For Meena Chaudhary, this year will mark not only her sixth wedding anniversary, but also five years since her newborn baby died in the delivery room.

Now in her early twenties, Chaudhary was married at 15 and pregnant by the following year, but a complicated antenatal period coupled with a lack of adequate health care in Nihalpur, her village in western Nepal, meant this young adult's life had already been tainted with almost unspeakable grief before her teenage years were out.

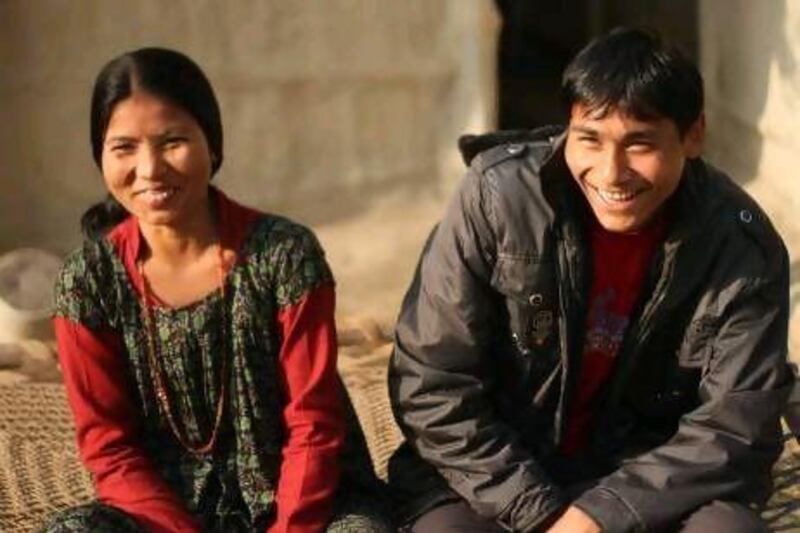

"We didn't even know what marriage was," said Chaudhary's husband Ramesh, who is a few months younger than her, as both of them sat outside their single-room mud-built house. "We didn't know what we were doing."

Chaudhary's story paints a stark picture of conservative Nepal, a country of 29 million people, where traditional customs remain deeply rooted.

According to the latest government report published by the Central Child Welfare Board under Nepal's Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare, 34 per cent of all new marriages in Nepal involve children under the age of 15. Yet, according to Nepali law, marriages involving those under the age of 18 are deemed to be "child marriages" and are illegal.

But in some communities, especially in the south of the country, these numbers are even higher, according to Kirti Thapa, who works at Nepal's Save the Children child protection department.

"The rate of marriage for people under the age of 15 is more than 50 per cent in some communities," Thapa said.

The wedding ceremony itself is considered to be one of the most important rituals in Nepal. It's a social service that holds religious connotations. Folklore would have it that weddings are made in heaven.

"People don't want to interfere and obstruct something good," said Rambhajan Yadav, who has been working in advocacy projects against child marriage in Janakpur, a town south-east of the capital Kathmandu.

Yadav has also travelled extensively and worked in districts like Dhanusha, Mahottari and Rupandehi in Nepal's southern belt, where there is a high rate of child marriage. The statistics from the area, according to Yadav's estimates, are alarming.

"In Rupandehi, 89.5 per cent of girls are still married young, mostly under 18," he said. "The figures in Dhanusha stand at 59 per cent and Mahottari at 51 per cent."

Lack of awareness of the laws, social pressure and the low economic status of the family drive these statistics, Yadav said. In certain communities, the amount of dowry that is due increases in proportion with the girl's age, making parents give away their daughters as early as they reasonably can.

A recent report by Care Nepal, an international non-government organisation, states that more than 72 per cent of families cited poverty as the prime reason for allowing their daughters to marry young. The World Bank index reveals that 55.1 per cent of Nepal's population lives on under Dh5 per day.

But child marriages aren't the only problems of rural Nepal.

Ambika Pradhan, born and brought up in Kathmandu, was married when she was 15. Her family had started looking for a suitable groom two years earlier.

A conservative family, Pradhan's parents did not think it was necessary for their daughter to finish her education once they had found her a husband. Indeed, after she married, she stopped studying.

Experts working in the field of child rights see this as one of the key factors that exclude girls from education.

The adult literacy rate in Nepal for men is 71.6 per cent and 44.5 per cent for women. According to the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2011, of the 7.6 million adult illiterates in Nepal, 67 per cent are female.

Pradhan, who is now 35, also talked about the health problems she faced when she delivered her first child at 16.

"I wasn't aware or prepared for anything," she said of the repercussions of marrying young. "I went through physical and mental problems."

Giving birth at an early age, and after more than 24 hours in labour, Chaudhary lived with a medical condition called fistula for five years which, until corrected, left her isolated from the community.

Goma Dahal, a counsellor for Women's Rehabilitation Centre, a non-profit organisation based in Kathmandu, said that early marriage combined with lack of basic health care results in various complications for women.

In an effort to empower and educate women, Dahal travels to different parts of Nepal. So far she has travelled to more than 50 of Nepal's 75 districts.

A landlocked country crushed by a decade-long insurgency that ended in 2006, Nepal is still in a transitional phase. The new republic is struggling to draft the country's new constitution, which is due on May 27.

But even now that Nepalis are speaking about change and human rights and the concept of a "new Nepal" is emerging, the practices of the past still exist.

Regardless of the various laws that Nepal has against child marriage, child rights experts like Thapa said there is a setback when it comes to implementation.

Laxmi Prasad Tripathi, under-secretary at Nepal's Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare, said that the ministry cannot directly intervene in this issue.

"It's a legal matter and the law enforcement division is responsible for handling the cases," he said.

However, the problem is that people do not report these cases: marriages are community ceremonies and reporting them could not only jeopardise the bride's future but also strain village harmony. According to Save the Children's annual report in 2010, only 30 cases of child marriage were reported in seven districts, a rather insignificant number regionally and nationally.

In some cases, Thapa said that the local law enforcement officials in the region are not aware of the laws.

Also, there are instances when it becomes difficult to ascertain proper documentation as birth and marriages are rarely registered in the villages.

Yadav said the state should be more proactive and criticised the law for being inactive. Though he admitted that child marriage is not specifically addressed in the government's programmes, Tripathi added that a new national policy for children is being drafted and there will soon be a special provision on child marriage.

While this is being done, non-profit organisations as well as local government regulators such as the District Child Welfare Board and the Village Child Protection Committee have stepped up to raise awareness on child marriage.Women like Pradhan, married at an early age, are also talking about the issue in their communities. Pradhan, who now works as a radio presenter at one of the FM stations in Kathmandu, said she raises the issues and discusses on her radio shows time and again.

But while everything is being said and a little done, thousands of girls are still getting married young in remote Nepal where women's rights, health and education are unheard of.

"The customs still exist in our society, and we need to raise our voice against it," Pradhan said.

Bibek Bhandari is a freelance journalist based in London.