and botanical delights: it's difficult to stop smiling. Yes, 6,000 Allied soldiers died here, building the infamous Burma Railway as prisoners of the Japanese Imperial Army. But today the canyon is blitzed by neon-yellow beecatchers. Chocolate butterflies compete with flocks of citrus butterflies for the easy nectar of high summer. Local people say the brilliant beings are souls of the dead, reborn to idleness and joy. Our destination is River Kwai Jungle Rafts, a collection of 50 bamboo huts perched on pontoons and anchored to the south side of the river directly below a Mon village. "I bought the land across the river, too," says the director, Suparerk Soorangura, 52. "So it would stay undeveloped. It is important to keep a small footprint, everything in balance."

The project was originally conceived by a Frenchman, Jacques Bes, an engineer who fell in love with indigenous river rafts in the 1970s, when the Mon tribal people built him one as a temporary lodging. Suparerk took it over in 1985 after consulting with tribal elders. "I asked them if they wanted to participate in tourism. It was their choice. Most said yes, so today over 100 of the 120 people in the village work in our four hotels. We deliberately keep the rooms to only 50." Suparerk began designing the canvas tents for his first project, Hintok River Camp, on the site of a former Japanese officers' camp a few kilometres downstream. "I wanted people to be able to stand in the tents, and I put bathrooms at the back. No need to go outside at night," he laughs. "See that faded bamboo hut? When it gets old it will be burnt to ashes and a new one installed. Not like concrete." No swimming pool either, only the river. Guests are floating freely down the slow current of the Kwai in life jackets. A forest path leads directly into the Mon village by a heavily forested hill. The Buddhist holiday is in full swing - which means nothing is happening. Well, that's not strictly true. Some women are carrying offerings of fruit and tea in silver vessels on their heads into the temple. Two teenage boys light incense and kneel and pray at an outdoor altar. The blue demigod has a bloodied sword and a pointy coiffure like Elvis. High above the village, a boy negotiates the steep path to reach a grotto in the cliff face. He squats at the mouth of the cave, peering inside, as if something big is happening in the dark. I take up a position by a vast singha, the great lion-dog protector, an anatomically-complete male, and promptly go into a meditative state. One minute I am another tourist, thinking about lunch - green mango salad and grilled fish? And the next I have flown from a Sunday afternoon in the jungle with incense and butterflies for company to a bliss somewhere between life and memory.

