In the beginning, beyond a brief article in Canada's The Globe and Mail, there was almost no fuss.

"A man who lost his left leg to cancer three years ago says he hopes to run about 50 kilometres a day on his way across Canada," reported the newspaper on April 14, 1980.

The short report had even got the wrong leg. In fact, Terry Fox, from the city of Port Coquitlam, British Columbia, had lost his right leg to cancer, at the age of 18.

Now aged 21, he was planning to run back home across the country from Newfoundland to Vancouver, an incredible journey he hoped to complete by October that year to raise money for the Canadian Cancer Society.

Symbolically dipping his artificial leg into the harbour at St John's, and planning to do the same in the sea off Vancouver - 8,400 kilometres and six months later - he set out on April 12, 1980, on his Marathon of Hope.

He never made it. The cancer that had claimed his leg at the age of 18 had invaded his lungs and, within months of forcing him to halt his run just past the halfway point, it would kill him. He died on June 28 the following year.

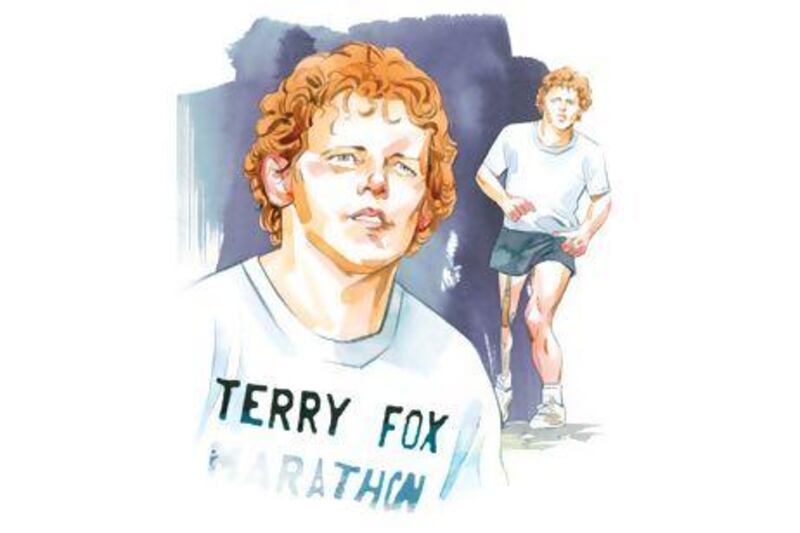

But by the time he was forced to abandon the attempt on September 1, 1980, the freckled-faced, curly-haired young man had captured the nation's hearts.

Today, more than 30 years after Terry's death, his example inspires millions of people across Canada and in some 40 cities around the world, from Abu Dhabi to Zagreb, Croatia, to take part in an annual Terry Fox Run. The man who set out to raise C$1 million (Dh3.6m) for cancer research has been responsible for raising in excess of C$600m.

There was nothing obviously special about the baby boy born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, on July 28, 1958, to Rolland Fox, a railway worker, and his wife Betty, who later described their son as "average" - but determined. With an elder brother, Fred, Terrance Stanley Fox was followed into the world by another boy, Darrell, and a sister, Judith.

At school, Terry, shorter than other kids his age, fought hard to keep up with his peers. He was, according to Bob McGill, the physical-education teacher at his junior school, "the little guy who worked his rear off".

Terry made friends with another boy who, like him, was short and an introvert. The difference, according to a biography published by the Terry Fox Foundation, was that Doug Alward was a talented athlete, good at running and basketball.

It was then, in the eighth grade, that Terry found his determination. When a coach tried to dissuade him from playing basketball because he was obviously so bad at it, it was a red rag to a bull.

He trained like a demon; in his first season he had just one minute of play. Off court, he regularly challenged his friend Doug to some one-on-one and equally regularly took a beating.

But his persistence slowly paid off. By grade 11, Fox was in the starting line-up as a guard for the Port Coquitlam High School Ravens. In one-on-ones, it was now Terry who was regularly pasting Doug. Later, Doug would drive Terry's support vehicle during the Marathon of Hope.

Terry, no more a natural academic than he was a sportsman, applied the same determination to his schoolwork and, graduating with good grades, he went to Simon Fraser University - drawn by the fact that it had the best varsity basketball team in British Columbia.

Planning to become a PE teacher, he majored in human kinetics and made the basketball team. "There were more talented players who didn't make it," a team-mate later recalled, "but Terry just out-gutted them."

And then, on November 12, 1976, Terry crashed his car.

It was a minor shunt that left him with a sore right knee and, with the basketball season to focus on, he ignored the pain until well into the following year. He finally got round to going to hospital on March 9, 1977, where he was diagnosed as suffering from osteosarcoma, an aggressive form of bone cancer.

Within days his leg was amputated, 15 centimetres above the knee.

