When I first started planning my journey with Herodotus, the fifth century BC Greek "Father of History", I never thought we would end up in war-torn Iraq together. Herodotus was the author of the magisterial Histories, a one-volume masterpiece on the Persian Wars and the world's first ever history book. Although we may not be able to say with precision exactly where Herodotus travelled, from his first-hand accounts we can surmise that he explored Turkey's Aegean coast, her great cities of Ephesus, Miletus, Priene, Halicarnassus, Pergamum, Sardis and Smyrna. We know he sailed among the Greek islands and spent a great deal of time in Samos and Athens. He visited modern Lebanon and Iraq and probably travelled through Libya. After a monumental journey, or journeys, in Egypt he seems to have retired to the heel of southern Italy where he probably wrote his Histories towards the end of a remarkable life.

Herodotus appealed to me because he was the consummate travel writer: fearless, humane, highly tolerant, hugely entertaining and consistently amusing. His interest in, and respect for, foreign cultures marked him out as ahead of his time, an early multiculturalist if you like. Turkey was on my itinerary because the Aegean resort of Bodrum, the Halicarnassus of old, was Herodotus' hometown. Egypt was a must, too, because this was the country that most captivated him with its temples, pyramids, its unfathomable history and the many mysteries of the Nile. Greece was a given, not least to visit the battle sites of Thermopylae, Marathon and Salamis that he made famous in the Histories, his masterpiece on the Persian Wars.

Yet as I flicked through my atlas, charting a journey across the splintering backbone of the Taygetus mountains in the southern Peloponnese, to jaded Sparta and faded Olympia, the tumbled columns of Corinth, divine Delphi and dreamlike Athens, I couldn't stop turning to Plate 35 and there it was: Mesopotamia, the beginning of the world, the birth of civilisation and the dawn of history. Hemmed in by the Tigris and the Euphrates, Babylon dared me to visit. On the atlas it was irresistible (my Oxford English Dictionary called it "the mystical city of the Apocalypse") but in 2004, with Iraq mired in bombings, beheadings and bloodshed, it seemed a step too far.

As Herodotus wrote, "No one is fool enough to choose war instead of peace - in peace sons bury fathers, but in war fathers bury sons." In the event, the temptation to visit proved overwhelming. My first experience of Baghdad was faintly terrifying. Hot metal and blinding light. 44 degrees Celsius. Hairdryer wind. The roar of generators, jet engines and machinery. Palm trees swirling through the shimmering waves. Black Hawk helicopters overhead, blades ripping through the air, dust clouds surging in the downdraft. I was met by two Americans festooned with weapons and gadgets. Black M4 rifles were suspended from clips on their chests, already bulging with magazines, medical packs, identity badges, combat knives and radios. Glock 17 pistols in their thigh holsters. Tactical combat trousers covered with pockets. The welcome greeting was unusual.

"Our route into Baghdad today is dangerous. The bad guys have been attacking it a whole lot recently. They may attack us today. If they do, we have B6 armour in these vehicles to protect us. It will stop automatic fire but it will not stop RPGs or VBIEDs [vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices]. If one of the Toyotas goes down, you are to stay in your vehicle. Do not attempt to leave the vehicle on your own. I repeat, do NOT attempt to exit the vehicle. This is the way to get killed. Our journey should take us around 12 minutes. Wear your body armour and helmet at all times."

