When one thinks of fashion exhibitions, big blockbusters like Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty; China: Through the Looking Glass; or Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion spring to mind. Large-scale productions, both in terms of narrative and budget, that are brimming with irreplaceable show-stopping dresses, are what we've come to expect from fashion showcases.

What we do not imagine, however, is a show about humble objects like flip-flops, baseball caps or the pencil skirt. Yet these are precisely the pieces about to go on show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as part of an exhibition entitled Items: Is Fashion Modern? As an institution, MoMA has previously chosen to steer clear of fashion, with the only other fashion-themed exhibition during its 87-year history being Are Clothes Modern? in 1944. While it may have taken the museum 73 years to get back on topic, this new foray into the field can be seen as a belated successor.

Running from October 1 to January 28, the exhibition is a look at the small, easily overlooked fashion items that have shaped our world. It is a narrative about how 111 pieces (in both fashion and accessories) have influenced our behaviour, reflected our thinking and changed the way we dress. In the words of MoMA, they are pieces that "had a strong impact on the world in the 20th and 21st centuries – and continue to hold currency today".

Unlike the flashy McQueen or China shows, which present things none of us have seen before, and will probably never see again except in coffee-table books, most of the pieces in Items are familiar, well known, even everyday – but that does not diminish their importance. These are items such as the leather jacket, ballet flats or the Dr Martens boot.

From farther afield, the museum has gathered more diverse elements such as a sari, turbans and a keffiyeh, as it looks to understand the impact these have all had on our lives.

Keen to engage in a conversation about the collection – and not merely present the items as static things in glass boxes – MoMA is inviting designers, manufacturers and engineers to revisit some of the exhibits through new materials, techniques and approaches, and to push the story forward. In the never-ending dialogue about creativity and form versus function, if McQueen: Savage Beauty can be said to have been an adoration of form, then Items is a celebration of function.

In announcing the show, senior curator Paola Antonelli, wrote that as a "powerful form of creative and personal expression that can be approached from multiple angles of study, fashion is unquestionably also a form of design, with its pitch struck in negotiations between form and function, means and goals, automated technologies and craftsmanship, standardisation and customisation, universality and self-expression."

One item in the exhibition that can be credited with leading the charge for self-expression is a pair of button-fly, red selvedge 501 jeans by Levi's. Jeans were first made in 1873 as workmen's trousers – the now distinctive rivet was only added to strengthen the seams – but by the late 1940s, teenagers began to claim ownership of them, primarily as a post-war backlash against strict codes of conduct. That the pair on display at MoMA dates back to 1947 is significant because that was just before jeans became a definitive sign of youthful rebellion, worn by the likes of Marlon Brando in The Wild One (1953) and James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955).

Jeans are, of course, not the only example of reappropriation. Another symbol of the mainstream being absorbed into youth culture is a pair of Adidas Superstar trainers from 1983. First launched in 1969, the low-top shoe with three stripes and a shell-toe design was fairly unremarkable until worn by hip-hop band Run DMC in 1983. Worn with tracksuits, but without laces, this is the first case of sportswear as fashion statement. When Run DMC released the song My Adidas in 1986, it prompted the brand to sign the first-ever endorsement deal between a sports company and a hip-hop band.

One of the most unassuming pieces in the MoMA exhibition is a safety pin. A drearily functional household item, it took on a very different meaning during the punk era in the United Kingdom during the late 1970s.

Quickly adopted as potent symbol, it was pushed through ripped clothes, earlobes and even cheeks by teenagers trying to shock the world around them. Proudly worn as a totem, it set the wearer apart. At the epicentre of this social upheaval were Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren (founder of the band The Sex Pistols), who, reacting to what was going on around them, marked the Queen's Silver Jubilee in 1977 by covering a God Save the Queen T-shirt in safety pins.

The Items: Is Fashion Modern? exhibition notes talk about the show being "driven first and foremost by objects, not designers", adding that "the exhibition considers the many relationships between fashion and functionality, culture, aesthetics, politics, labour, identity, economy, and technology".