The night before the operation, his basketball coach brought him a magazine article about an amputee who had run the New York Marathon. "It was then," Terry later recalled: "I decided to meet this new challenge head on and ... conquer it in such a way that I could never look back and say it disabled me."

First, he had to endure 16 months of chemotherapy, a "physically and emotionally draining ordeal". Surrounded in hospital by fellow cancer sufferers, this was the point, he realised, when a person's spirit could so easily be broken forever.

He hatched an audacious plan: to run not a single marathon, but a whole series, back-to-back, day after day, that would take him on an inspirational journey across the entire country.

In the cancer clinic, he wrote in October 1979, in a moving letter seeking the support of the Canadian Cancer Society for his planned run, "There were faces with the brave smiles, and the ones who had given up smiling. There were feelings of hopeful denial, and the feelings of despair".

He could not leave the clinic, he wrote, "knowing these faces and feelings would still exist, even though I would be set free from mine ... I was determined to take myself to the limit for this cause."

Through months of tough training, Terry adjusted to his artificial leg and perfected what would become known as the Fox Trot. And, as he set off from Newfoundland and began relentlessly pounding out the kilometres in relative obscurity, something remarkable started to happen.

Day by day, the sight of this young man, stubbornly ignoring the pain from his often bloody stump, began to capture the imagination and the hearts of a nation. Larger crowds gathered along the route, cheering him on and donating money. When he reached Toronto, a crowd of 10,000 people was waiting for him.

Back home in Port Coquitlam, Terry's parents were telling reporters about their pride in their son.

Even as a youngster, said Mrs Fox, "he set his goals high and he achieved them, because he worked at them". He was not, added his father, "the kind to give up".

But just two weeks later, on September 1, 1980, Terry arrived outside Thunder Bay, Ontario, at the end of a particularly tough 31km stretch, during which he had found it increasingly difficult to breathe. The cancer had returned, attacking his lungs.

In 143 days, Terry had travelled an astonishing 5,373km. He was devastated. "If there's any way I can get out there again and finish it, I will," he told reporters as he lay on a stretcher outside the local cancer clinic, shortly before flying home.

Terry would never run again, but Canadians from all walks of life took up his baton.

"You started it," wrote the CEO of a major hotel chain, in a telegram sent the next day to the Fox family, pledging to stage an annual fundraising run in Terry's name. "We will not rest until your dream to find a cure for cancer is realised."

For The Globe and Mail, in an editorial on September 4, "the peculiar rhythm of that hopping gait [had] worked its way insistently into the consciousness of a nation that is not given to the quick embracing of heroes".

But it took outsiders, in the form of the The New York Times, to see a wider truth. "Mr Fox," noted the paper, had "succeeded in doing what politicians have so far failed to do - bringing a sense of unity to this often divided country".

Money poured in. A telethon alone held less than a week after he stopped running raised $10m and, by February the following year, the Terry Fox Marathon of Hope fund passed $24.1m - one dollar for every Canadian.

Terry lived to see it, but finally succumbed to his cancer on June 28, 1981, exactly one month short of his 23rd birthday.

"He died," said a weeping spokeswoman for Royal Columbian Hospital in New Westminster, British Columbia, "surrounded by love, the love of his family, all of whom were with him, and the love and prayers of the entire nation."

Federal flags were flown at half-mast and honours and tributes flowed in, from the Prime Minister down. "It occurs very rarely in the life of a nation, said Pierre Trudeau, "that the courageous spirit of one person unites all people in the celebration of his life and in the mourning of his death ... we do not think of him as one who was defeated by misfortune, but as one who inspired us with the example of the triumph of the human spirit over adversity."

Schools, roads and even a mountain peak were renamed and stamps and coins were issued to commemorate the "average" boy from small-town Canada who inspired a nation.

But perhaps the tribute that would have meant most to Terry is that every year, in more than 20 countries, millions of ordinary people take part in an annual run in his memory. Between them, they and other fundraisers have raised more than $600m, transforming cure-oriented cancer research around the globe.

"Even if I don't finish, we need others to continue," Terry had said three months into his run. "It's got to keep going without me."

It has, and almost 33 years later, the spirit of Terry Fox is still going strong.

The Biog

July 28, 1958 Born Terrance Stanley Fox

1977 Diagnosed with bone cancer, right leg amputated

1979 Begins training for Marathon of Hope

1980 Sets off across Canada from Newfoundland

1980 Lung cancer forces him to quit after 143 days and 5,373 kilometres

1981 Marathon fund tops C$24.1 million - $1 for each Canadian.

June 28, 1981 Dies

1981 A peak in the Rockies and part of the Trans-Canada Highway named after Terry

1982 Canada Post issues Terry Fox stamp

1990 Canada's The Sports Network names Fox Athlete of the Decade

2005 25th anniversary of run marked by minting of C$1 Terry Fox coin

2013 Donations to Terry Fox Foundation top C$600m

artslife@thenational.ae

Follow us

[ @LifeNationalUAE ]