When the radical New York designers Marc Jacobs and Stephen Sprouse teamed up with Louis Vuitton in 2000, the anarchic results revolutionised the iconic brand and caused a worldwide sensation. Five years after Sprouse's death, Jacobs talks to Katie Trotter about his latest collection, a homage to his late friend, and his extraordinary career. It was the long and sticky summer of 2000 in Paris. The millennium had firmly planted its opportunistic feet, the 'It-bag' was conceived, and the American designer Marc Jacobs was on a fast train to two very differing destinations - superstar status and rehab. It was also the summer that witnessed one of the most successful collaborations between art and fashion the world had seen since the pairing of Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick. As far as risky collaborations go, the pairing of Marc Jacobs (the big-mouthed fashion titan, and on-off addict) with Stephen Sprouse, the architect of New York punk couture, with the old and rather dusty Parisian fashion house Louis Vuitton, was off the scale.

The somewhat curious partnership had the potential to go blunderingly wrong. But, despite initial rumours of impending disaster, it did not. In fact, quite to the contrary, there began an alliance that would not only reinvent the house of Louis Vuitton and quadruple its sales figures but also secure the name of Jacobs as one of the most pioneering designers of our time. He tells me how he persuaded Yves Carcelle (the chief executive of Louis Vuitton) to get Sprouse on board, and effectively deface the iconic monogram. "I just told him," he says with utter confidence, "that I had been studying the history of the company, and I learned about the tradition of painting clients' initials on the trunks. I wanted to renew this tradition but in a very modern way: with graffiti. For me, the king of graffiti was Stephen Sprouse, so what did he think if we collaborated and printed his graffiti on our traditional bags? He liked the idea. He found it very modern. And the public liked it too."

I first came across Marc Jacobs while working as an intern for Alexander McQueen, and with the confidence of youth managed to talk my way into the Jacobs Spring/Summer 2004 show. My lasting impression was not of the beautiful clothes, nor the buzz of my first fashion show but of a desperately awkward-looking character peeping around the curtain to take his final bow. This was not how I expected a superstar to look. Bespectacled and slightly chubby, with unkempt flyaway hair, he reminded me of Tim Burton. He was unpolished, his squinty smile and darting eyes oozed discomfort, and I instantly liked him.

Jacobs is notoriously blasé about his fame and talks about his shortcomings and insecurities with the ease of someone who has undergone a lot of therapy. I begin to wonder if this fragility is key to the Marc Jacobs brand, the thing that draws us in and keeps us riveted. "I'm just a person who enjoys doing what he does and I don't mean that in a falsely modest way. As far as how I am perceived - awkward, yeah, I'm awkward and I'm insecure and I'm uncomfortable. But, at the same time, I also have days of confidence and security."

Jacobs has a charming vulnerability, almost that of a lost child, which of course he was. His father died when Jacobs was just seven and there followed a string of unsuitable suitors and marriages for his somewhat absentee mother. After she moved away permanently, Jacobs was taken in by his paternal grandmother, the only member of his family he speaks about with any real emotion. "She always encouraged me in everything I did," he says. "I wouldn't say that her influence was determining but she was a woman who had a lot of class and an innate sense of fashion."

After having made a few attempts at launching his own label and a troublesome period as creative director at Perry Ellis, it wasn't until Louis Vuitton appointed him artistic director in 1997 that Jacobs was given the creative freedom and financial backing he craved. It was a plucky choice: here was a century-old, rather staid fashion house handing over its luxury fashion brand to a New York club kid. How would Jacobs begin to understand the essence of the Vuitton woman?

The way he tells it, it was really quite simple: "The Vuitton woman is looking to underline her status through the clothes she wears; she wants people to know what she is wearing, it has more to do with psychology than a fashion statement, the brand is a true icon, and its important that it is recognised immediately." Jacobs was making steady progress at Vuitton, but felt he needed to make his mark on the brand in order for it to evolve. "I respected the world of Louis Vuitton, but I wanted to bring it to a parallel world that honoured the past but was open to the present."

The idea of teaming up with Steven Sprouse came when Jacobs was staying with his friend Charlotte Gainsbourg in Paris in the late Nineties. "In her bedroom, she had a Louis Vuitton trunk painted black by her father [the singer] Serge, and some of the paint had peeled off to reveal the monogram. I thought it was very cool, particularly the idea of taking something iconic and venerable and giving it a new meaning by actually destroying or defacing it. I wanted to do this with graffiti, which to me has always been a defiant, anarchic act, but also something that creates a new surface and meaning with something old."

There was no question whom he would look to in order to realise his vision. He wanted, and needed Stephen Sprouse, a designer whose signature Day-Glo colours and distinctive graffiti-prints had redefined New York streetwear. "I thought about whose hand would mean something to me, and of course I went back to Stephen, who I knew would find a new way of promoting Louis Vuitton with his fabulous graffiti in a way that was both disrespectful and respectful at the same time."

