History testifies to the notion that heroes who die young live longest in the memory. They attain instant immortality, their obituaries acclaimed at the peak of their powers and public profiles in romanticised, nostalgic, era-defining eulogy. They become idols, untainted by failure; legends who defy rather than succumb to the passage of time.

For many motorsport fans the defining moment of the modern era was the tragic death of Ayrton Senna at Imola in 1994. Not only did the sport lose one of its most dashing and daring champions, but Formula One faced a crisis of conscience. In the insatiable pursuit of speed, had safety been lost in the blind spot?

Video: An interview with Bruno Senna

Last Updated: October 11, 2010 UAE

The National caught up with F1's promising young driver, Bruno Senna, for a chat about his expectations for the final 2010 Grand Prix races to be held at Brazil and Abu Dhabi.

___________________

• Outcry as brakes put on Senna film's UAE release

___________________

All of these factors - and more - are dealt with in a new documentary released last week, titled Senna. And to his credit, director Asif Kapadia recognised that a conventional career retrospective could never hope to capture and convey such symbolic subject matter. Instead of mawkish, morbid interviews and reminiscences, Kapadia tells Senna's story through the man himself, in a deeply moving montage of crackly contemporary footage, cockpit cameras and family video that follows his journey from his maiden season in 1984 to his final race a decade later. He skillfully weaves the personal and the public, the podiums and the parties, into a visceral and enthralling story that is closer to a drama than a documentary.

In some ways, Kapadia tells a very personal story, portraying Senna as a man who saw racing in a spiritual rather than a sporting sphere. This is emphasised time and again in the recurring image of the film, lingering close-ups of Senna's piercing, intense, soulful eyes. These images say so much more than a voiceover ever could. Rather than filter his life through the views of others, the audience is given the material and left to make up its mind on the man.

Kapadia utilises that age-old theatrical trick, dramatic irony, to great effect, turning interesting fact into absorbing drama, as everyone knows the tragic ending except the eponymous hero himself. In most films, tension builds as the audience is kept guessing at the outcome. But in Senna, most know the ending all too well and tension comes instead as they scrutinise every frame for clues to whether his death was inevitable or avoidable.

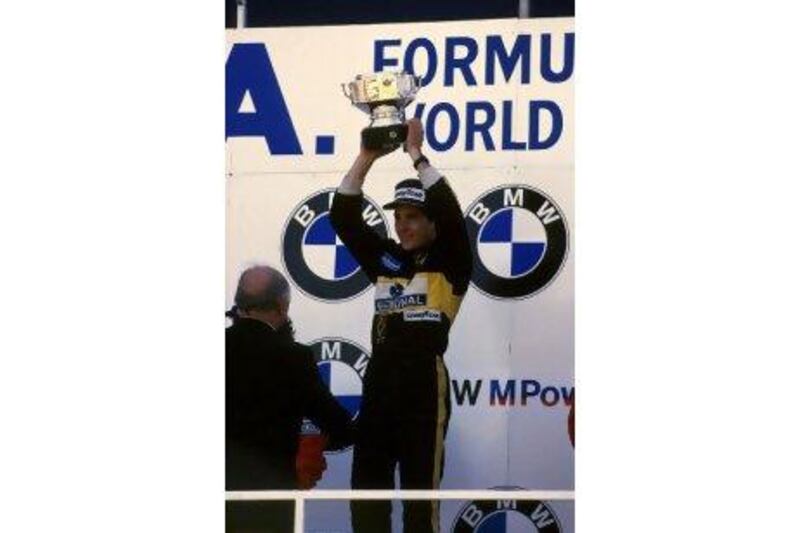

The film sets out its stall from virtually the opening scene. The dashing hero, Senna, battles adversity and the establishment to defeat his nemesis, Alain Prost, to become an idol in his home country of Brazil and an icon to the rest of the world. From his first season with Toleman in 1984, through his switch to Lotus, his maiden Grand Prix victory in Estoril in 1985 and to his first championship with McLaren, the pace is maintained through deft cuts among race commentary, interviews and behind-the-scenes footage. This material is fascinating for Formula One enthusiasts, especially never-before-seen footage from pre-race meetings and garage gossip, but Kapadia succeeds in making it absorbing for a broader audience that may be lost in the detail but is swept along by the drama.