In other words, the collection is not about the objects themselves, but what the objects came to signify. And in the case of the safety pin, that small piece of bent metal came to represent the fury and rebellion of late 1970s Britain.

Not everything on show is so contentious. The little black dress (LBD) also features in the MoMA exhibition, with versions by Coco Chanel (1926), Christian Dior (1950) and even Rick Owens (2014). Now an everyday staple, the LBD was unheard of prior to the 1920s, when designers Chanel and Jean Patou both sought to create fashion that every woman could afford. Taking black cloth (which was cheap, practical, but until then solely used for mourning), they turned it into simple, elegant evening wear.

Chanel went one better and mixed it with faux pearls, instantly creating a chic look that has resurfaced many times since (think Audrey Hepburn in the film Breakfast at Tiffany's). So dependable has the LBD become that it spawned a backlash, notably in the 1960s when designer Yves Saint Laurent created Le Smoking, the first tuxedo for women, as an alternative choice for evening wear.

Almost as an aside, Chanel is represented twice in this exhibition, the second instance being the 1924 perfume Chanel N°5, which, with its simple bottle and bold scent, was as groundbreaking as the LBD. At the other end of the spectrum is the Birkin handbag, and while it is fairly safe to say that the vast majority of people do not, and never will, own a Birkin, its inclusion in Items is important because it is the most sought-after bag in the world. On show is the Hermès bag given to Jane Birkin, the woman after whom it was named. Next to that is a Birkin copy by conceptual artist Mary Ping, who copies iconic bags as a commentary on modern consumerism.

Offering a broader perspective, there is also a dashiki (a man's shirt from West Africa) dating back to 1968. Adopted by the Black Panther and Civil Rights movements of the late 1960s in the United States, it was worn as a political awakening, a reclamation of lost African heritage and in protest against social inequality. Back then, it was proudly sported by the likes of Gil Scott-Heron, Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X, but it still resonates today, and has been worn by Beyoncé, Chris Brown and Alicia Keys.

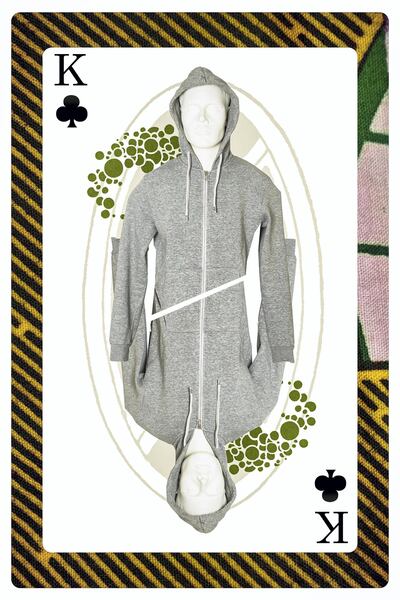

Other exhibits lighter in tone include a miniskirt, flip-flops, red lipstick and moon boots (the winter boots, not the Nasa ones). There are headphones from the 1979 Sony Walkman, and even a hooded sweatshirt by sports company Champion.

There is also a Swatch, the cheap, colourful plastic watch that had consumers queuing around the block in the 1980s. Created to lure back customers lost to Japanese quartz watches, Swatch was launched as a collectable, appealing and overall cheap alternative to a customer's primary watch (which gave rise to its name: Second Watch = Swatch). Costing up to 80 per cent less than traditional Swiss watches, the cheery mix of bright patterns and perceived Swiss quality made it an unexpected must-have.

And that is the common element that extends across the MoMA exhibition. Just like polo shirts, bumbags and espadrilles, Capri pants, burkinis, bikinis and a bandana, every item has been a must-have in its own way. Despite spending a small fortune on forecasting and predictions, it is very hard to gauge what the public will adore and what they will dismiss. Countless dresses, shoes, hats and perfumes have come and gone without so much as a murmur, yet the pieces in this exhibition have all faced the test of consumer whim, and survived to tell their tales.

_______________

Read more:

[ View this spectacular de Grisogono 163.41-carat diamond in Dubai ]

[ Baume & Mercier teams up with regional designers for Fashion Forward Dubai ]

_______________