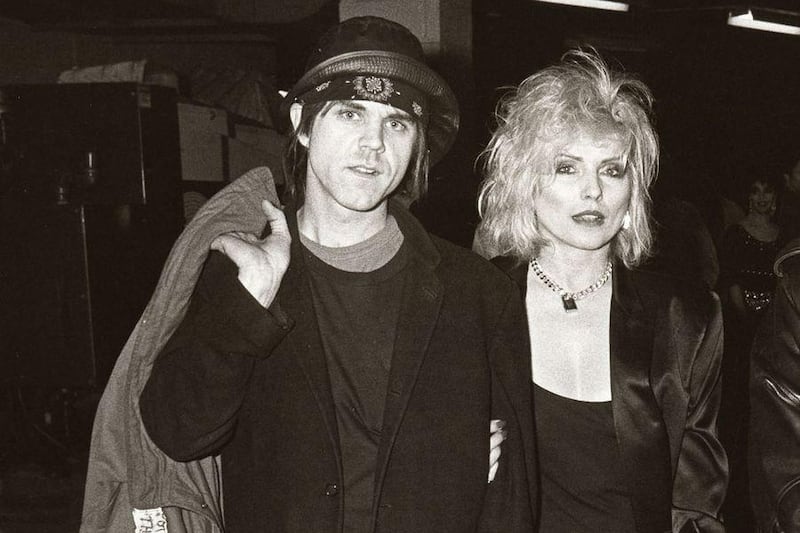

Sprouse was, in a way, everything Vuitton was not, and the first designer to mix fashion, rock and art. A key figure in the underground music and arts scene, he worked with the likes of Andy Warhol, Debbie Harry and Guns N'Roses, and developed a drug habit to prove it. He was the perfect mix of uptown skill and class and downtown pop sensibility, and he was the perfect candidate to shake the Louis Vuitton boat.

Sprouse was uncomfortable with the fashion industry and its commercial constraints. Despite the backing of fashion editors, such as Vogue's Anna Wintour, and the right kind of celebrity profile, he was never successful in business. He needed Jacobs as much as Jacobs needed him. Jacobs had known Sprouse from the New York clubbing scene and had long been a fan. "It had always been a dream of mine to work with Stephen, and I am someone who never abandons his dream," he smiles.

He remembers the time he spent with Sprouse fondly. "When I had started to design, he was already one of the young New York artists who had a very affirmative vision of fashion, he was a designer and a person for whom I had a profound respect." For six months during 2000, Sprouse and Jacobs worked together in Paris for Louis Vuitton's Spring/Summer 2001 collection. When it was launched, the collection was an instant sell-out, with waiting lists so long that Sprouse himself complained he couldn't get his hands on his bag of choice.

But there was to be no second collaboration. Sprouse died in 2004, aged 50, and the new collection pays homage to him. "I have done my best to do what I think Stephen would have done," says Jacobs. "I took very basic pieces, like the balmacaan [a style of overcoat] that he always loved, and put the Louis Vuitton monogram inside, and his graffiti over it. Or I made a little T-shirt dress with a singular engineered print in fluorescent colours.

"I tried to use the things in Stephen's vocabulary, and give the collection the shape, silhouette and styling that Stephen would have done when he was at the top of his game." And Jacobs' favourite piece from the new collection?" I would say the fluorescent pink graffiti leggings." As is the case with many creative innovators, there is a lack of contentment surrounding Jacobs, a deep sense of unease and a constant longing for fulfilment. He is a perfectionist, and perfectionists are often addicts. I wonder if his well-documented struggles with substance abuse are an easy way to numb his insatiable curiosity. Addiction is something he does particularly well. Brilliantly, actually, and his early tenure at Louis Vuitton was legendarily rocky, as Jacobs himself confirms.

"When I first went into rehab in 2000, I had a really horrible problem, I was a daily drug and alcohol user and I went into rehab against my will. I had no choice - it was [my business partner] Robert Duffy who kind of saved my life." He has recently undergone a complete physical overhaul and is so fit and toned, he now resembles a honey-skinned GI Joe. I wonder if this is just another form of addiction, although he swears the only one left is his love of Marlboro Lights (albeit three packs a day).

Has he learned to disguise his sensitivities? "I don't really care," he replies. "I am very outspoken and honest. I don't really hide things with the fear that they are going to be revealed on blogs and in magazines, I prefer to be myself and work in a positive way doing what I like." The future doesn't interest Jacobs. In fact, talking about it is the first time I sense he is genuinely uncomfortable. I wonder (although he disagrees), if there is little part of a Peter Pan syndrome there.

"It's not an age thing. I just want to think about the present - the present shows us where we are, which is the most beautiful place to be," he says. "I don't ever want to feel I have gone far enough, or that I have come so far that it is my turn to be looked up to. I just don't want to be there." Jacobs may be stubborn and unpredictable but his protestations of self-doubt have a ring of truth. Unlike many of his contemporaries he is under no pretence or illusions about the eccentric world he inhabits, and approaches fashion with a healthy irreverence.

"They are just clothes," he says. "I want people to love them, to enjoy them and to realise they are nothing more than that. And anyway clothes without a life to live them in are just nothing."