One was an Italian aristocrat born in a Roman palace, the other is one of 11 children of poor Algerian immigrants, raised on a notorious French housing estate.

But 123 years after Schiaparelli’s birth, nearly 60 years since her fashion house closed and 40 years after her death, her legacy has been embraced by the woman who cheerfully calls herself “the girl from the banlieue [immigrant-dominated suburban France]”.

The House of Schiaparelli has been resurrected, Khelfa is its ambassador and the Italian designer Marco Zanini has arrived from Rochas as the creative director.

“I cannot tell you how exciting this is,” says Khelfa. “We have brought a beautiful name back to the heart of Paris.”

Zanini’s first creations for the revived house, based in the chic Place Vendôme, will be paraded at haute couture week in January. The sharp, critical eyes of the fashion world will be fixed on the catwalk.

So many years have elapsed since Schiaparelli was in her pomp that it is easy to overlook her influence. One London fashion writer wrote that her “squared-off shoulders and nipped-in waists” gave the world the power suit just as Chanel created the “little black dress”; Khelfa laughs, but sees a valid comparison.

“Schiap really was the hippest thing,” she says. “The blouse with a zip down the back as early as the 1930s, the perfume bottle in Mae West’s shape, camouflage as fashion wear … she was a stylist who understood her time. And you find a little bit of Schiaparelli in every fashion house.”

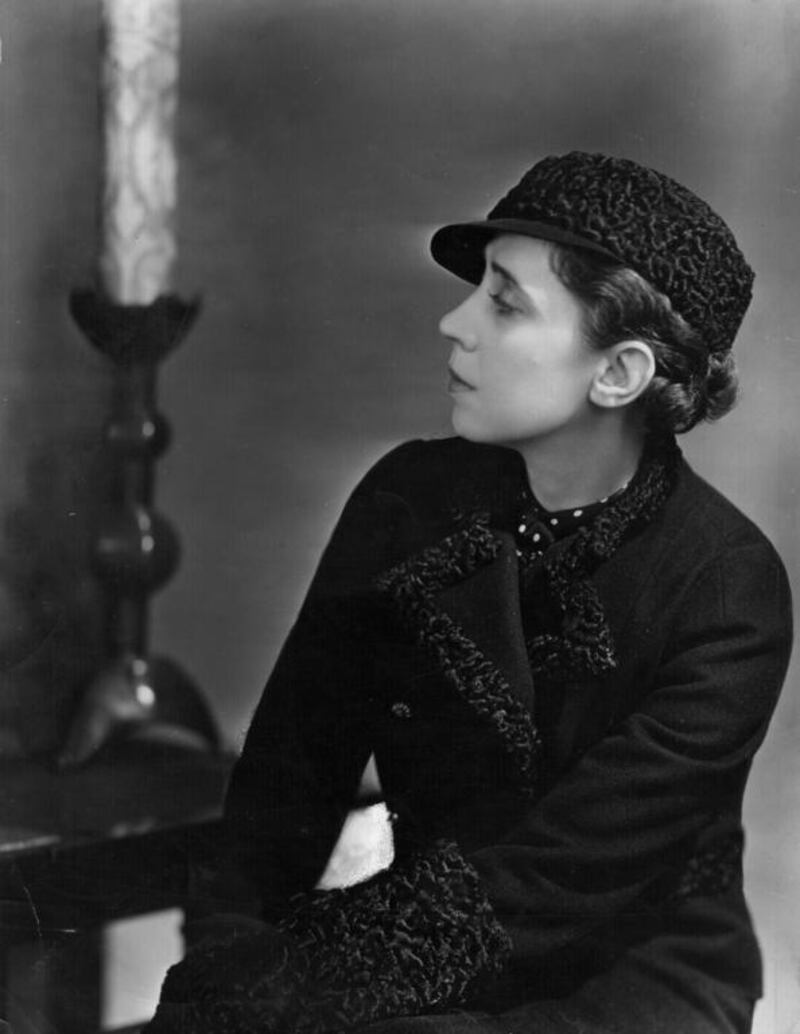

Khelfa, 51, knows all about glamour. She was France’s first Arab supermodel, posing for Jean-Paul Gaultier, Thierry Mugler and the Tunisian couturier and shoe designer Azzedine Alaïa.

She went on to act in films and, later, to direct them. In 2011, she made a documentary in post-revolution Tunisia, determined to show educated, articulate Muslims far from the stereotype of western media. “I remain optimistic. The example of the French Revolution shows you cannot build a democracy from one day to the next.”

Between other career interests and motherhood, she also spent seven years helping to run the Alaïa business. And now her role in the bold plan by Diego Della Valle, the head of the Italian leatherwear company Tod’s, to re-establish Schiaparelli is attracting international attention.

This is not what she can have expected, fleeing at 16 from a home life she found stifling. Her father, an illiterate railway worker, resented her love of books. Her mother could read but, with her husband, struggled to accept modern ways in a country where they felt like unwelcome strangers. An elder sister had already moved to Paris. Khelfa joined her, met Christian Louboutin, later one of the world’s best-known footwear designers and soon had her introduction to a new world.

These days, her address book is the envy of many. Mick Jagger, the frontman for the Rolling Stones, and Bernadette Chirac, the wife of Jacques, the former French president, were at her wedding a year ago to Henri Seydoux, the son of one of France’s top business figures, Jérôme, the owner of Pathé. Her stepdaughter is the acclaimed young actress Léa Seydoux; Khelfa and Carla Bruni-Sarkozy were witnesses at each other’s weddings.

It is, she recognises with a chuckle, a long way from Les Minguettes, a drab quarter of Vénissieux, south of Lyon, best known as the starting point of the 1983 March of the Beurs, a powerful symbol of Maghrebin demands for equality.

Khelfa may have left Vénissieux behind, but she does not dismiss it as if it never existed. “I’m married to a Frenchman, he tells me I am French but I don’t feel completely so, because I have this huge heritage, not just from the Maghreb but the Arab and Muslim world generally.

“I don’t see myself as Algerian but even with close European or American friends, I know I’m different. I’m comfortable with this; I prefer being of the minority.”

Two siblings died in infancy. Her father is dead and contact with her mother and other relatives is patchy. She has visited Algeria only twice, at the ages of 10 and 14, though she would like to go again.

The feeling of being different, she believes, helped drive her towards making something of her life. “But I am not a role model. I did what I did. Zinédine Zidane [the French-Algerian former footballer] did what he did. He would have been Zidane without me.”

Along with the birth of her two sons, she identifies leaving home as the most important event of her life.

And now, a great new challenge looms. She sees Zanini’s creative flair, described by The New York Times as “elegant, if slightly quirky”, as an exciting weapon in the battle to re-establish Schiaparelli as a fashion force.

“He is a talented designer who understands the Schiaparelli DNA,” she says. And the House of Schiaparelli 10 years from now? “Back among the world’s most important haute couture names.”

[ artslife@thenational.ae ]