Less than an hour after landing at Larnaka's shiny new airport, I'm trailing in the wake of a man with a clipboard who's galloping towards the car park. My family and I have arrived in the Republic of Cyprus but we're not stopping to walk in the Troödos mountains or admire the archaeological delights of Pafos; no, we're heading north, to the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). The man dead ahead is our taxi driver who's going to take us through the UN-controlled border area, expedite the paperwork and unite us with our hire car.

The process goes smoothly: the queue of cars waiting to cross just outside North Nicosia is somewhat chaotic but there seems to be no animosity between officials wielding stamps and those waving passports and visas. Back on home ground, the taxi driver puts the magnetic "taxi" sign on the roof of his dusty car and speeds away. It's not the typical start to a family holiday but then, very little about northern Cyprus is entirely straightforward.

In spite of the enormous pair of red-and-white Turkish and TRNC flags emblazoned on the hills as you drive north-west from the international airport to the border crossing, Turkey's invasion of the north in 1974, after a decade of sectarian violence between Greek and Turkish Cypriots and a failed mainland Greek-led coup, is highly controversial. Only Turkey recognises that the state exists at all. Failed attempts by the United Nations to negotiate a federal state, the presence of some 30,000 Turkish troops and a UN peacekeeping force is testimony to the tension and bitterness that exists on both sides. But for the tourist, northern Cyprus promises that great prize: the unspoilt destination, far from the maddening crowds of the Spanish Costas, Turkey's Aegean coastline or, whisper it, southern Cyprus. We're set to experience the contested region at its best - and worst.

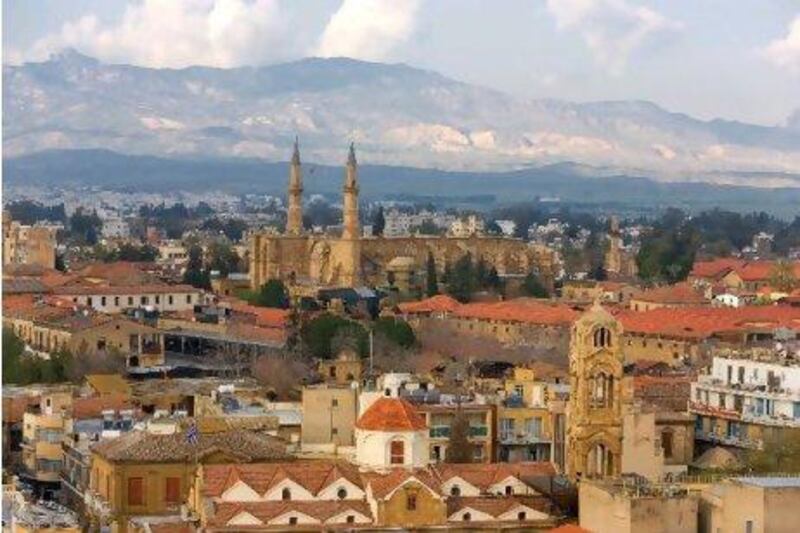

The island's divided capital, Nicosia is a telling barometer of the two republics' differing fortunes. We park just outside the city's crumbling Venetian fortifications, which were completed in 1567 after almost 400 years of Frankish and Venetian rule but too late to deter the Ottomans from laying siege just three years later. After the conquest, some 20,000 Turks settled from the mainland and the Ottomans remained in power until the British negotiated the right to administer the island in 1878, keen to gain a strategic trade and military outpost in the Middle East.

The Ottomans have left their mark across the northern part of the city with a legacy of beautiful buildings. One of the most striking landmarks is the Büyük Han or Great Inn, a restored caravanserai built just after the Ottoman conquest, which is now inhabited by residents selling a rather predictable mix of handwoven carpets, lace, wooden toys, beads and reprinted black-and-white postcards. Their stalls sit under wide archways around an open courtyard with a domed fountain for ablutions in the centre, and would once have been full of the noise of travelling merchants and livestock, with guestrooms on the upper floor. The cleanly swept stone building is in stark contrast to the nearby Kumarcilar Han, or Gamblers' Inn, which still languishes behind tarpaulin and steel fencing, perilously close to collapse, or so it seems. We peer into its dark spaces, keen for a glimpse of a less sanitised, more intriguing past and walk away slightly disappointed.

Guided by the same impulse, I step down from street level into the squatting Büyük Hamam or Great Baths, a two-minute walk from the inns and built in the same distinctive warm yellow stone. The baths offer some modern treatments, such as a half-hour coffee peel, and honey and salt scrub (€30; Dh150 each) as well as a classic scrub down in the Turkish style on a heated marble slab in a steaming room. There's only one patron, a man who welcomes me so enthusiastically wearing only a towel that I step outside again rather hurriedly. A woman beckons me back in and offers me a tour of its exemplary facilities but, once again, the perfection of the restoration leaves me cold.

Of course, I'm looking for a sense of history and authenticity in the wrong places. Constrained by the demands of sightseeing in 35-degree heat with a toddler, I'm dashing to must-see attractions marked on the official tourist map when the black-and white-postcards from the Büyük Han, showing undated scenes from the city before it was divided by modern-day politics, offer a better guide.

The narrow streets in the North Nicosia of today are dominated by thin shop fronts, littered with sawn-in-half mannequins modelling fake sportswear and tourist shops selling the kind of tat that you can buy anywhere. Look over the shoulders of loitering vendors and you can see the twin minarets of Selimiye Mosque, perched on top of what was once known as St Sophia Cathedral, a huge French Gothic monument completed in the early 14th century, which is the city's central mosque. Mashrabiya now fills the high arched windows instead of stained glass. It's a familiar and rather practical transformation, repeated across northern Cyprus, and the cool, lofty whitewashed interior invites contemplation no matter your religion.