What elevates the film above a dry, technical narrative is the compelling duel between Senna and Prost. His portrayal of the four-time championship-winning Frenchman is less than even-handed and somewhat one-dimensional; he is cast as the pragmatist, cooly calculating a way to prevent the usurper from stealing his crown. But, as with all pantomime villains, he gets many of the film's best lines. Reflecting on Senna's almost maniacal desire to defeat him, he remarks: "He never wanted to beat me; he wanted to humiliate me."

The battle between the two is widely regarded as a key factor in the growth and glamourisation of Formula One, as people were transfixed by their duels on the track and their defamation of each other off it. But Kapadia takes a personal view, revealing how Senna became obsessed with becoming the best, vanquishing Prost and proving that no rules or regulations could prevent his domination of the sport.

Some of the race scenes make for scintillating viewing: Senna's remarkable race in Monaco, 1984, when he came from 13th on the grid to overtake Prost, only to be denied victory by a red flag; the jubilation of his maiden victory at Estoril in 1985 and the infamous culmination of the 1989 season when the cold, calculating Prost barged him off the track to ensure his lead in the championship was unassailable. But this is by no means a mere highlights package. Each scene is carefully selected, with intimate moments building on each race, to tell the story of how Senna's paranoia and almost crazed determination to win saw him reach the pinnacle of his sport.

The level of adoration in which he was held in Brazil is poignantly illustrated in a scene with a young Rubens Barrichello, where, on being introduced to Senna, he is literally rendered speechless in hero worship. The scene where Senna finally wins the Brazilian Grand Prix after many attempts is an awe-inspiring display of human endeavour. Such was his desire to give the home crowd something to cheer that he not only recovered from stalling his car but achieved the theoretically impossible feat of finishing the final laps of the race stuck in sixth gear. So exhausted was he by this super-human effort that he was unable to walk after the race. Overcoming such odds convinced him that it was his destiny to win.

The last quarter of the film focuses on the 1994 season and the moments leading up to his tragic death. After the humiliation of being deprived a drive with Williams in 1993 by a clause in Prost's contract with the team, he finally got his chance to drive the leading car the following year. It is at this point, when the feud between them had become openly hostile, that Prost utters the hauntingly prophetic warning: "Ayrton has a problem. He thinks he can't kill himself." This quote clearly resonated with the director as he briefly steps away from the narrative and muses on Senna's conviction that he was guided in a spiritual quest for perfection, suggesting perhaps that, at the peak of his career, his self- belief was so swelled by success that he considered himself indestructible. This echoes with an earlier quote where Senna admits that, when racing, he sometimes enters a dream-like state "beyond conscious understanding". Did he think he could transcend danger?

Was he destined to die as he was destined to drive?

This intriguing subplot sets up an almost unbearably tense final scene at the Imola Grand Prix. With the Williams car hopelessly unbalanced and uncompetitive, Senna casts a despairing figure in the build-up to the race. Then he is seen strangely detached and aloof after the horrific death of Austrian driver Roland Ratzenberger in qualifying a day earlier. The drivers were forlorn and fatigued by grief, but it was decided that the show must go on.

In a heart-wrenching clip, a Formula One doctor and close friend of Senna, Sid Watkins, tells the Brazilian after qualifying that he has achieved everything in the sport and should retire contented and join him on a fishing trip. Senna declines the invitation. In the next eerie scene, we follow Senna in the cockpit as he leads the field seconds before he careers into a barrier. The audience, though braced for this image, is still left breathless with heads bowed. For some, it would have brought back memories of seeing it live; for others, it would be just the tragic end to a pulsating story.

After Senna's death, a raft of safety reforms were made and, in the 17 years since, no F1 driver has been killed on the track. He was the last; we will never know whether he would have been the greatest. One of the most striking images in the film comes just before the credits roll, and provides a surprising postscript. Senna, the great Brazilian hero and international icon, has a state funeral march in Sao Paolo attended by three million people. And among the melee of screaming mourners is a small, spindly pall-bearer carrying the coffin through the crowds. That man was Alain Prost. Perhaps, after all, it is in rivalry that respect is forged.

Major film distributors in the UAE say there are no plans to screen Senna in the immediate future.