What would the average expatriate in the UAE do if handed a free spa coupon? According to the popular stereotype, a Jumeirah Jane would quaff her Lime Tree Cafe latte with indecent haste, then rush off in her Range Rover in pursuit of the latest dose of indulgence. But the truth is not that simple. Despite the attention devoted to the instant-gratification generation, which has been blamed for everything from the global financial crisis to global warming with its desire to have everything now and pay for it later, there is a flip side, if the latest research is any clue.

Less visible are those who defer gratification, sometimes to the point of missing out on it altogether, and the UAE's expatriate population has a self-selected bias that way. For the subcontinental labourer and highly qualified western professional alike, living in the UAE inevitably requires spending time away from loved ones and the familiar lives of their homelands. As a rule, such people take the view that the higher incomes here will buy a lot more freedom, comfort and options when they eventually return to their countries of origin, whether to a modest home in Kerala or a beachside mansion in Bali.

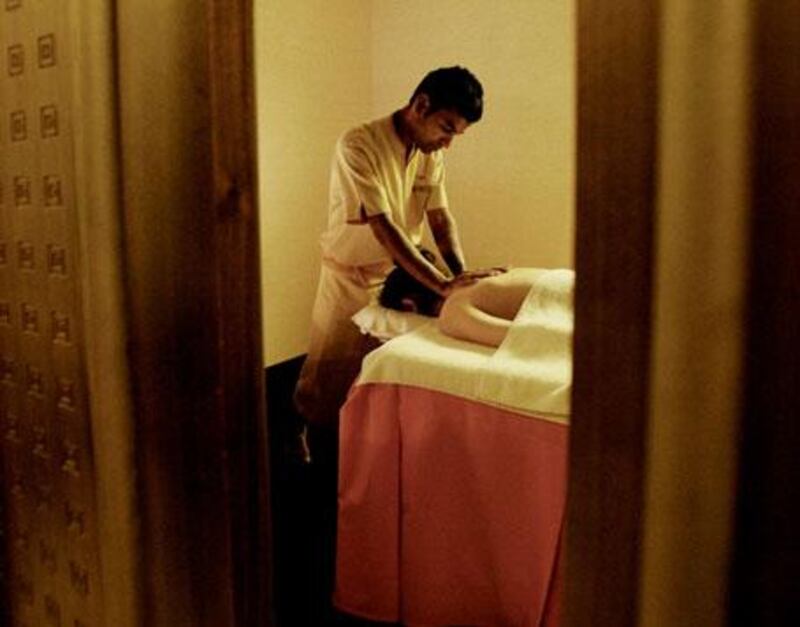

So what would they do with the free spa coupon? According to Suzanne Shu, a behavioural economist at UCLA, there is a significant chance that it would be put aside for use later, with a high chance that it would never be used at all. The uniquely human habit of procrastinating when facing unpleasant tasks is already well established, with the principle being that the short-term benefit (eg, lazing around watching television instead of going to the gym or a student having a party instead of studying) outweighs the long-term consequences (poor grades or failing to lose weight).

But Shu believes there is a similar procrastination that affects pleasurable activities, such as having coffee and cake, a night at the movies or a spa session. This paradox of deferring pleasurable activities became the basis for her PhD dissertation, in which she tested hundreds of her countrymen to assess their approach to gratification. When she gave out movie vouchers that were valid for two weeks, she found that just under half (49 per cent) would be redeemed before they expired. But if they were valid for six weeks, only a little more than a third (35 per cent) would be used.

Similar tests of vouchers for a spa session and for coffee and cake showed similar results. Her theory is that most people tend to assume that in the future they will have time to use the voucher, only to find their lives as busy as ever. Another take on the findings is that some people always want to have something in reserve for a rainy day when life might be more difficult. This human habit is well known, if not publicised, by retailers because every year billions of dollars worth of vouchers expire or otherwise go unused, creating instant profits.

Almost everyone knows of a situation where someone has worked without holidays for years, intending to take a lavish world trip when they retire, only to fall seriously ill or even die before then. There are more everyday examples of deferring gratification, such as not using the best china in case it gets chipped by use or keeping air miles for an important trip in the future. When The New York Times publicised Shu's findings, it sought readers' comments and received one from a woman who described her husband as "a frugal, intelligent, cautious man who made choices carefully, researched his options, weighed the cost versus benefits of any situation and generally erred on the side of saving money, time, and energy for later.

"He died when he was 35 years old with money in the bank and all his bills paid. He loved to ski but hadn't done any skiing in years. He was waiting, who knows what for? "It was the only request he made of me before he left the planet, that I be happy. If you can't seem to allow yourself joy for your own sake, do it for someone who can't do it for themselves - a friend or loved one who is in the hospital or sick, or dying or gone. Do it in celebration of them and the life they didn't get to live fully."