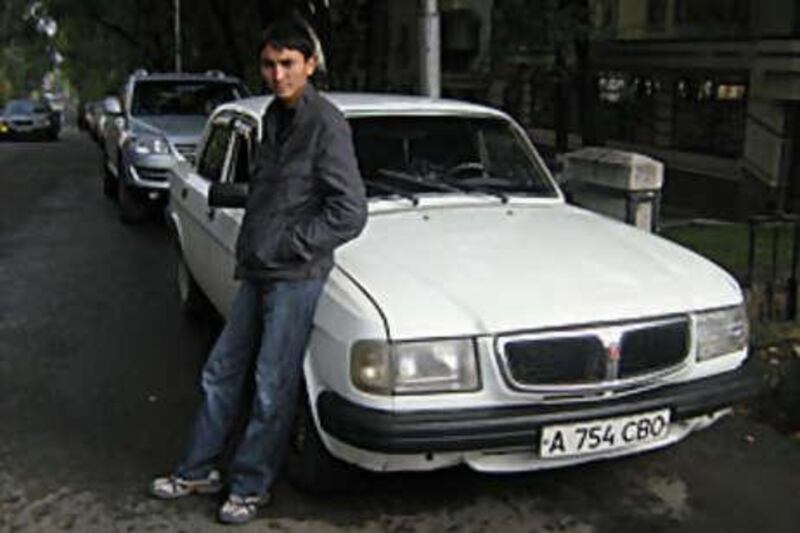

Azamat Sazgascaev drives a second-hand Volga, but he is not a particularly proud owner of what could be described as a dinosaur of Soviet engineering. A university student in Almaty, the largest city in Kazakhstan, 20-year-old Sazgascaev was given the Russian-built car by his father this summer and uses it to travel to classes. "It's comfortable, but it's not sporty and it uses more petrol," he says slightly despairingly, pointing at the fuel gauge which is sitting close to empty.

The reason Sazgascaev drives a Volga is simple: these cars are cheap. Sazgascaev's father paid the equivalent of just Dh9,182 for his son's 1997 Gaz-3110, which has a 2.4-litre engine and the handling finesse of a truck. Even a two-year-old version of the current model, the Gaz-31105, can be picked up for less than Dh 37,000. A modest price, however, has not been enough for the Volga to retain its popularity in the brave new post-Soviet world.

In Kazakhstan, which in 1991 was the last former Soviet republic to declare independence, fewer motorists are driving these heavy, cumbersome motoring relics, which take their name from a river that snakes 3,000km from near the Baltic to the Caspian Sea. While once everyone in the Soviet Union aspired to owning one of these cars - Communist party bigwigs used to travel in them, while those with more modest positions had to make do with Ladas - they are now heavily outnumbered by European and Japanese cars, despite having a soft suspension designed to soak up the bumps on potholed Soviet roads.

The Gaz-31105 can trace its origins back to a car called the Gaz-24, introduced in 1968. Back then, Volgas were comparable in engineering terms with similar-sized vehicles produced by the motoring giants of the United States and Europe. But as carmakers in other parts of the world brought out all-new models every five years or so, Volga manufacturer Gaz Group kept its car in a time warp. There have been improvements in the engine, the suspension and the interior, but the car is fundamentally the same vehicle that was launched 40 years ago.

The giveaway is the shape of the passenger compartment, which has remained virtually unchanged despite tinkering with the front and rear ends. Bulat Yessenkulov, 29, a waiter who lives in Almaty, is one of Kazakhstan's many ex-Volga owners who vows never again to buy a Russian car. Between 1999 and 2002, Yessenkulov drove a Gaz-3110 model. "It's a bad car," he said with a resigned grin. "It's not reliable. All the cars produced in Russia are not good.

"They are not as good as Japanese cars like the Toyota, or European cars like the Mercedes, so they are less popular." Yessenkulov sold his Volga to help finance the purchase of a flat, and when a few years later he was in the market for another car, the Volga was not even on his list of possible purchases. Instead he did what so many other Kazakhs do now, and bought a Japanese car: a dependable Toyota Carina.

"It was nicer and it was easier to drive," said Yessenkulov. "My friends have BMWs and Mercedes and they are much nicer to drive." The cheap price of a new Volga still attracts some buyers, notably taxi drivers in a few Kazakhstan cities, including Semey in the north east where 2007 model Gaz-31105s and older 3110s ferry residents about. But for most private buyers in Kazakhstan, their country's strong political, cultural and linguistic ties to Russia are not enough to make them consider buying a Volga.

It is not that Gaz Group has not tried to update its model range. In the late 1990s it created the Gaz-3105, a modern-looking front-wheel-drive car, but production only numbered in the hundreds. In 2000, the company launched the Gaz-3111, an all-new saloon with a modern shape and interior. Unfortunately, buyers were hard to find and the car was axed after just a few years with production not coming near the 25,000 a year sales figures the Gaz Group had hoped for.

Dana Assanova, 30, a business manager who has lived in Kazakhstan's capital, Astana, for the past five years, remembers the Volga her grandfather owned in the late 1980s. However, neither she nor her friends would consider buying one now. "Twenty years ago, the Volga was one of the best cars, but now in Kazakhstan most people prefer foreign cars," she said. The Volga, she explained, was only thought of as being a good car in the past because during Soviet times, "the choice was so little. Nobody of my acquaintance has a Volga. Russian cars really don't have the quality.

"People think foreign cars are better quality and maybe more prestigious.". The roads of Almaty and Astana are choked with shiny new Japanese and German saloons and SUVs. Where Volgas and Ladas once held sway, now Camrys, Land Cruisers, Pajeros and Mercedes E-Classes sit bumper-to-bumper in traffic jams. In the rural areas and smaller towns new Japanese cars are a rarer sight, although the occasional well-off resident will draw the envious glances of their neighbours with a recent model Mercedes, BMW or even Lexus.

The car of choice in such provincial areas is the second-hand Volkswagen, as these pre-owned cars have been imported en masse from Europe. Probably the most popular model is the Mark 3 Passat, which, while it may be getting on for 20 years old, in engineering terms is a fresh-faced newcomer compared to the Volga. Yevgeny Belousov, a biologist who lives in the south Kazakhstan village of Zhabaghly, drives a Mark 3 Passat diesel estate. Belousov, although of Russian descent himself, has no time for the cars from his homeland.

"You can buy a second-hand car from Europe for $4,000 or $5,000. These are good, reliable cars. The Volga uses too much petrol. It is a Soviet-era car," he says. It is not all bad news for the Volga: in some other former Soviet countries, such as Armenia, the cars have a higher market share and are still used as official limousines. And Gaz Group has taken steps that could bring an upswing in popularity, perhaps even in countries such as Kazakhstan that have become more discerning in their motoring tastes.

In September, the company began production of the Volga Siber, a saloon based on the Chrysler Sebring, after Gaz bought up the model's intellectual property rights. The Siber is one model generation out of date - Chrysler stopped making it in 2006 - but it is light-years ahead of the Gaz-31105. Gaz Group had ambitious plans to produce 100,000 Volga Sibers a year. The credit crunch has, however, had a huge impact on these targets and Gaz Group now predicts its production of cars, including the Siber, could decline by as much as 30 per cent in 2008, compared with 2007.

Similar ambitious plans were outlined when the Gaz-3111 was launched, so the company must hope that its latest move to break into the modern era of car making is more successful than its last attempt. dbardsley@thenational.ae