It's been almost five years since the Roads and Transport Authority introduced Salik, Dubai's first charges for driving on certain routes. Initial problems have now been overcome and congestion in the city has fallen sharply, slashing some journey times.

It is well-documented that people do not react well to change.

So when Dubai's Roads and Transport Authority (RTA) first launched Salik, a road toll system, on July 1 2007, it triggered months of chaos as motorists struggled to adapt to paying to drive on their favourite roads.

However, as the scheme reaches its fifth anniversary on Sunday, ask the average Dubai-resident how they feel about Salik and they will shrug their shoulders as if it has always been part of the city.

"It's something everyone has come to terms with," says Richard Wagner, a Dubai resident and architect at Wanders Architects, who has lived in the emirate since 2005.

"Everyone's got their little tag and there aren't any more questions about it - the gates are almost invisible. And the road system has improved dramatically. If you observe the construction that has gone on over the last two years since the crisis, it was mostly infrastructure; it gave the RTA an opportunity to catch up with the general growth of the city."

Experts estimate Salik - Arabic for "clear" - generates around Dh600 million a year for the RTA based on the assumption there are 1400 cars passing through one lane of a Salik gate during rush hour.

According to a report from the RTA, the system collected Dh800 million from Salik in 2010 while revenue from July 2007 to December 2009 was Dh1.658 billion.

While the RTA say it is not their policy to release revenue statistics, it is clear Salik's inception was never about creating income.

As Mattar Al Tayer, Chairman of the Board and Executive Director of the RTA, pointed out at a press conference soon after the launch: "It does not even generate the cost of one interchange that we build in Dubai."

That does not mean the income goes to waste; the funds are used "to expedite the completion of the infrastructure projects" according an RTA spokesman.

So if revenue was not the driving force for Salik, then the question is, what was?

For those living in Dubai pre-Salik, when the city was at the height of an economic boom, the answer is very simple: to ease congestion.

At the time, a housing shortage and massive economic expansion meant there were far more residents in the city and therefore cars on the roads than the network could cope with.

Anyone wanting to drive from Mall of the Emirates to Deira for an early-evening engagement, had to set aside up to two hours for a journey that now takes 20 minutes.

"The system was introduced to relieve the congestion and direct traffic to other arterials in a way to achieve a system optimal solution of travel time," explains Yasser Hawas, Professor of Transportation and Traffic Engineering at the UAE University.

But Salik was not a gut reaction to a short-term problem. The RTA had first commissioned feasibility studies into a road-toll system in the early part of the last decade as part of a bigger plan to introduce an integrated public transport network to the emirate.

"Dubai knew they were investing heavily in public transport and the Metro was coming. So to get people to do a model shift from using the cars and onto the Metro, you have to impose certain penalties for car use - it's called demand management," says Mehdi Langroudi, an associate transport planner for Ramboll, a global engineering, design and consultancy company with offices in Abu Dhabi and Dubai.

"Once you put in a Salik gate and you have a fee associated with this, for a certain percentage of people it's cheaper for them to use public transport. You get them out of the car and onto metros, buses, taxis and car-sharing."

In Salik's first phase, two gates were installed: one in Al Barsha on Dubai's main artery, Sheikh Zayed Road, and the other on Al Garhoud Bridge, at the time one of the main routes between Dubai and Sharjah.

The tolls had the desired effect, driving motorists off the congested routes. However, because alternatives such as the Metro, a comprehensive bus network and alternative Creek crossings such as Business Bay Bridge weren't complete, it led to chaos.

Previously traffic-free communities became clogged as motorists diverted onto roads unused to such high levels of traffic, to avoid fines or paying the toll.

And because only a small fraction of the city had registered for a Salik tag, outlets were unable to cope with the sudden demand, many running out entirely.

"I got a Salik tag straightaway," recalls Mr Wagner. "I had to take Sheikh Zayed Road to get to work so I had a smooth drive but the surrounding roads were a nightmare.

"It took 10 months for people to realise that when you equate time versus money, it's better to pay those few dirhams; you get there faster rather than waiting in traffic jams."

To compensate motorists, the RTA waived all fines incurred during the first four months of the toll.

Some experts attribute the teething problems to a failure to sufficiently inform the public in the run up to the launch and poor planning.

