The Notorious BIG stands in the foreground, a pair of sunglasses shielding his eyes, the twin towers of New York’s World Trade Centre looming behind him. Taken in 1996, a year before the hip-hop legend was murdered, the photograph speaks of a moment in history that can never be repeated.

It is the work of Chi Modu, a photographer for The Source magazine who developed close relationships with some of the biggest names in hip-hop and captured some of the most memorable images of the era – from Tupac, bare-chested and eyes closed, with a stream of cigarette smoke trailing from his mouth, to Eazy-E, leaning against the bonnet of his Chevrolet Impala, and a young Snoop Dogg, peering out soulfully from beneath his hoodie.

The pictures formed part of the first Sotheby’s auction dedicated to hip-hop last month. In 120 lots ranging from a 125th Street subway station platform sign covered in graffiti, to flyers dating back to the late 1970s and clothing worn by some of the genre’s most influential artists, the sale traced the story of hip-hop from its early beginnings.

“The story is that hip-hop is a cultural movement; it’s not just a musical genre,” says Cassandra Hatton, the vice president and senior specialist at Sotheby’s who was responsible for putting the sale together. “It’s a cultural movement that includes music and art and fashion and design. I think a lot of people think of hip-hop as being just music. But it was really a movement that was grassroots, that was built by people in New York, in the community of the Bronx to begin with and then Queens, Brooklyn and Manhattan, and it spread out all over the world. It was built by everyday people who had extraordinary talent and turned it into this massive global cultural force. So that was something that we wanted to show.”

Hatton grew up listening to hip-hop and had been planning the sale for seven years. About two years ago, she was introduced to Monica Lynch, a former president of Tommy Boy Records, which managed the careers of many early hip-hop stars. Together, using word of mouth, they began gathering an unprecedented collection of objects.

“Monica Lynch was instrumental in this, in that she was able to connect me to different people within the hip-hop community, be it musical artists, visual artists, or people who have been working in the industry for decades. It was important to me that all the items spoke with each other – that each had a connection to something else. If you source your material using word of mouth, then naturally the story is formed, because those people know each other and already have a relationship, so those objects will probably have a relationship, too.”

While hip-hop culture certainly doesn’t need institutions such as Sotheby’s to validate it, this sale does mark an interesting turning point. “I think hip-hop has always been big and is important independent of whether places like Sotheby’s have auctions focusing on it, or whether museums like the Met or Moma decide to start collecting art by black artists. It’s already there, in of itself, without any of that happening,” says Hatton.

“But I think that a lot of museums and cultural institutions like Sotheby’s are able to see the value, and are understanding that social currents are changing and that the world is changing. If we want to move forward, we have to be willing to acknowledge that culture isn’t just coming from one place and there isn’t just one tiny group of people that gets to decide what’s valuable.”

The sale also feels particularly poignant in light of movements such as Black Lives Matter, which have been brought to the fore this year. And while Hatton points out that there was nothing strategic in the timing of the sale, she also doesn’t place too much stock in coincidences.

“I am of the generation that grew up listening to hip-hop; hip-hop has influenced my outlook on the world. A lot of the other people who are involved in movements like Black Lives Matter are also of my generation, and also grew up listening to hip-hop. So I think this sale is just part of a larger movement of people who grew up influenced by this, and are able to see the value of black lives and the culture they have spread around the world. I didn’t engineer them to happen at the same time, but global cultural currents coincided,” she explains.

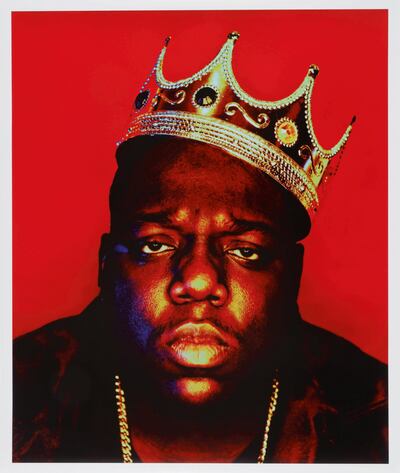

Either way, the auction was a resounding success, generating $2 million, with 91 per cent of all lots sold. Leading the way was the crown worn and signed by The Notorious BIG in the famed King of New York photograph, taken during the artist’s last recorded photo shoot. He was killed in Los Angeles three days later. The crown, which had been in the possession of photographer Barron Claiborne since the day of the shoot, fetched $600,000.

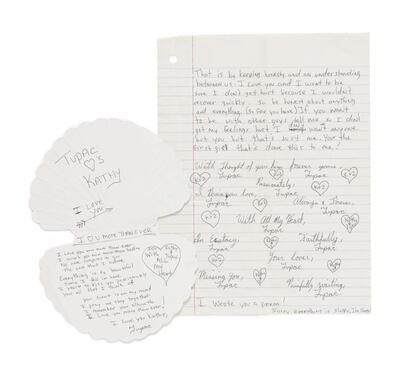

Another star lot was a collection of love letters written by a teenage Tupac to Kathy Loy, a high-school sweetheart and fellow student at the Baltimore School for the Arts. Covering a total of 24 pages, the letters are a testament to Tupac’s naturally poetic writing style, featuring frequent lyrical turns and separate love poems within the body of the letters.

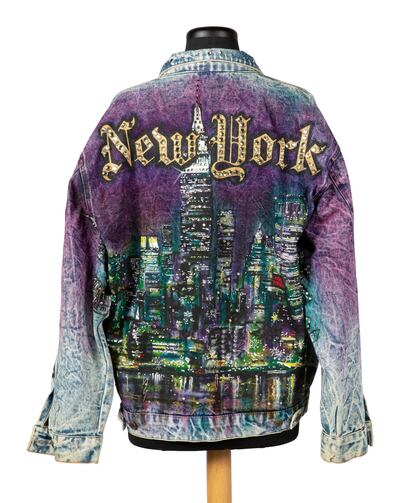

The sale also featured a number of jackets – including a one-of-a-kind prototype Def Jam jacket, Salt-N-Pepa’s personal “Push It” jackets and an original leather Wu-Tang Clan “Parental Advisory” jacket from 1993 – which performed well. “The jackets were pretty exciting,” says Hatton. “We had a lot in the sale and I was little nervous about how many there were, but I think for those, the appeal was they were all historic and vintage, but you can also wear them. That crossover of utilitarianism and art.”

The success of the sale, which Hatton says will be the first of many, is a testament, if needed, to hip-hop’s global appeal, as well as shifting perceptions of what constitutes art. But it is, perhaps most importantly, a mark of the power of music to induce nostalgia. This is something Hatton knows from personal experience.

“Growing up, when I was feeling down and wanted to wallow in it, I would listen to Nirvana. But when things were good and we were celebrating, it was hip-hop. That speaks to the fact that hip-hop is an uplifting music. It makes people feel good and it motivates people.”