Artek's furniture designs continue to impress - as working pieces and as works of art. While its classic past is on display in museums worldwide and at the new Archive in Dubai, the company's CEO says it must still take risks, writes Selina Denman

When Finnish architect Alvar Aalto came to design the Paimio Sanatorium for tuberculosis sufferers in 1928, he paid special attention to the floors. He imagined that the sanitarium's sick, vulnerable patients would spend a lot of time staring at the floor, and wanted to ensure that they had something pleasing to look at. He also introduced pigeonholes where patients could store their slippers, a tiny detail intended to create a sense of homeliness, and large balconies where patients could bask in the sun and get plenty of fresh air - the best-known treatment for tuberculosis at the time. And he placed his Chair 41 in the sanitarium's public spaces.

The Aalto 41 is now a design classic, lauded for its simple, lightweight, sculptural beauty and structural ingenuity, and has been displayed in museums around the world, including New York's Museum of Modern Art - but at the time, Aalto's main priority was creating a piece of furniture that was comfortable, hygienic and would help prevent the spread of bacteria.

Aalto went on to design a number of iconic buildings, at home and abroad, including the Viipuri Library, several buildings for the Helsinki University of Technology, the Finlandia Hall, the Essen Opera House and the Kunsten Museum of Modern Art. In 1935, he and his wife Aino Aalto joined forces with two liked-minded idealists, Nils-Gustav Hahl and Marie Gullichsen, to launch the furniture company Artek, "to promote a modern culture of habitation".

But, despite being one of his earliest works, Paimio still stands as a prime example of Aalto's holistic, human-centric approach to design. "Paimio is a holistic architectural creation; it connected Aalto's ideas of how nature has a connection to architecture, how an interior is connected to the building itself, and how furniture has a connection to architecture and to nature and, more than anything, to the human being," says Mirkku Kullberg, the current CEO of Artek. "Aalto was a forefather of the international modernist movement, in a very Nordic, Scandinavian way," she adds.

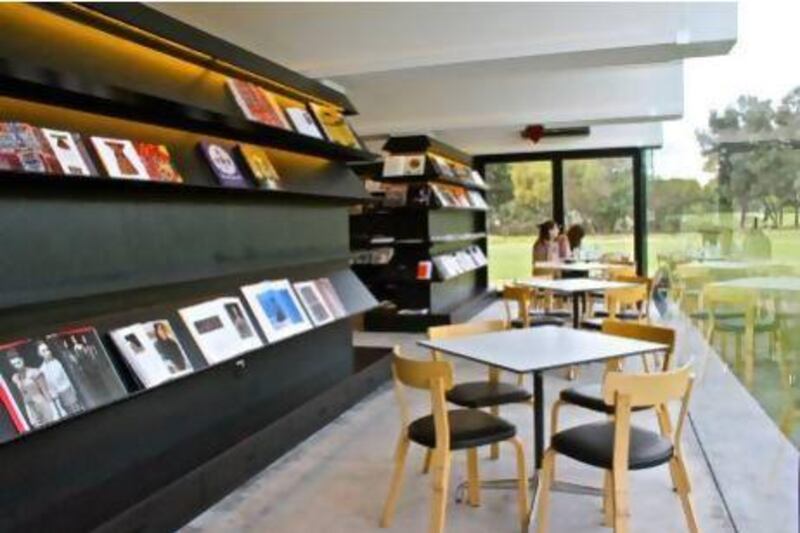

Artek's back catalogue is filled with pieces that helped define the Scandinavian design aesthetic that is still so popular today, from the 80-year-old Stool 60 to the Mademoiselle Lounge Chair and the Chair 69, which can now be seen in the recently opened Archive in Dubai's Safa Park. Aalto essentially took an undervalued raw material, Finnish birch, and made it ultra desirable.

Nearly eight decades after Artek was launched, Aalto's legacy is a source of great pride for the company - but it can also be an obstacle, says Kullberg. "Frankly, the company was very stagnated when I joined in 2005. It's important and interesting to have a legacy but it can, in turn, be a burden.

"It's very much linked to a fear of making mistakes. If you have a company that is almost an institution, with heroes like Alvar Aalto and the other founders, you almost don't dare to move the company forward. Instead you start protecting the legacy, and it becomes like a museum. But if you don't take risks you can't push the organisation into those uncomfortable zones where you start creating new things."

Before joining Artek, Kullberg spent 20 years in the fashion industry, specialising in the turnaround of small- to medium-sized companies that had become "prisoners to the old way" of doing things. "I think there is always something genuinely interesting if you have an old company that has been around for 50 years or 70 years and it still exists. My job is to go back and find the original identity or ideology and work out how to move forward. At Artek, we had to change the maturity of the people and bring a new energy in, while at the same time trying to retain all that old knowledge.

"What we now do particularly well is we combine that old legacy with new product development. We have been launching some new things through the Artek Studio and next year we will be launching quite an amazing new collection, but everything follows the same old basic rules. And we still have a very strong connection to culture and art."

Kullberg left the fashion industry after becoming frustrated with its obsession with "the new" and "the latest". When she joined the industry, fashion houses would launch two to four collections a year; by the time she left, there was something new being launched every other week, she says. And in an era where people are constantly being bombarded with new products, an overload of information, non-stop Facebook updates and relentless advertising, "finally the consumer starts thinking 'it's too much' and starts filtering the things that they really respect and which they really believe in", she says. This is when companies like Artek, which have history and a proven track record of providing quality products that can stand the test of time, really come into their own.

Like fashion, the design industry is not immune to a preoccupation with "the new", says Kullberg, who prefers to take a longer-term approach to product development and launches, and is far more interested in "phenomena" than trends. In her characteristically upfront fashion - not a particularly common trait in someone working in either the fashion or design industries - she refers to the recently held Milan Furniture Fair.

"I hate those fairs. There are so many products that are there only for the fair; that are only prototypes. They are created for the purpose of newness and for the press. Basically, I think it would be better if launches did not happen so frequently - maybe every third year or so.

"When you launch a product, it takes time before the consumer adapts to it. I don't think you can do it in less than three years. That's how long it takes for a product to prove itself."

Kullberg is no fan of the word "sustainability" but only because of the way that the term has been abused in recent years. "Yes, you are using sustainable raw materials; yes your processes are sustainable and your electricity is controlled. So? I think it's a much bigger issue and the only way of really talking about sustainability is by extending the life cycle of the product. That's real sustainability."

Buy a product from Artek and, chances are, your box will be covered with the slogan, "One chair is enough", "Buy now, keep forever" and "Timeless content inside". But surely it is not in the interests of any profit-orientated business to encourage its customers to buy one chair and keep it forever, I suggest. "The design industry doesn't exist without business itself and has to be result-driven like every other business. But if everybody improved their way of acting by 20 per cent, we would be a much healthier industry," Kullberg counters.

Artek's Second Cycle project proves that Kullberg's commitment to sustainability is not your usual posturing. Since Artek was founded in 1935, the company has sold some eight million Aalto stools. A few years ago, it started gathering back old, unwanted stools and chairs from flea markets, schools, old people's homes and garages, to give these classics a new lease on life. Full of character, knicks and other signs of a life well lived, these stools are now on sale.

"Nothing old is ever reborn but neither does it totally disappear. And that which has once been born will always reappear in a new form," Aalto once said. And this is one part of his legacy that Kullberg seems entirely committed to keeping alive.

Follow us

[ @LifeNationalUAE ]

Follow us on

[ Facebook ]

for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.