Egypt may not have a fully functioning government but Cairo airport's shiny new terminal three, opened by Hosni Mubarak in 2009, is working like clockwork. It's the first day of the first round of elections, and dozens of people have been killed in fresh clashes, but immigration officials greet us like old friends.

We're flying straight on, in any case, to Luxor, but some of the hardy group of British, French and German passengers have spent time in the capital without incident. "We've been in Cairo for three days and had no problems," said David and Veronica Turner, from Sussex, England. "At the Egyptian Museum, we had Tutankhamen's treasure room all to ourselves."

The EgyptAir flight south is half-full; from Luxor airport it's a 10-minute taxi ride to the tatty Corniche, where my boat is waiting. Small queues have already built up around polling stations and armed police are stationed in jeeps, yet there's no hint of the violent clashes that have been seen in the capital. Though potentially lawless, it seems that most of Egypt is still held together by a basic moral code lost in many parts of the world.

The Sanctuary Nile Adventurer is guarded languidly by a single armed security guard, and inside I'm greeted with fruit juice and cold towels. "Everything is quiet here," says the boat's smooth-talking captain, Ahmed Talaat. "Even in Cairo it was only a million people who were demonstrating. We are 84 million people and we respect the military and the prime minister."

Still, the unrest has put a huge dent in what is normally the country's prime tourist season. Of the 300 boats that normally ply the waters between Luxor and Aswan, just 70 are currently operating; on mine, 23 people occupy 32 cabins during my four-night cruise, just half the normal number.

There are 14 Americans, six French and three Britons including myself, and we're split into groups based on language and nationality. Me and a British couple, the long-term expatriates Christine and Alan, are allocated our own Egyptologist, 35-year-old Mohamed Ezzat, for the entire trip. My companions have lived in countries including Brazil, Venezuela, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Mozambique, so haven't been put off by a few riots.

There's a lot to see in Luxor, so we begin that afternoon at the Karnak temple, which is much quieter then when I last visited two years ago. Then, it was impossible to get any photos of any of the temples without people in them: this time, groups ebb and flow. Once inside, Mohamed begins to tell us at breakneck speed that Luxor, meaning royal palaces, but referred to in ancient Egyptian texts as Wasat, perhaps meaning power, and also known as Thebes, "was the capital of the New Kingdom of Egypt, which lasted for 500 years. These precincts were mostly built between the reigns of Amenhotep I and III and dedicated to the god Amun-Re and Mut, the sky goddess..."

It's all good information, but even on a second visit it's impossible to take in his summary of the dozens of pharaohs who contributed to building on the site, the stories behind Tutmoses I's two obelisks and the various theories of the festival of Opet. I wander off, contenting myself with the temples' visual attributes and atmosphere: it's as much as I can do to finally get my head around the present layout of the site, with its towering hypostyle hall, obelisks, series of pylons, sacred lake and various ruins, before it's time to leave.

As the sun sets, Mohamed more succinctly describes the ancient Egyptian rulers as a powerful but ultimately doomed cult. "These were temples of eternity built to last forever," he says. He points to a crane. "Yet 3,500 years later, they still haven't finished." Looking at the scale and exactness of the project and the hardness of the sandstone, it's hard not to be impressed by the monumental ego of its creators. Yet when we see portions of painted ceilings and lintels that have kept their colour for all this time, and the almost contemporaneous carved depictions of the rulers and their wives or consorts, there's a touching, human side to it, too.

It's twilight by the time we reach the Luxor temple, originally connected to Karnak by a three-kilometre-long avenue lined with sphinxes. Situated in the centre of town, it's exquisitely lit, and the atmosphere as we wander past its relatively modern-day mosque to the graceful inner sanctuary, the sounds of a wedding party filtering in from the surrounding area, is memorable.

Our first night on the boat is spent docked: after drinks in the lounge and an 8pm dinner we sink into sleep. The boat's size means that inside it feels more like a hotel, with good-sized rooms equipped with a comfortable bed, flat-screen TV, air conditioning, desk and private bathroom.

When I wake at 5am the boat has turned round and I'm looking out over green fields to the hills of the West Bank. We board a small boat to cross the river to visit the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens, the rulers' elaborate burial sites. We arrive at the first just ahead of a large coachload of tourists on a day trip from Hurghada, who catch up with us at KV62, the tomb of Tutankhamen.

Mohamed warns us not to be disappointed, explaining that the young king's burial place is famous not because it was the grandest but because it was the only one found nearly intact when the English archaeologist Howard Carter revealed its location in 1922. Yet even then, he was not the first. "Just 250 years after the burial the tomb was robbed," says Mohamed, "probably for the alabaster filled with perfume. It was re-robbed 3,000 years later." The black-and-white images of the piled-up wooden furniture which was found in one of the temple chambers contrast almost farcically with the huge granite coffin and brightly coloured wall paintings in another. The latter is full of the mystery of the afterlife while the former looks like the contents of a Victorian jumble sale.

