I love technology in new cars as much as the next geek but just occasionally I wonder what would happen if it all failed, and whether we have become a bit too clever for our own good in recent years. Rain-sensing wipers, 360° cameras and doors that close themselves are OK; they won't threaten your life if they break down, but how would you react if your fly-by-wire steering, adaptive cruise control, traction or stability control failed when you needed them?

If you're off-roading, and all the electronic wizardry decided to call it a day, would your SUV be competent enough to get you home without a brain box full of computer code?

I was faced with this latter scenario when the soft-roader I was driving left me stranded atop a mountain in Morocco, away from phone reception and civilisation, in the rain and in fading light.

When its ABS, hill descent control, hill start, traction control and the ECU that controls its ability to transfer power between wheels all overheated at the same time and broke down in unison, I quickly realised I was in a land-locked equivalent of being up a stream without a paddle. I effectively had a small, four-cylinder hatchback stranded in a place where only serious 4x4s should venture.

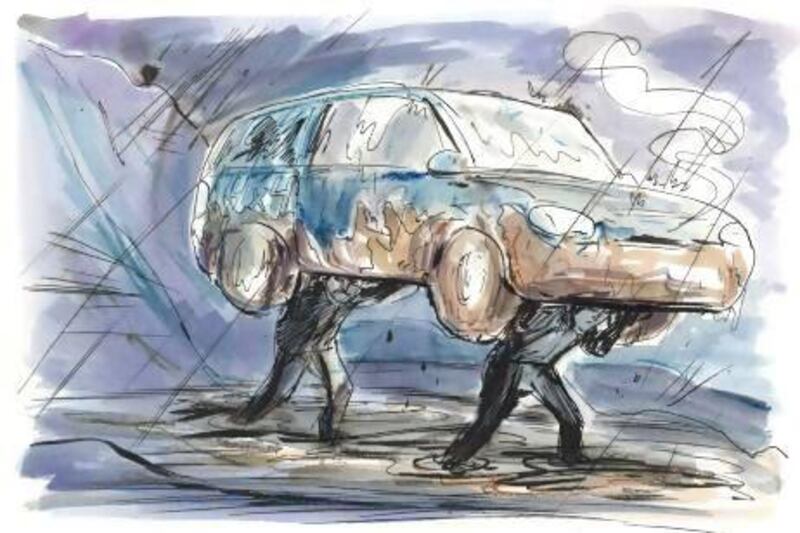

I felt deceived that this shopping car masqueraded as a four-wheel drive, purely through the electronic wonders of its ECU, which controlled where it sent what little power its puny engine developed. Instead of driving all four wheels, like it says on the badge, this new breed of crossover uses computers to transfer power from one wheel to another, effectively robbing Peter to pay Paul and hope that it's enough to get you home.

In full automatic mode, torque distribution is split 50-50 on start up and, if no slip is detected, the onboard computer transfers 100 per cent of its power to the front wheels via a viscous coupling centre diff. As the going gets tough, power is gradually transferred away from the front wheels to the rear and, in the most extreme cases, it will send up to 50 per cent of the torque down the back. Perhaps after our encounter, had more torque been allowed to go to the rear wheels where it was needed, we wouldn't have ended up in as much trouble.

Hill descent control is activated when the descent is greater than 10 degrees and the electronic diff locks are engaged. When this happens, the anti-lock brake system refuses to let the vehicle travel faster than seven kilometres an hour. It's a boon for novices, as it lets the driver take both feet off the pedals and allows the car to drive itself down with computers applying the correct brake pressure. But when it's not there, the road tyres and a lack of engine braking from the wheezy four-cylinder engine gives you no back up plan should it break away and start to slide down the hill.

A hill start is effectively the reverse and works on inclines greater than 10°. Engage first gear, take your foot off the brake and it will hold it without rolling back until the clutch is released.

The three of us in the car knew that, for a soft-roader, we had pushed this car far beyond its engineering brief, brought on by the fast-changing weather mixed with steep inclines and descents on some of the most slippery mud I have ever encountered.