"It is usual that before going down the road of awarding concessions for the construction of a toll road, the client undertakes various surveys including origin and destination surveys to confirm that once constructed people would want to use it," says Forbes Johnston, director of highways for Mott MacDonald, a global engineering and development consultancy.

"Secondly, there should be a 'Willingness to Pay' survey to establish the base case for toll charges."

However, Professor Hawas, says the initial problems were just a natural reaction to change.

"There is a period of imbalance that usually accompanies the implementation of such systems. It usually occurs when drivers seek other cheaper alternatives to reach their destinations. After a while, these congestion problems dissipate and the flow in the network returns to a state of equilibrium."

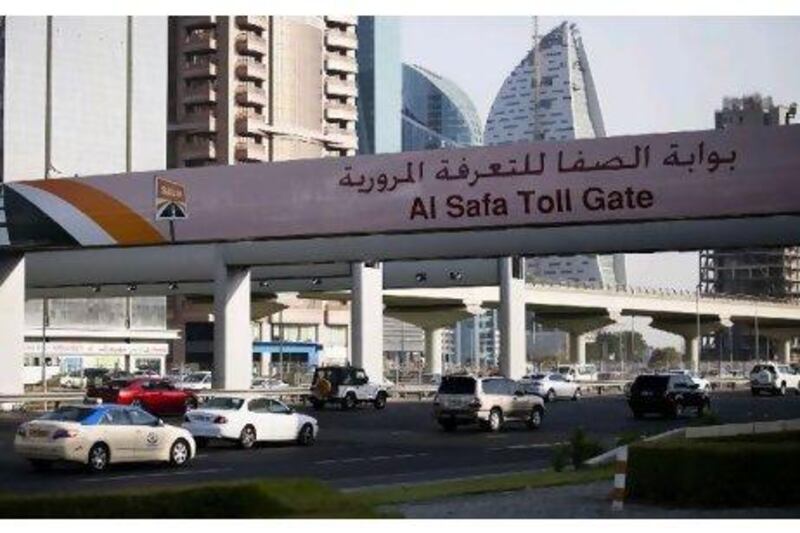

Similar chaos ensued when the RTA expanded the number of tolls from two to four, adding gates at Al Safa Interchange and Al Maktoum Bridge in 2008 to ease bottlenecks that had developed.

But five years on, there is no doubt congestion in the city has reduced, something that has been heavily complemented by the launch of the Metro in September 2009, an improved bus system and a massive investment in the city's road network.

A RTA report from early last year stated that the average speed on Sheikh Zayed Road had increased by 30 per cent in three and a half years, with traffic levels down by 45 per cent on Al Garhoud Bridge and 30 per cent on Al Maktoum Bridge.

But some experts say Salik cannot take full credit for the smoother traffic flow in the city.

"If you think traffic decreased in the city because of Salik, that's not the case. Obviously the economic downfall caused a big reduction in traffic as well in 2009," adds Mr Langroudi.

He worked on the creation of London's congestion-charge programme and was part of the consultancy team that analysed Salik's expansion.

With traffic now flowing so well in the city and almost 350 million passengers using Dubai's public transport in 2011, is Salik still needed?

"The need has reduced slightly but it's picking up again. Dubai is getting busier and if they don't need it now they will need it in five years time," says Mr Langroudi. "Cities in the UAE are not focusing on right now; they have a master plan for five, 10 or even 20 years time and they need all the mechanisms in place now to make sure things stay smooth in the future.

"It's a mechanism that's in place that can be enforced more vigorously if the wish is there."

Though Dubai was the first city in the region to introduce a road toll system, Mr Langroudi says Doha is a likely candidate to follow the Salik model.

Abu Dhabi has also considered a toll system, though Mr Langroudi says the capital would be unlikely to adopt a spot-system like Salik because there are no key routes onto the island, instead opting for a cordon system similar to London's.

"The Service Transport Master Plan for Abu Dhabi looks at congestion charge as a way of doing a model shift to public transport," he said.

"One scenario has been tested to see how much traffic would be shifted to public transport, such as the [planned] Abu Dhabi Metro, by having a congestion charge for vehicles going on to the island."

For now Langroudi says Dubai has succeeding in putting in place a toll system that acts as an example not only regionally but internationally .

"You have to have controls in your own network to be able to shift people around and if you don't have that in place it's very difficult to alter the travel behaviour of the people who are living and working in the country," he said.