The stark valley is riddled with dozens of tombs, which leads to a discussion about construction efforts, but Mohamed is irritated at any suggestion that the ancient Egyptians used slaves. "The workers worked for eight hours a day with one hour for lunch and two days off," he says. "They were paid in kind because there was no money then. They went on an eight-day strike in the Valley of the Kings in 1,100BC and they got everything they asked for. They had lots of rights."

We move on to the Valley of the Queens, the burial site for queens and some of the royal children from the 19th and 20th dynasties. Many are unfinished or anonymous. Tour guides aren't allowed inside any that are open to the public because of the noise levels they create, but arguably this is where they would be most useful since the tomb's official guards hassle visitors but teach them nothing. We emerge from one tomb to find Mohamed pointing out the location of the tomb of Nefertari, Ramses II's favourite queen. "For sure this is the most beautiful tomb in all of ancient Egypt, the biggest and best preserved," he says. "And it is closed. But if you have 2,500 British pounds (Dh14,500) you can visit it for 20 minutes." We're slightly put out that the best tomb isn't open to normal visitors, but we make do with the tomb of Amonchopeshfu, the son of Ramses III, which has startlingly well-preserved wall paintings. "Look, Amonchopeshfu is high fiving Anubius!" says an American - and it does look just like that.

Before heading back to the boat we stop at Deir el-Bahri, built by Queen Hatshepsut, one of Egypt's most famous female pharaohs, who ruled for 20 years. It's here that the Luxor massacre took place in 1997, and as the site fills up with a few hundred tourists, it's hard not to imagine the panic of that day. Its restoration is almost too perfect, but the views back across the valley to Luxor compensate.

The boat sets off to Esna, 55km to the south, and immediately we're in an agrarian landscape. We move onto the top deck to relax and revel in the slow silence of the journey. Travelling at just 16 kph, we can hear the braying of donkeys and echoing call to prayer and spot children playing and women washing on the riverbanks. We see no other large boats and just a handful of feluccas and fishing boats.

We dock on Esna's waterfront and walk through the ancient but empty souq to the Greco-Roman temple of Khnum. Its base is nine metres below street level, having been covered in centuries of silt, making the site a dramatic central point in the small town, but it has still only been partially excavated. It has an impressive pillared facade and inside is a well-preserved but pigeon-filled great hypostyle hall built during the reign of the Roman emperor Claudius. On our way back to the boat we wander the town's small dusty streets and admire the faded glory of its 200-year-old houses before turning back to the boat for lunch.

The boat moves on straight away to Edfu, where we're met on the Corniche by a fleet of horse carriages that take us through the town to the temple of Horus, "the falcon king-god of space, and king of the earth", according to our guide. The temple sits in a mud brick enclosure, and once inside Mohamed delights us with an animated narration of the story of Osirus and the battle between good and evil depicted on the outside walls. He tells us how Osirus was killed by his brother Seth, the god of evil, put in a casket and sent down the Nile only to land in present-day Lebanon before being cut into pieces and buried all over Egypt. "His wife spent two to three hundred years finding and collecting the pieces, and she got the king back to life for one night to conceive their son. Osirus then went to the underworld but his son Horus sought revenge, battling for years to finally keep evil down, with his mother behind him."

Many of the bas-reliefs and carvings strike me as pure propaganda and brainwashing, and Mohamed confirms that heavy censorship and bureaucracy meant that many of the works were not finished. "It took up to a year for the carvings to be approved by which time the king could be dead or deposed."

After afternoon tea we sail on to Kom Ombo, 50km north of Aswan, again relaxing on deck and watching an Egyptian cookery demonstration by the boat's chef on the way. We visit the temple, dedicated to the crocodile-god Sobek and Horus, and dramatically situated on a bend in the river, after breakfast the next day.

Until the building of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960s, Mohamed says, this part of the Nile was still infested with crocodiles, worshipped 2,000 years ago and kept captive, consulted as oracles and eventually mummified within the temple as it was believed they devoured the evil personified by Seth. Kom Ombo was also a medical temple, used as a hospital and featuring possibly the first depictions of medical instruments including scalpels and forceps, and graphic representations of healing and surgery. Some of the patients had to wait for days, Mohamed explains, pointing out 2,000-year-old doodles on the flagstone floors.