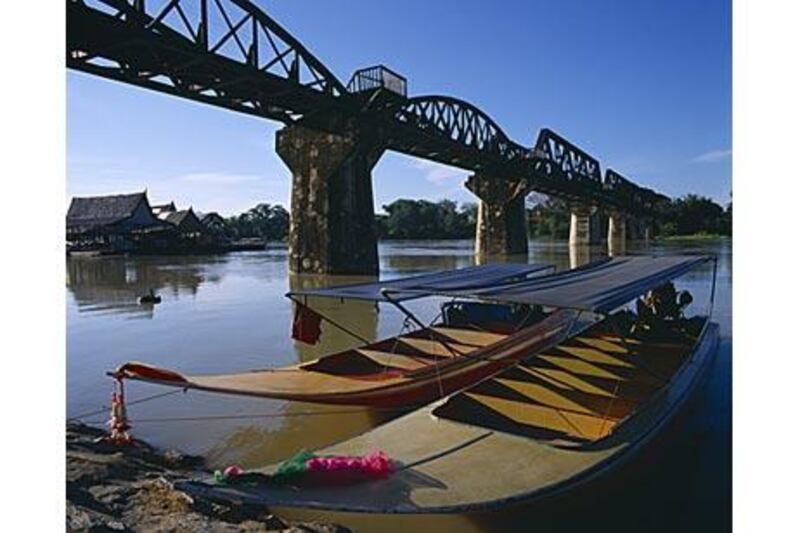

Morning comes with squawking birds. Eddy our driver arrives to escort us to the place I have been dreading all week - Wat Pa Luangta Bua Yannasampanno, the Tiger Refuge Monastery. Are we ready to appreciate the fearful symmetry of tigers? Live ones, running freely? Rubbing their big furry heads against our legs? Eddy gets us to the River Kwai Bridge in Kanchanaburi town by noon. Scores of foreign tourists are taking pictures of each other. Their obvious glee at seeing the train made famous by the celebrated Hollywood film is heartening - if at odds with the region's tragic history. "Not many Japanese come here," Eddy says. "Perhaps it makes them uncomfortable. Last year a 90-year-old British army veteran came to visit the war cemetery. It was moving to meet him." The train still runs, an old-fashioned steam locomotive loaded with families. It chugs past a modern sculpture spelling out "no war" in red-and-black letters and crosses the river via a timber trestle bridge - like the one Alec Guinness blew up and the real British colonel didn't - and disappears into the shimmering jungle. The private Jeath War Museum on the square features plaster statues of Hitler, Stalin, and Churchill. They compete for martial glory with warrior demigods from the Buddhist pantheon. The artists saw fit to use the same bright blue paint for all their terrible faces. "Would you like to eat something, or wait for lunch with the tigers?" Eddy offers, eyeing the snack carts selling grilled chicken kebabs. "Or shop for local gems?" "Are we allowed to eat meat before petting tigers?" I ask him, trying to recall the protocol from my brief conversation with Wat Pa staff. One wants to do everything exactly right when it comes to live tigers.

A few kilometres south of Kanchanaburi, we pass a sign at the entrance to the 100-hectare Forest Tiger Monastery. It is explicit: "hot colour is dangerous". If you wear red, pink or orange you will not be able to enter the canyon or touch a tiger. Visitors are stuffing their vivid scarves and dangerous sweaters into handbags. One husband is not quick enough to get the point, according to his wife's shrill remonstrance; she snatches the red golf hat from his hand and stuffs into her purse with a sigh of exasperation. We join a long line of tiger-seekers at the mouth of a steep, dry canyon. It is preternaturally silent. No growls, no rending of bones. Just random shrieks of unseen peacocks, inane screeching that marks a line of predatory shadows. Suddenly we are inside the canyon's high sheer walls, moving forward. We turn a corner and a Buddhist monk appears out of a dust cloud with a big animal. It has a broad face like a kabuki mask. We follow, but at a distance. Now there are tigers everywhere. Only a thin wire separates us from a chalky pit where the fierce creatures loll in the sun on long chains. The formal dress code does not apply to Buddhist monks. One monk in the saffron robe of the Theravada order cavorts with a giant feline. Another big cat is getting his backbone scratched by a solicitous attendant. The young students wear the yellow T-shirts of the Wat Pa Foundation. They act causally, but are still - focusing intently on the risky space around the muscular animals at all times. Altogether there are maybe a dozen tigers in the exercise yard - rescued from poachers, abandoned litters, lost habitat or serious illness. The foundation was started by a Thai veterinarian named Somchai, who arrives to tell us that of the seven tiger subspecies native to South East Asia, only five survive today. There is a Bengal, a Siberian and a Malay among their rescued charges.

"I was, of course, a tiger in a previous life," says the director. "Whatever you do," says Somchai. "Do not show fear. Do not run or make sudden movements. And never turn your back on a tiger." I stop thinking and instead move by instinct. The tigers are supple, suggestive as smoke. Their whiskers twitch larger than life. Tourists kneel and stroke them reverently. Iridescent peacocks cry in the woods around us, water-buffalo stomp their hoofs. Somchai smiles, mayor of all we fear. It's a jungle city of terrible beasts, a children's classic come alive. One of the lithe tiger-boys invites me to meet his charge. The supine beast stretches from one edge of my vision to the other. He pants and purrs like a two-stroke bike in low gear. I wait to be introduced. Larry Frolick is the author of Grand Centaur Station: Unruly Living with the New Nomads of Central Asia