The factory-fitted regular road tyres were hopelessly inadequate to deal with the uniquely sticky mud you find in Morocco and, with every rotation of the wheels, clay wrapped itself around the tyres, adding layer after layer to the point where the rolling diameter filled the wheel arches and our car literally ground to a halt.

With less than six kilometres remaining from more than 60, ploughing through this claylike mud in drizzling rain, climbing slithery tracks and nearly tumbling down a giant ravine, the call came from my co-driver just as we hit level ground on the top of our last hill.

"I think the handbrake's stuck on, she cannae take any more cap'n," my silver-bearded Scottish friend behind the wheel said.

And, with that, our baby 4x4 called it quits, shut down all its electrical traction safety nets and also promptly devoured its own clutch in a steaming mess. Throwing the proverbial hissy fit, it left us abandoned on top of a desolate hill in the rain without tools, phone reception or any signs of life somewhere outside of Fez.

The fact that the sun was soon to drop behind the mountains we'd just traversed meant that we had to face the prospect of camping until daylight returned or hope that a miracle would occur and we'd be moving again soon.

How we got into this mess was a classic piece of poor event organising to start with, as we were on a press launch to test this new model. After our lunch stop when we motored off along the designated route, the track was deemed impassable due to the light rain shower that descended while we were eating. So it was closed, but only after we had started to venture along its slippery path.

With the event organisers unaware that we were on the track, with no radios or communication between the cars, and no recovery vehicles following, we were left to our own devices on how best to get the car running again.

With hindsight, even a basic tool kit would have been handy.

Stranded in a remote corner of the globe, where a donkey and cart (and the goods on it) are still traded as currency, the beauty of an endless view of bald hills laced with grain crops was now punctuated by the pungent aroma of a burnt-out clutch. While the clutch plate stoked its own smoke signals in the vain hope of attracting help from a far-off villager, we got down and dirty, pulling huge clumps of cake-like mud away from the jammed wheel arches with nothing more than a tyre lever and our hands.

After an hour-and-a-half digging mud away from the wheels, the clutch had cooled sufficiently to return enough bite to get us mobile, but with no electronic 4x4 driver aids. The traction and hill descent functions were not keen on rejoining the party, which meant we effectively had a four-cylinder, front-wheel-drive car with no anti-lock brakes, or any devices to control the car in an environment where, in all reality, it should never have been.

With so much mud wedged around the suspension struts suffocating the brake discs, the electronics went into "limp home" mode and, once it had cooled down enough (by which stage we were back on sealed roads thanks to the skills of my co-driver who has decades of off-roading experience), it was back to business as usual.

I like to think that, with many years of driving in virtually every condition imaginable, there's not much that could faze me. But the reality in this situation was that I was dependent on the vehicle to carry me through and, when it failed, if it wasn't for the wily veteran beside me (who forged on ahead, as the tracks were too narrow to turn around, and literally hugged the edges of enormous drops), who knows what the outcome could have been.

The fact we made it through those 60km, in those conditions, was testament to how well electronic wizardry such as hill descent control works in modern off-roaders. The final 6km proved how utterly useless you are should everything not be 100 per cent right.

Before it departed, the traction control light was blinking for more than 90 per cent of the journey, as it strained and struggled to keep everything in control, and strange noises from the over-worked ABS system showed that everything was working madly in what turned out to be a futile attempt to stop our baby 4x4 from turning into an uncontrollable bobsled.

Which brings me back to my original thought. If the car in question had the basics to be considered an off-road vehicle, such as a big enough engine to provide decent compression braking, mechanically lockable diffs and a transfer case - in other words, all the things that make an SUV competent - we wouldn't have had anything to worry about.

Had the conditions been dry and sunny, the track would have been easy but instead, our cold-sweated relief at getting out alive and achieving something everyone - including the company's own engineers who heard our story and inspected our car after we got back to the hotel three hours later - knew the little beast was not designed for, left us more than a little fearful for some of the techno solutions you find in modern crossovers. It also left me with the realisation that there's no substitute for experience behind the wheel.