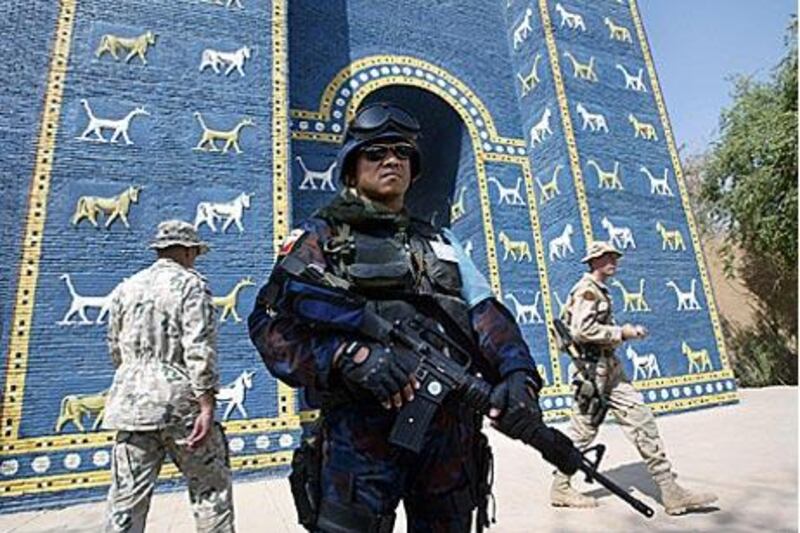

Over the course of the next year, I travelled this 11km stretch of road - fondly known as "Ambush Alley" and "the most dangerous stretch of road in the world" - numerous times. One of the most memorable experiences in Iraq was a private tour of the National Museum, then closed to the public, by its director Dr Donny George, subsequently pushed out by the Mahdi militia. My abiding memory is of dust and closed doors, locked gates and sealed storehouses. We ambled through neglected galleries, shafts of sunlight lancing through the gloom, past some of the greatest artefacts ever culled from the Muslim world, fruits of Islamic jihad when Baghdad was the illustrious, sparkling-domed capital of the Dar al Islam, seat of the Abbasid caliphate from 762-1258. When Herodotus wrote about Babylon, his account was filled with amusing - some of it undoubtedly exaggerated - detail about the medical and sexual customs of the Babylonians. My experience of the fabled city was a more sombre business. I was fortunate enough to spend an afternoon at the site with Agnieszka, a Polish archaeologist, just before the coalition handed the damaged site back to the Iraqi government. We began next to the Ishtar Gate, treading in the serially victorious sandalled footsteps of both the Persian Great King Cyrus and Alexander the Great, who took Babylon in 539BC and 331BC respectively. Sections of the Processional Way, having shed their glazed revetment, glowed in the bullying blaze of light, giant teeth of sun-burnt bricks decorated with Nebuchadnezzar's dragons and bulls. One of the dragons was missing a large chunk of its neck, a painful example of the looting that took place after Saddam's fall. "What happened here is a crime," Agnieszka said. I stared across the remnants of the city, besieged on all sides by a foreign army of occupation - tents, temporary accommodation, armoured vehicles, helicopters, soldiers - searching for the Tower of Babel, even though I knew it had long gone. Much of what remained was Saddam-era restoration, Disney for a despot. Everywhere were reminders to visitors: "This was built by Saddam Hussein, son of Nebuchadnezzar, to glorify Iraq." A young American Marine in desert fatigues approached us as we prepared to leave. "Excuse me, Ma'm, I got a question for you," he said to Agnieszka. "Which way's the Hanging Gardens?" The four-year odyssey with Herodotus ended, appropriately enough, in his homeland of Greece. In Athens there was a cross-cultural encounter between Greek and Iranian scholars discussing Ancient Greece and Iran, an intellectual beginning to a more leisurely drift in the sun-spattered Herodotean slipstream. Many, if not most, of the Greeks I met during a month-long visit were bemused by the concept of travelling in Herodotus' footsteps, judging the modern world by his standards. It is not difficult to understand such scepticism. To Greeks today, Herodotus is just one of many great figures of the fifth century. They are, after all, spoilt for choice. Think of the playwrights Aeschylus, Aristophanes and Sophocles, the statesman Pericles and the historian Thucydides, the physician Hippocrates and Socrates the philosopher, to name just a few. From Athens I sailed to the easternmost island of Samos where I dutifully hacked through undergrowth to find the hidden northern entrance of the Eupalinos Tunnel, a triumph of engineering from the sixth century BC. It particularly wowed Herodotus because it was dug from both ends simultaneously through the side of a mountain, no mean feat to meet in the middle of a 1,000-metre stretch of soil when mathematics was rudimentary to say the least. Samos was also home to the evocative ruins of the Temple of Hera, one of the largest in Greece, and the harbour mole, a quarter of a kilometre long, built by the megalomaniac tyrant Polycrates. No wonder that Herodotus regarded these as "three of the greatest building and engineering feats in the Greek world". Among the tumbledown columns and pedestals and temples of Delphi I argued with a Greek academic friend who described herself as an Aristotelian philologist and warned me not to think of Herodotus as a man but a text. I mooned about Olympia and watched an impromptu exorcism in Thessaloniki. In the northern port town of Kavala I drank whisky with a Greek millionaire and Herodotus devotee who had converted the house of Mohammed Ali Pasha, founder of the modern state of Egypt, into a sumptuous hotel-cum-museum. Later, returning to Herodotus' mesmerising account of the Persian Wars (recently dramatised in the film 300), I retraced the mountainous route of the Athenian politician Ephialtes, whose treachery helped the Persian emperor Xerxes win a Pyrrhic victory over the Spartan king Leonidas and his 300 warriors at Thermopylae in 480BC. Bringing that story to an end, I clambered over fallen stones at Plataea, the battle that brought the Persian Wars to a tumultuous climax the following year. After the rigours of all this historical research, there was time for a final digression in the Peloponnese. Nothing to do with the Greek historian for once, though I told myself Herodotus would approve, with his interest in interviewing war veterans and his passion for travel writing. What better way to finish a long journey than lunch with Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor, war hero and one of the finest writers in the English language? I turned up late, flustered, flushed and sweating horribly. I had been hiking up to the tiny, mountaintop church of Agia Sophia, high above the prickly Viros gorge, past the mythical graves of the mythical Dioschouri, the twins Castor and Polydeuces, sons of Zeus and Clytemnestra, immortalised in the constellation of Gemini.

The housekeeper waved me down a vaulted stone gallery, cool air ruffling through the arches, an architectural reminder, perhaps, of Byzantium, which in a sense was always Leigh Fermor's true north. I stepped into the sort of room to make a writer swoon. The English poet John Betjeman called it "one of the rooms in the world". Whitewashed walls, flagstone floor and panelled wood ceiling framed a space that was both sitting room and library. Bookshelves rose from floor to ceiling. Light streamed in from tall windows thrown open towards the sea. In the garden to the north I could pick out a congregation of tufty cypresses, olive trees and rosemary hedges. Inside, piles of books jostled for space with armchairs, cushions, icons, sculptures, lamps, bowls and boxes, maps, Turkish kilims and flokati rugs of shaggy goats' hair. An alarmingly handsome figure was sitting in the sun-bleached garden room a step down from the library, clasping a Loeb edition of Herodotus. A more debonair specimen of the literary warrior would be difficult to imagine. "You've kept me up till 1.30 in the morning with this," he said breezily, waving Herodotus in front of me. "I've been reading about the battle of Marathon." Later, after our Herculean lunch was over and we were saying goodbye, he led me to another building, half hidden by the olives and cypresses. A fleeting glimpse into his writing room and inner sanctum: papers everywhere, more zigzagging stacks of books. His hero Byron stared at us from a plate in the centre of a broad chimney piece. Then the door closed and the momentary magic spell was over. "Do drop in again if you're ever in the area," he said. Mentally, I started making plans to leave my wife and become his amanuensis. Justin Marozzi's The Man Who Invented History: Travels with Herodotus is published in paperback by John Murray this month.