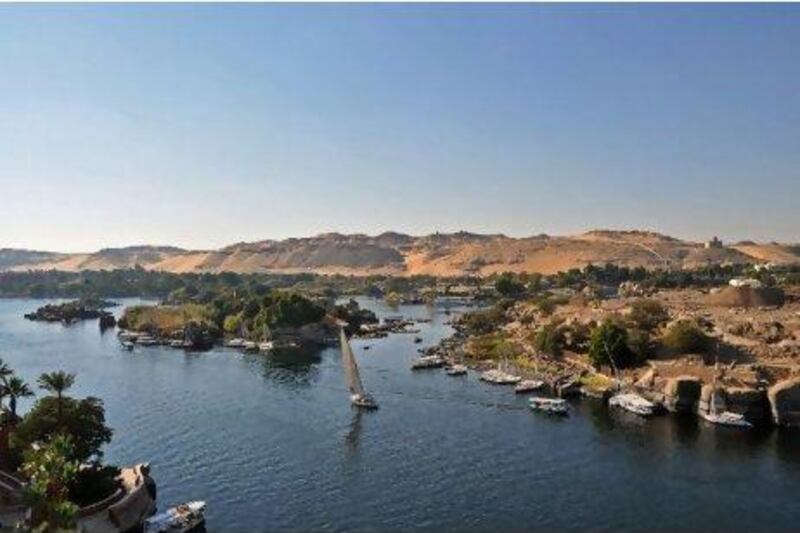

Between Kom Ombo and Aswan the river valley flattens out and the landscape becomes more arid, with fewer fields and giant sand dunes and pale hills towering over small Nubian towns. It's starkly beautiful until we get to Aswan, which is at once unsightly and beautiful with its river filled with sailing boats and densely built-up, ageing Corniche.

We dock after lunch and take a short motorboat ride to the exquisitely symmetrical temple of Philae, painstakingly relocated just before the damming of Lake Nasser would have submerged it. Mohamed tells us that Cleopatra's Needle, now sitting beside the Thames in London, was moved from Philae by Giovanni Belzoni, but this is contradicted by the Encyclopaedia Britannica, which says it came from Alexandria.

Some of the west-facing figures in the temple were defaced by early Egyptian Christians, but, as Mohamed says, "it could have been worse" since figures that were out of reach of those on ground level are still intact. "Not a theory but almost a fact," Mohamed says of the way the various faces of Hathor, Horus' mother, get madder as you walk toward the temple of her mother-in-law.

We return to Aswan via the site of the "unfinished obelisk", a huge granite quarry containing several huge obelisks half-carved out of rock. "All obelisks from ancient Egypt came from Aswan as it's the hardest stone," Mohamed says - so perhaps, Cleopatra's Needle came from here after all.

And with that the cruise is finished. I check into the Sofitel Legend Old Cataract, newly opened after a $100 million (Dh3.67m) renovation. The hotel dates from 1898 when the first Aswan dam was being built. Agatha Christie stayed here in 1937, writing part of Death on the Nile from her first-floor suite. The grand red and white Victorian exterior with its black iron balconies has been preserved, while the palatial Moorish interiors have been brightened up with new flooring, drapes and some remodelling; the rooms themselves have been more thoroughly overhauled. Still the framed photographs of dozens of famous alumni line the corridors.

The views from my window across to Elephantine Island, with its dark rocks, still water and graceful feluccas, is just as Christie described it. This whole trip, I realise, has been to experience the golden age of Nile travel in something of the same way - even more so at this hotel, which is just 20 per cent full when I visit.

Yet there is one final adventure. I book a day trip to the most impressive temple of all, Abu Simbel, which involves a 30-minute flight south from Aswan. We fly over Lake Nasser, scattered with small islands, and I'm met at the airport by Mohamed Ibrahim Al Kader, a guide who, like most, has his own way of telling things. "Ramses II was king of the desert," he says on our way to the four colossal statues and nearby temple of his beloved wife Nefertari, both moved at a cost of $40m (Dh147m) - again, to escape flooding. "It was situated here for political, economic and geographical reasons. Ramses wanted to control the southern border and the gold mines of Nubia... but he pretended he was god." He also ruled for 67 years and had 164 children.

Because I booked a private transfer from the airport, I get to the temple's facade ahead of two other groups and see the set of four figures, 30m high and 38m wide - alone, with only the wind whistling off the sparkling lake for company.

It can't be long before the Nile temples fill up again, I think, looking inside at the deeply carved bas-reliefs of battle scenes that make the figures bristle with strength and power. The kohl around the eyes of the women on the wall paintings and Nefertari's translucent dress are just a fraction of the details on offer - and in silence, without the crowds, you can imagine you're right there with them.

If You Go

The flights Etihad Airways (www.etihadairways.com) flies return from Abu Dhabi to Cairo from Dh1,250 return including taxes. EgyptAir (www.egyptair.com) flies from Cairo to Luxor and Aswan to Cairo from Dh1,040 per round trip including taxes.

The cruise A four-night cruise on the Sanctuary Nile Adventurer (www.sanctuaryretreats.com; 0020 22 393 5450) costs from $391 (Dh1,435) per person per night, including all meals, sightseeing and transport. There is a 25 per cent discount for bookings made before February 29.

The hotel Rooms at the Sofitel Legend Old Cataract (www.sofitel.com; 0020 97 231 6000) cost from $472 (Dh1,733) per night including taxes. A day trip to Abu Simbel costs from $300 per person including flights, private transfers, a guide and entrance fees.