The same distinctive views appear in my "old" postcards but the streets are free from tired commercialism. Instead, bearded men dressed in ethereal, glowing, white robes, gather on the street corners under tall, heavily topped palms. These trees still shade parts of the Old City and, away from the main thoroughfares where the shuttered buildings are dilapidated - some seemingly beyond repair - an imperfect, more telling history resides.

One worthwhile stop is the Dervish Pasha Mansion, a restored early 19th-century merchant's house with blue shutters built around its own leafy courtyard in the Arabahmet quarter, where there's also a traditional Ottoman-style domed mosque built some 200 years earlier. The mansion now houses an Ethnographic Museum, and its collection of clothing, agricultural implements and "way we were" room sets is not very impressive but that rather misses the point. Compared to the handful of immaculately restored buildings, the result of EU funding, that are offered up without any point of reference, information boards or official guides, at least here I have a sense of the richness of a culture both literally - thanks to the scale of the living quarters with their colourfully painted ceilings - and metaphorically. In short, I've finally learnt something.

The short walk, some 60 metres, across the UN buffer zone known as the Green Line and into the capital of the Republic of Cyprus reveals a very different story. We're almost immediately greeted with a huge Starbucks coffee shop and a panoply of international high-street brands almost entirely absent from northern Cyprus. There's a sense of dynamism in this part of the city, and orchestrated purpose, not least in the tourist infrastructure. Take the impressive Municipal Museum of Nicosia, the Leventis (www.leventismuseum.org.cy), with its up-to-date CGI tour of life in the old city and sympathetically lit cases of jewellery, clothing, maps, ceramics, everyday objects and art from each historical period. The Venetian walls on this side of the Green Line are showcased by the wide space of Plateia Eleftherias, kept clean from invading plants and seemingly fatter here, thanks to southern prosperity. There are billboards announcing that the starchitect Zaha Hadid intends to transform the square and, as her website puts it, "reconnect the ancient city's fortified Venetian walls and moat with the modern city beyond". The landscaped park area is intended to be a "catalyst", it says, to unify north and south Cyprus, but it's unlikely that an architect's imagination can work wonders where generations of politicans have failed.

Heading out of the city, our next stop is the north's Karpaz Peninsula, a teasing pinch of land to the east of the island, known for its wild donkeys, patchy electricity supply, undeveloped beaches and ... well, nothing else. The drive from Nicosia to Dipkarpaz, one of the last dots on the map before the Apostolos Andreas (St Andrew's) Monastery and the roaring sea, takes about three hours and the scenery quickly becomes depressingly familiar. Empty roadside housing developments, advertising hoardings promising great prices on said housing developments, half-finished commerical properties and Pepsi-branded restaurant signs mark the roadside until the broad tarmac road passes a new super-yacht marina and abruptly narrows to a bumpy two-lane track lined with grass and flowers. The end of tarmacked civilisation marks the beginning of the nature reserve that promises to save much of the peninsula from the concrete blight that flourishes elsewhere.

Dipkarpaz turns out to be an unremarkable-looking place spread around a silver-domed mosque, petrol station and a few grocery stores. First impressions are unpromising - one storey buildings with ramshackle gardens, cars and coaches rotting in the fields and ducks crossing ahead - belie the warmth of the welcome that we receive at Karpaz Arch Houses.

We're shown to one of 17 large guestrooms clustered around a courtyard and colourful garden; a walking group is just back from the day's ramble and, later that evening when we sit on the steps outside our room watching bats whirl and tumble overhead, enjoying cheap but tasty mezze from the restaurant next door, I congratulate myself on a glorious find.

In the few days that follow, the shine is only dimmed by the state of the beaches. In spite of clear, turquoise waters, each cove we visit here, as elsewhere in the north, is littered with plastic and other rubbish, and digging with my daughter in the sand, we both manage to leave sun-kissed but tarnished with spots of sticky oil. I try to talk about the state of the environment with a man who's collecting a nominal fee for the use of the parasols and plastic sunloungers on the beach but he simply smokes, shrugs and walks off. Undeterred, we spend the day searching rockpools for crabs and tiny fish just below the ruined 12th-century church of Agios Filon, where coach parties stop to admire patches of mosaic broken by wild flowers, and the remains of a Roman harbour.

The next day we drive to the other side of the peninsula to visit Golden Beach, reportedly the island's finest; a long stretch of sand broken only by a few boardwalks leading to a low-key campsite with cabins and a cafe. On the way we pick up a Turkish woman walking on the road, beach towel tucked under one arm. She tells us that she has been visiting friends in Dipkarpaz for more than 10 years. "They don't understand what they have here," she says of the residents. "They want big hotels and casinos. I keep telling them to stick to small bed and breakfasts, but it is no good."

Golden Beach turns out to be as beautiful as advertised, and although I return blackened with oil, even that cannot detract from the wild serenity of the place. I leave hoping the residents do not get their way and invite the diggers in, but can you really blame them for wanting to join the rest of the world?

[ cdight@thenational.ae ]

If You Go

The flight Emirates (www.emirates.com) flies from Dubai to Larnaka in the south of Cyprus from Dh2,430 return, including taxes

The stay A double room at the Karpaz Arch Houses (www.karpazarchhouses.com; 00 90 392 372 2009) costs €50 (Dh250) per night, including taxes and breakfast